Warren Buffett Accounting Book

Stig Brodersen

GENRE: Business & Finance

GENRE: Business & Finance

PAGES: 256

PAGES: 256

COMPLETED: August 31, 2022

COMPLETED: August 31, 2022

RATING:

RATING:

Short Summary

Stig Brodersen takes readers through a line-by-line exploration of a company’s key financial statements — the income statement, the balance sheet, and the cash flow statement. The Warren Buffett Accounting Book breaks difficult accounting concepts into easy-to-understand language using insight from Warren Buffett’s teachings.

Key Takeaways

Favorite Quote

“It is extremely important to find a company that demonstrates a consistent earnings capacity, book value, and a stable and respectable ROE over numerous years, not just a few.”

Book Notes

Ch. 1: How to Look at the Stock Market

- Stocks = Ownership — When you buy stock in a company, you essentially own a piece of the company. You get to participate in the company’s profits. For that reason, and many others, it’s important to analyze the company before buying shares.

- Price & Value — The price of a stock differs quite a bit from its real value. Day-to-day movements in a stock’s price are driven by supply and demand and a ton of random factors. Short-term price movement is largely driven by human psychology. Evaluating the value of a stock involves fundamental analysis of the company itself.

- Bubbles — Bubbles occur when the price of an asset has risen disproportionately high in relation to its true value. More and more people buy the asset and drive up the price. Fear of missing out (FOMO) kicks in and eventually the price of the asset is way too high. The bubble eventually pops and people lose a lot of money.

- Ex. Dot-com Bubble — In the late 1990s, technology and internet stocks became a bubble. People couldn’t stop buying these stocks. Eventually the bubble popped and these stocks crashed in 2000. Millions of dollars were lost.

- Bubbles — Bubbles occur when the price of an asset has risen disproportionately high in relation to its true value. More and more people buy the asset and drive up the price. Fear of missing out (FOMO) kicks in and eventually the price of the asset is way too high. The bubble eventually pops and people lose a lot of money.

- Market Drops — When the market drops and stock prices fall, it’s the equivalent of items in a store going on sale. Just as you would in a store, that’s the time to take advantage and buy good deals. Market declines should be looked at as a good thing, especially if you have a long time horizon ahead. Buy great companies at discounted prices and enjoy the ride up. The only time a market drop is bad if if you need your money soon and/or are nearing retirement and have a short time horizon.

- Quote (P. 10): “As a stock investor, you should almost always hope for the market to drop.”

- Eliminate Time — The concept of time is what gets a lot of people in trouble with investing. Your focus shouldn’t be on buying and selling stocks frequently and trying to “time” the market to make a quick profit. Your focus should instead be on analyzing companies, buying good companies, and holding them forever. When you do this, you take much of the emotion out of investing and reduce any impulse to make a rash decision.

Ch. 2: Concepts Every Investor Should Know

- Interest Rates — Interest rates have a big impact on companies, the stock market, and the real estate market. Interest rates are a big X-factor that always need to be watched closely. The Federal Reserve (FED) controls interest rates in the market.

- Companies — When interest rates rise, business becomes more difficult. The cost of debt goes up because companies have to pay more in interest when they borrow, which has a direct negative impact the income statement and earnings. The opposite is also true — when interest rates are low, companies have an easier time doing business because they can borrow money at cheaper rates and pay less interest, which helps the income statement and boosts earnings. And earnings drive stock price movement.

- Bonds — When interest rates rise, the interest payments on new bonds go up. Bonds are generally safer than stocks, so many people will pull their money from the stock market and instead put it into bonds, which have less risk. By pulling their money out of the stock market to place it in the bond market, people drive the price of stocks down. In this way, interest rates can have a big impact on the stock market.

- Real Estate — When interest rates are low, people are able to borrow money at cheaper rates. A person can get a 30-year mortgage and pay less in interest on the loan when interest rates are low. This type of interest rate environment encourages more people to take out a loan and buy a house. With more people in the market for a house, demand rises and house prices respond by also rising. The opposite is also true — when interest rates are high, it’s more expensive to get a 30-year mortgage because your interest payments are going to be higher. This discourages people from taking out a loan, which reduces demand for housing. House prices respond by falling.

- Quote (P. 20): “(Interest Rates) are truly the foundation to the entire economic cycle and value of everything on the planet.”

- Federal Reserve (FED) — Independent organization that manages the money supply and fiscal policy for the United States Government. One of the FED’s most important jobs is influencing interest rates. The FED manipulates interest rates to boost or slow the economy.

- Hot Economy — When the economy is hot and inflation is high, the FED raises interest rates to discourage spending and consumption, which stabilizes prices and prevents bubbles.

- Cold Economy — When the economy is down, the FED lowers interest rates to encourage spending and consumption, which will lead to more employment and greater wealth. For companies, lower interest rates will encourage borrowing for new projects, which again leads to greater employment and wealth in the economy.

- Inflation — The FED controls the money supply and prints more and more money. Prices of goods and services go up over time because there are more dollars in the economy. Inflation means the value of your money decreases over time — $1 in 1913 was worth $23.49 in 2013.

- Nominal Dollars — Nominal dollars do not account for inflation.

- Real Dollars — Real dollars account for inflation.

- Inflation & Investing — As an investor, inflation eats into your returns. If you make a 10% nominal return on your stocks one year, but inflation was 2%, you made an 8% real return. Over time, that adds up significantly and really eats into your returns. But there isn’t anything you can really do about it because inflation impacts all investments.

- Bonds — Essentially a loan. You are lending money to the government agency or company and will be paid interest quarterly. Interest rates and bond prices have an inverse relationship — when interest rates rise, bond prices go down because nobody wants to pay the same par value price for a bond that is paying less interest than brand-new bonds with the higher interest rate. Inflation is pretty killer to bonds, especially long-term bonds. There are three main components of a bond:

- Par Value — This is the amount the bond is issued for. This is normally $1,000. You get this amount back when the bond matures.

- Term — The duration of the bond until natures.

- Coupon/Interest Rate — The interest the organization is paying you for lending them money. Shady companies have to pay more in interest to compensate the investor for taking on additional risk. This is why junk bonds have much higher interest rates than the bonds of a AAA-rated company.

- Ex. Long-Term Bond — You invest in a 30-year $1,000 bond with a 5% coupon. You will receive $50 every year in interest payments and you’ll get your $1,000 back at the end of the 30 years.

Ch. 3: A Brief Introduction to Financial Statements

- Financial Statements — All publicly traded companies are required by the SEC to file a 10K (annual) and 10Q (quarterly) report. These reports detail background information about the company, financial information, and more. The income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement are the key financial documents to analyze.

- Income Statement — One of three key financial statements that a company puts out quarterly and annually. The income statement reveals the net profit (or loss) that a company had over a period of time (normally a year in the 10k report). The top of the statement shows revenue/sales for the period, and subtracts various expenses and taxes until earnings are shown at the bottom. Earnings Per Share (EPS) is found by dividing net income by the number of shares outstanding.

- Personal Finances — The income statement for a company is similar to that of a person’s personal income statement. A personal income statement would start with salary at the top (essentially revenue) and subtract various personal expenses (like housing, food, gas, clothes, etc.) until profit/loss for the period (earnings) are displayed at the bottom.

- Balance Sheet — A snapshot of a company’s financial health on a certain day (usually December 31). This document essentially shows you how much the company is worth on that day. The balance sheet reveals a company’s total assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity and must always balance. You subtract liabilities from assets to find shareholders’ equity. It will always balance because shareholders’ equity is technically not owed to the company — it is money owed to shareholders and is therefore considered a liability.

- Formula — Assets = Liabilities + Shareholders’ Equity.

- Personal Finance — A company’s balance sheet is similar to a personal balance sheet. A personal balance sheet will include assets like your house, car, furniture, clothes, etc. It will also include liabilities like your mortgage, car payment, student loans, credit card debt, etc. In the end, you subtract assets from liabilities to find your net worth (shareholders’ equity).

- Book Value — Book value summarizes a company’s shareholders’ equity. To get book value, you divide equity by the number of shares outstanding. This number gives you a look at company’s total equity on a per share basis.

- Cash Flow Statement — The cash flow statement measures how much cash is moving in and out of the company. The company can therefore always track how much cash it has and avoid the unfortunate situation where it has no cash to pay creditors, employees, or any other third party.

- Quote (P. 36): “At first glance, the income statement and cash flow statement might seem very similar. In many ways, they are. But the key difference is the income statement is capturing the profit of the business over time, and the cash flow statement is looking at the changes in cash over time.”

Ch. 4: The Principles and Rules of Value Investing

- Buffett’s Rules — Throughout his career, Warren Buffett has generally followed four core investing principles:

- Vigilant Leadership — You want to invest in companies with a leadership team that is making good decisions and maximizing value for shareholders, rather than putting money in their own pockets. A well-managed company typically has the following qualities:

- Low Debt — Try to avoid companies with a lot of debt on the balance sheet. The Debt/Equity Ratio allows you to easily evaluate a company’s debt position. Divide a company’s total liabilities by its total equity to get this ratio.

- Ex. $250,000 in liabilities and $100,000 in equity ($250k / $100k = 2.5 D/E). This means the company has 2.5 times more debt than equity.

- High Current Ratio — Current assets are assets expected to be turned into cash in the next year or sooner. Current liabilities are obligations that must be paid on the next year or sooner. The current ratio (Current Assets / Current Liabilities) shows how quickly a company can pay off its short-term responsibilities. The higher the ratio, the more current assets the company has and the quicker it can make payments.

- Strong/Consistent Return on Equity — Return on Equity (Net Income/Shareholders’ Equity) reveals how well the leadership team is making decisions. A high ROE indicates that the company is using its cash efficiently and investing in strong projects. An ROE of at least 8% is good, but look at the long-term trend rather than just one year.

- Quote (P. 49): “The ROE is extremely important because it demonstrates the effectiveness of management’s ability to reinvest your profits in the business. Considering most companies retain most of the profits and reinvest the money for you, you’ll probably find the ROE one of the most important figures for assessing the performance of your stock.”

- Appropriate Management Incentives — You want to invest in companies with managers who are incentivized by long-term goals, not the short-term performance of their stock. Make sure the company’s leadership team is incentivized to help the company and its shareholders rather than themselves.

- Low Debt — Try to avoid companies with a lot of debt on the balance sheet. The Debt/Equity Ratio allows you to easily evaluate a company’s debt position. Divide a company’s total liabilities by its total equity to get this ratio.

- Long-Term Prospects — Long-Term prospects come down to two components:

- Persistent Products — The company’s products should be able to survive anything. You don’t want to invest in companies that offer products that could be outdated and a matter of years. Coke is a good example of a company with a durable product.

- Minimize Taxes — Taxes are the single greatest expense for every person. When you hold your shares for over one year, you can minimize your tax burden by selling at the capital gains rate (15%) rather than your ordinary income tax rate.

- Stock Stability — You want to invest in companies that are stable and hav e proven to be stable over a long period of time. Look into two areas here:

- Stable Book Value & Earnings — You want to see stable and steady growth in book value (shareholders equity/shares outstanding) and earnings per share. EPS in particular really drives stock prices. Look for a trend, not just one year.

- Quote (P. 67): “It is extremely important to find a company that demonstrates a consistent earnings capacity, book value, and a stable and respectable ROE over numerous years, not just a few.”

- Takeaway — Look at trends in a company’s EPS, book value per share, and ROE. These are a good place to start when analyzing a company.

- Quote (P. 67): “It is extremely important to find a company that demonstrates a consistent earnings capacity, book value, and a stable and respectable ROE over numerous years, not just a few.”

- Competitive Advantage — A company with a competitive advantage is difficult to penetrate. These are the companies you want to invest in because they have a big leg up on everybody else. Branding (i.e. Coke) and low costs (i.e. Walmart) are examples of ways a company can have a competitive advantage.

- Stable Book Value & Earnings — You want to see stable and steady growth in book value (shareholders equity/shares outstanding) and earnings per share. EPS in particular really drives stock prices. Look for a trend, not just one year.

- Attractive Prices — There are a few things to evaluate when trying to decide if a stock’s price is attractive. These include:

- Margin of Safety — The intrinsic value of a company is what you’re trying to find out by reading financial statements. The market price of the stock is whatever the market says it is. The margin of safety is the difference between the two. You want to establish a decent margin of safety when doing your analysis because it will give you some wiggle room if your evaluation of intrinsic value is off.

- Low P/E Ratio — P/E = Market Price/EPS. This multiple gives you a quick read as to whether the stock is overpriced or underpriced in the market compared to other companies in the same industry. It tells you: “This stock is trading at XX times earnings.” It can also be thought of as: “For every $1 of the company’s earnings, I am paying $XX.” This ratio should be thought of with the future in mind. When a company has a high P/E ratio, it means that investors are willing to pay a high market price (for low earnings right now) in order to get in on the stock early with the expectation that earnings will grow significantly in the future and “catch up” to the market price. A high P/E usually means the company is being overvalued by investors. A low P/E signals that the stock is undervalued.

- Low Price-Book Ratio — PB Ratio = Market Price / Book Value Per Share. The price-book ratio tells you how much you are paying for every $1 of the company’s equity. A price-book ratio of 12 means you’re paying $12 for every $1 of the company’s equity (assets-liabilities). The lower the better.

- Vigilant Leadership — You want to invest in companies with a leadership team that is making good decisions and maximizing value for shareholders, rather than putting money in their own pockets. A well-managed company typically has the following qualities:

Ch. 5: Financial Statements and the Stock Investor

- Financial Statements — Annual and quarterly financial statements and conference calls give you great insight into a company and its future prospects. It’s critical to have a basic understanding of accounting so you can read and understand the financial statements.

- Quote (P. 123): “Accounting is the language of business.” — Warren Buffett

- Debits & Credits — In accounting, every move has an implication. The accounting system is built on double entries. Every debit in one account is accompanied by a credit to a different account. When moves are made, money flows to and through other accounts. Although you don’t really need to understand debits and credits, the big point to remember is that the money is moving to other accounts and your goal as an investor is to figure out where and why it is moving.

- Quote (P. 129): “The important point is this: If money listed on a financial statement is bigger or smaller from one reporting period to the next, we know the money went somewhere. The investigation into where the money went is the part that makes you a smart and successful investor.”

- Takeaway — If a company’s cash position, for example, went up significantly between reporting periods, you need to look at the financial statements and figure out why that happened. Where did it come from? A loan? Net income?

- Quote (P. 129): “The important point is this: If money listed on a financial statement is bigger or smaller from one reporting period to the next, we know the money went somewhere. The investigation into where the money went is the part that makes you a smart and successful investor.”

- Cash Accounting — Transactions are only recorded at the time when actual cash has exchanged hands. This type of accounting is essentially how we all operate in our daily lives.

- Ex. Starbucks — When you buy a cup of coffee at Starbucks, you trade cash for coffee and the transaction would be recorded right there.

- Accrual Accounting — All publicly traded companies must use this form of accounting. Transactions are recorded at the time of the agreement, even if actual payment will not be received until a future date.

- Ex. Starbucks — If Starbucks received an order for coffee beans from another business, the transaction would be recorded at the time of the agreement. The other business may not actually pay for the coffee beans for another 90 days, but the payment would be recorded at the time of the agreement.

Ch. 5: Financial Statements and the Stock Investor

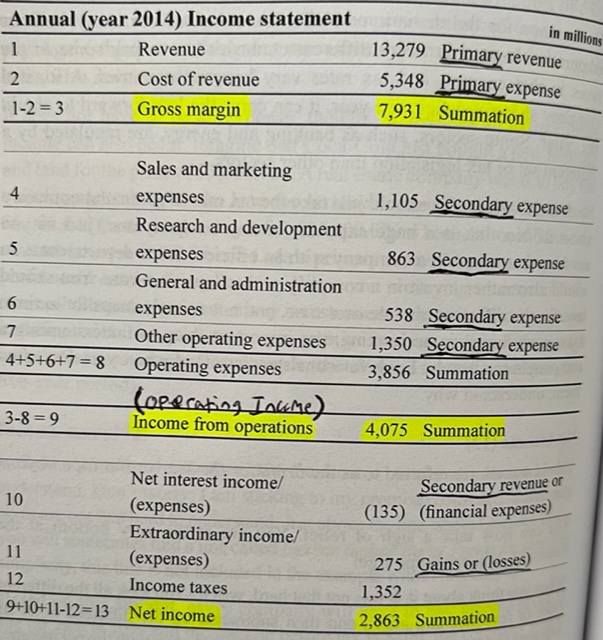

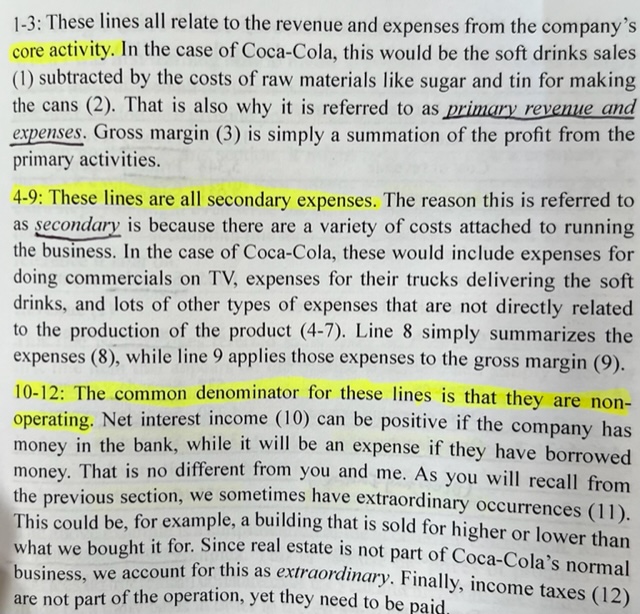

- Income Statement Fundamentals — All income statements are essentially built the same way, but the line items and overall presentation may be slightly different depending on the company. In essence, the income statement is constructed in sections:

- Primary Revenue & Expenses (Top) — This includes revenue/total sales and costs directly associated with making the products.

- Secondary Expenses (Middle) — These are operating expenses, which are costs that come with running the company and are not directly associated with making the products. Examples include marketing, research and development, salaries for employees, etc.

- Non-Operating Income & Expenses (End) — This section outlines the company’s financial activity. If the company made income from the bonds or stocks it is invested in, that income gets reported here. If the company lost money due to its financial activity (by having to pay a lot of interest on its borrowed debt), it is reported here.

- Quote (P. 144): “Most importantly, no matter how you compose your income statement, the intention is always to show how much net income the company has made at the bottom line.”

- Income Statement, Line by Line — The following line items are normally included in every income statement. They might be named slightly different, but these are the typical line items:

- Total Revenue — This is the total sales of the company for the given time period. The starting point for every income statement.

- Cost of Revenue (COGS) — Costs directly associated with making the product or service. Ideally, this number will be as low as possible so the company can make a nice gross margin. If the costs of making the product are almost as much as the product is selling for, that’s obviously not good. Some companies are highly dependent on a certain commodity/raw material to produce their products. If the price of that commodity (i.e. sugar) goes up, its COGS will go up as well. COGS also includes blue-collar labor.

- Gross Margin — Simply the revenue minus the direct costs associated with the production of goods or delivery service. Gross margin is essentially a measure of the organization’s efficiency — the ability of management to control direct costs of revenue while simultaneously increasing sales.

- Selling, General, and Administration — These are secondary costs associated with marketing and distributing the product or service. Staff salaries are also included in this group.

- Research and Development — The pressure to innovate is high. Research and development is a secondary cost associated with exploring and developing new products or services. Depending on the company or industry, these may be high or low. Technology companies typically have high research and development costs.

- General and Administrative — These are often combined into the SGA group above. It’s essentially salary costs for management and office employees.

- Other Operating Expenses — All overhead costs that can’t be categorized in the other line items on the income statement. They are pooled together and lumped into this category.

- Operating Expenses — This is all of the secondary costs of running the business added up.

- Operating Income (EBIT) — This is gross margin minus all secondary costs of running the business. This line item represents earnings before interest and taxes. No financing activity has been accounted for yet at this point, which is why it’s called Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT). The operating income line gives you a good look at how efficient the company is. After all, profitability will only be maximized when the business is able to control its operating expenses while maximizing its revenue.

- Quote (P. 153): “Since financing expenses haven’t been subtracted out of the company’s profit yet, compare this line (income from operations) to the next line down in the statement (titled net interest income/expenses) to gain an understanding of the interest obligations (or debt payments). Think of it like this: let’s assume you made $30,000 for the year after all your regular expenses were accounted for. Let’s also assume you have a large amount of debt that requires hefty interest payments every year. The interest for that debt is $25,000. Based on those figures, you can quickly see that your debt is devouring your ability to save any money over the long haul.”

- Net Interest Income/Expenses — Just like regular people, companies often have cash sitting around that they put into various investments. These investments (whether they are bonds, stocks, savings accounts, cash from rental properties) can produce income. Companies also have to pay interest on the money (debt) they borrow from banks or investors. This line item shows you if the company made money or lost money while participating in these financial activities. In most cases, this line is negative because companies use debt in their capitalization structure and hold on to cash for flexibility.

- Ex. Loan — Let’s say a company takes out a $100,000 loan with 10% interest. That’s $10,000 in interest payments per year. On the income statement, if Operating Income is $20,000 and Net Interest/Expense is -$10,000, you can see that half of the profits are destroyed because of the loan.

- Extraordinary Income/Expenses — Gains or losses that are irregular one-offs are recorded in this line item.

- Income Tax — This line item shows the amount of taxes the company had to pay for the year (or quarter).

- Net Income — What the company made after deducting COGS, operating expenses, taxes, financial expenses, and more. Divide this figure by the number of shares outstanding to get EPS. Earnings are maybe the biggest driver of stock price.

- Income Statement Ratios — Ratios allow you to easily compare a company to others in its industry. They give you great context and allow you to put a company’s story together. Look at a company’s ratios over several years to see trends. Some of the best ratios include:

- Gross Profit Margin Ratio — Gross Profit / Revenue

- Ex. Coke Income Statement Above — $7,931/$13,279 = 59.7%

- This tells us that every time Coke sells $100 in soft drinks, it makes $59.70 in gross profit.

- Ex. Coke Income Statement Above — $7,931/$13,279 = 59.7%

- Operating Income Margin Ratio — Operating Income / Revenue

- Ex. Coke Income Statement Above — $4,075/$13,279 = 30.7%

- This tells us that every time Coke sells $100 in soft drinks, it makes $30.70 in operating income.

- Ex. Coke Income Statement Above — $4,075/$13,279 = 30.7%

- Net Income Margin Ratio — Net Income / Revenue

- Ex. Coke Income Statement Above — $2,863/$13,279 = 21.6%

- This tells us that every time Coke sells $100 in soft drinks, it makes a net profit of $21.60.

- Ex. Coke Income Statement Above — $2,863/$13,279 = 21.6%

- Interest Coverage Ratio — Operating Income / Interest Expense

- Ex. Coke Income Statement Above — $4,075/$135 = 30.2%

- This tells us that Coke would be able to ‘cover’ its interest payments 30 times with money derived from its operating income. That is very safe. An interest coverage ratio of 5 is solid. You don’t want to see a low number here because it indicates the company may have issues staying above water and paying off the interest on its debt.

- Ex. Coke Income Statement Above — $4,075/$135 = 30.2%

- Takeaway — By using ratios like these, you can see where one company is outperforming or underperforming relative to a competitor. Pepsi’s net income ratio was 12.3% for the same year, but its gross profit margin ratio was 62.7% and exceeded Coke’s. By having these two ratios, we automatically know that Pepsi must have significantly more operating expenses or financial activity expenses than Coke.

- Gross Profit Margin Ratio — Gross Profit / Revenue

Ch. 7: Balance Sheet in Detail

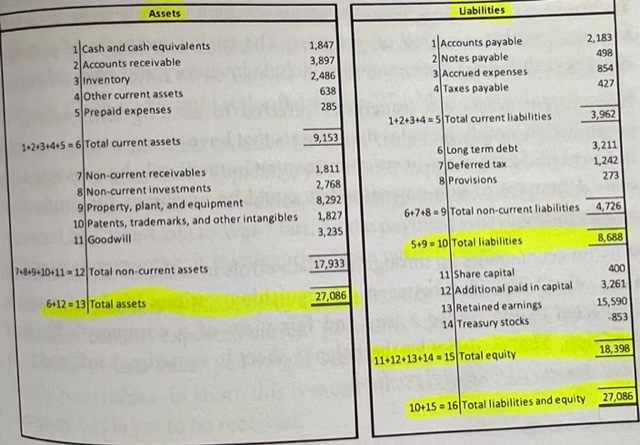

- Balance Sheet Fundamentals — A company owns assets, and those assets are either financed using liabilities or equity. At its core, that’s how simple the balance sheet is; it’s just showing you how the company is paying for its assets such as machines, property, inventory, etc. on a specific day. It’s a snapshot.

- Balance Sheet, Line by Line (Assets) — A company’s balance sheet begins by showing what it owns, or its assets. Assets are things that make money for the company. Current assets can be converted into cash inside of a year. Non-current assets are long-term assets that cannot be converted to cash inside of a year. The line items include:

- Current Asset: Cash & Cash Equivalents — Shows how much pure cash the company has. It also shows cash that is invested in securities, money market funds, savings deposits, etc. and can be liquidated instantly.

- Current Asset: Accounts Receivable — When a company makes a sale on credit, the payment usually takes 60-90 days to come in. Money listed under Accounts Receivable is on the way and will arrive in the next 90 days or so.

- Current Asset: Inventory — Inventory is usually broken down into raw materials, work in progress, and finished goods. This line item summarizes all three. It shows the amount of inventory the company has and how much it’s worth.

- Current Asset: Other Current Assets — These are assets that can be sold in the next 12 months, but are not associated with the categories listed above.

- Current Asset: Prepaid Expenses — These are like subscriptions; they represent items the company paid for in advance will receive over time. I like the example of a Sports Illustrated magazine subscription. You pay for the subscription at the beginning of the year and you receive a new Sports Illustrated magazine to read every month. This is an asset.

- Current Asset: Total Current Assets — This represents all of the assets the company could sell in the next 12 months.

- Non-Current Assets: Non-Current Receivables — Payments expected from customers sometime after the next 12-month period.

- Non-Current Assets: Non-Current Investments — These are investments that the company holds that cannot be sold in the next 12 months. It could be a long-term bond, for example.

- Non-Current Assets: Property, Plant, and Equipment — Tangible assets that can be classified as property, plant, or equipment. This includes buildings, office furniture, etc. Manufacturing companies have bigger PPE balances usually.

- Non-Current Assets: Patents, Trademarks, and Other Intangibles — Trademarks, recipes, patents, and more are stored here. These intangible assets can be very valuable and provide a competitive advantage for some companies. Coke, for example, has tremendous value in its brand name and recipes.

- Non-Current Assets: Goodwill — Goodwill only occurs during an acquisition and is not something the company can create by itself. If Company 1 buys Company 2 by paying more than the book value of assets on Company 2’s balance sheet, the excess is usually recorded as goodwill on Company 1’s balance sheet. Company 1 essentially paid a little extra for Company 2’s brand name.

- Non-Current Assets: Total Non-Current Assets — A summation of all non-current assets listed above. This represents all assets the company cannot sell inside of 12 months.

- Total Assets — This represents everything the company expects to turn into cash at some point, either short term or long term. It’s current assets and non-current assets added together.

- Balance Sheet, Line by Line (Liabilities) — Liabilities, or debt, are one of the two ways a company can pay for its assets, with the other being equity. In order of liquidity, the common liability line items include:

- Current Liabilities: Accounts Payable — The opposite of ‘Accounts Receivable’ in the asset column. Accounts Payable represents the payments the company has to make to suppliers after making orders using credit. These payments are owed to the other companies in the next 60-90 days.

- Current Liabilities: Notes Payable — Notes Payable’ represents short-term debt that a company has to pay back to lenders in the next 30-90 days. It is bonds that are coming due soon.

- Current Liabilities: Accrued Expenses — Companies will often incur expenses that are not yet paid for. This could be expenses for employees’ salaries, electricity bills, or any other payment that is consumed but no yet paid for.

- Current Liabilities: Taxes Payable — This is where the company will list the money that it owes to the federal, state, or local government for the products or services it sells. Once the payment is made to the government from the cash account, you’ll see a deduction in the Taxes Payable account and the tax payment will be listed on the income statement.

- Current Liabilities: Total Current Liabilities — A summation of all current liabilities listed above. This represents all obligations the company expects to pay in cash during the next 12 months.

- Non-Current Liabilities: Long-Term Debt — This is the most significant line in the non-current liabilities section. These are long-term loans obtained by the company. This line gives you a good look at how much debt the company is taking on to finance its operations. Remember, interest payments on these loans are recorded on the income statement. The balance sheet records the principle associated with loans.

- Non-Current Liabilities: Deferred Taxes — A form of deferred taxes companies sometimes pick up.

- Non-Current Liabilities: Provisions — Companies sometimes set aside money here in the event that customers default after making a purchase on credit before they make actual payment. Sometimes this happens.

- Non-Current Liabilities: Total Non-Current Liabilities — Add up the non-current liabilities listed above to find the total amount the company owes, but not in the next 12 months.

- Total Liabilities — This number is found by adding the company’s total current and non-current liabilities.

- Balance Sheet, Line by Line (Equity) — In the end, equity is a form of liability because it’s what the company owes to shareholders. This is why the balance sheet always balances; equity is thrown onto liabilities so both sides of the balance sheet are equal. Along with debt (liabilities), equity is the other way companies can finance their assets. Common line items include:

- Share Capital — Used to keep track of common stock splits and common shares outstanding. It’s a tracking tool for future stock splits and share growth/contraction. Not a significant line item.

- Additional Paid-In Capital — This is where money is recorded when a company decides to sell more shares to the public. The funds raised for those new shares is recorded here. It is simply the difference between the proceeds for the issue of the stock minus the par value (which is only used for bookkeeping as describes under ‘Share Capital.’)

- Retained Earnings — The sum of all the previous net incomes the company has produced. When a company produces earnings, anything not used to pay dividends, buy back shares, or grow the company is transferred into this bucket. It’s a number that keeps accumulating over time as the company produces more earnings.

- Treasury Stock — If a company does a share buyback program, the number here will be negative; it’s how much money the company spent to buy back its shares in the open market. Share buybacks are beneficial to a shareholder for a few reasons:

- Reduces the number of shares in the market, increasing your ownership percentage.

- Drives market price up for existing shares because there are fewer of them in the market.

- Drives Earnings Per Share up, Ashoka because there are fewer shares.

- When a company buys back its own shares, it’s a great sign because it tells you that management believes the shares are undervalued and that the company has a bright future ahead (otherwise they wouldn’t buy the shares).

- Total Equity — Everything that the company owes to shareholders is listed here. This is everything that would be left to shareholders if all assets were liquidated and liabilities were paid off right now. Total equity is added to total liabilities because it’s technically what the company owes to shareholders.

- Total Liabilities and Equity — This line includes everything the company owes to both shareholders and lenders. Total liabilities and equity are always equal to total assets so the balance sheet balances.

- Balance Sheet Ratios — Balance sheet items can be combined with income statement items to produce nice ratios you can use for comparison when evaluating a company. Some of these include:

- Return On Equity — Net Income / Equity

- Ex. Coke Financials Above — $2,863/$18,398 = 15.6%

- This tells us that the company has made a return of $15.60 for every $100 it invests back into the company. You want this number high.

- Ex. Coke Financials Above — $2,863/$18,398 = 15.6%

- Return on Assets (ROI) — Net Income / Total Assets

- Ex. Coke Financials Above — $2,863/$27,086 = 10.6%

- This tells us that for every $100 in assets, the company is making $10.60 in net profit. It shows you how efficiently the company is using its assets.

- Ex. Coke Financials Above — $2,863/$27,086 = 10.6%

- Current Ratio — Current Assets / Current Liabilities

- Ex. Coke Financials Above — $9,153/$3,962 = 2.31

- This tells us that the company has 2.31 times more current assets than current liabilities.

- Ex. Coke Financials Above — $9,153/$3,962 = 2.31

- Acid Test Ratio — (Current Assets-Inventory) / Current Liabilities

- Ex. Coke Financials Above — ($9,153-$2,486)/$3,962 = 1.68

- This tells us that the company has 1.68 times more current assets than current liabilities, even when you take inventory out of current assets.

- Ex. Coke Financials Above — ($9,153-$2,486)/$3,962 = 1.68

- Inventory Turnover Ratio — Cost of Revenue / Inventory

- Ex. Coke Financials Above — $5,348/$2,486 = 2.15

- This tells us that the company was able to turn over its inventory 2.15 times this year. It depends on the industry, but you want this number to be high because it shows that the company is getting though its inventory efficiently.

- Ex. Coke Financials Above — $5,348/$2,486 = 2.15

- Debt-to-Equity Ratio — (Long Term Debt + Notes Payable) / Equity

- Ex. Coke Financials Above — ($3,211 + $498)/$18,398 = 20.2%

- This tells us that the company owes $20.20 in debt for every $100 of equity it holds. This is one of the more important ratios. It gives you insight into how much debt the company has in relation to equity. It gives you an idea as to how the company is capitalized. You preferably want to see a fairly low number here.

- Ex. Coke Financials Above — ($3,211 + $498)/$18,398 = 20.2%

- Liabilities-to-Equity Ratio — Total Liabilities / Equity

- Ex. Coke Financials Above — $8,688/$18,398 = 47.2%

- This tells us that the company owes $47.20 in debt for every $100 of equity it holds. This is also an important ratio. It gives you insight into how much debt the company has in relation to equity companies, but it’s more conservative than debt-to-equity because it considers all liabilities. It gives you an idea as to how the company is capitalized.

- Ex. Coke Financials Above — $8,688/$18,398 = 47.2%

- Return On Equity — Net Income / Equity

Ch. 8: Cash Flow Statement in Detail

- Cash Flow Statement — This statement connects the income statement with the balance sheet — it literally starts with the bottom line of the income statement (net income) and ends with the first line of the balance sheet (cash and cash equivalents). It’s similar to looking at an individual’s checking account every month. It works kind of like that.