Thinking Fast and Slow

Daniel Kahneman

GENRE: Miscellaneous

GENRE: Miscellaneous

PAGES: 499

PAGES: 499

COMPLETED: July 13, 2022

COMPLETED: July 13, 2022

RATING:

RATING:

Short Summary

In a masterpiece that has sold over 2.6 million copies, world-famous psychologist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics Daniel Kahneman takes readers on a tour of the mind by introducing the fictitious System 1 and System 2. Thinking Fast and Slow explains why System 1 is quick, intuitive and emotional, while System 2 regulates self-control and requires slower, more effortful thinking. The book helps readers understand how the mind works and how to spot predictable errors and biases.

Key Takeaways

Favorite Quote

"When information is scarce, which is a common occurrence, System 1 operates as a machine for jumping to conclusions."

Book Notes

Introduction

- Daniel Kahneman — Author of this book and a psychology professor at Princeton University. In 2002, Kahneman and his colleague Amos Tversky won the Nobel Prize in Economics for their work on decision making and judgement.

- Heuristics and Biases — This is where Kahneman and Tversky spent most of their time, and these are discussed at length throughout this book. Heuristics and biases are “rules of thumb” that we use to make decisions and judgements every day. Most of the time, our intuitions are right, but this book discusses some of the “predictable systematic errors” that some of our biases can lead to.

- 1984 — Kahneman and Tversky published their paper on Prospect Theory, which is one of the most cited papers of all time.

Ch. 1: The Characters Of The Story

- Systems Of The Mind — The mind works using two different systems of thinking. One is very fast and instinctive, while the other is very slow and deliberate. Each of the two systems can be thought of as “agents of the mind” and have their own abilities, limitations, and functions. Kahneman and other psychologists refer to these systems at System 1 and System 2.

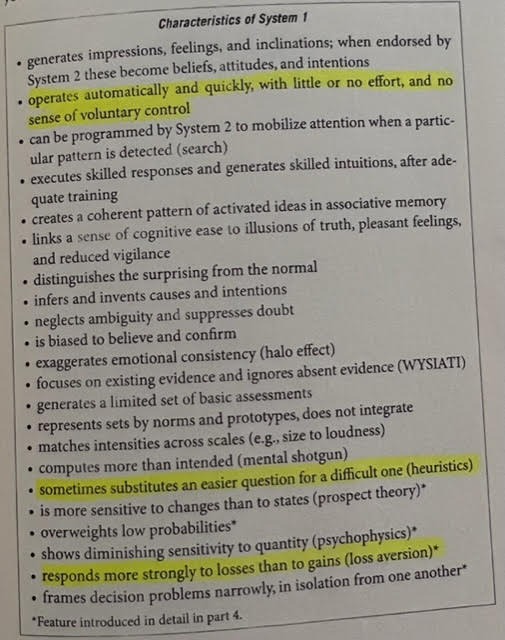

- System 1 — The Automatic System. Used to make quick judgements. Operates automatically and quickly, and cannot be turned off when awake. Requires very little effort and control. Handles very simple tasks. System 1 is instinctive and happens automatically. Your “gut feeling.” System 1 is essentially you on autopilot. Because System 1 activities are usually pretty simple, you’re able to do two or more of these tasks at one time.

- Ex. Reading People — System 1 is what allows you to read people’s facial expressions and know if they are happy, angry, etc.

- System 2 — The Effortful System. In charge of self-control and behavior. Called on when deep, effortful thinking is required to make decisions, carry out tough assignments, monitor behavior, control reactions, or solve complex math problems. Your physical state is altered as System 2 focuses and concentrates — blood pressure goes up, muscles tense, pupils dilate, and heart rate elevates. Activities that rely on System 2 require a lot of attention and are disrupted when attention is drawn away from the task. Because these tasks require a lot of attention, it is really hard to do two of them at one time.

- Ex. Math Problem — 17 x 24

- The Invisible Gorilla — When System 2 is being used, the person temporarily becomes partially blind and deaf because they are focused on the task and their attention is on the task. In their book The Blind Gorilla, Chris Chabris and Daniel Simons had two basketball teams — one dressed in black, the other in white — pass basketballs on two ends of the court. Subjects were instructed to watch one of the teams and count the number of passes (System 2). During the middle of the task, a woman in a gorilla suit ran on the court and pounded her chest. Less than half of the subjects said they saw the gorilla.

- Lesson — If you see someone using System 2, you’re better off not even bothering them, talking to them, or asking a question. Their attention is locked up on something else and they don’t have enough of it to spend on what you’re saying or doing.

- Ex. Driving — When the highway is empty, a driver can operate a car using System 1 and simultaneously carry on a conversation with a passenger. When a driver needs to pass a semi-truck on a narrow part of the highway, System 2 is engaged and the driver has to put his full attention on the road. Any conversation with a passenger would just be distracting and useless in that moment.

- Lesson — If you see someone using System 2, you’re better off not even bothering them, talking to them, or asking a question. Their attention is locked up on something else and they don’t have enough of it to spend on what you’re saying or doing.

- System 1 — The Automatic System. Used to make quick judgements. Operates automatically and quickly, and cannot be turned off when awake. Requires very little effort and control. Handles very simple tasks. System 1 is instinctive and happens automatically. Your “gut feeling.” System 1 is essentially you on autopilot. Because System 1 activities are usually pretty simple, you’re able to do two or more of these tasks at one time.

- System 1 and System 2 Interaction — Most of what you (essentially your System 2) think and do originates in your System 1, but System 2 takes over when things get difficult, and it normally has the last word.

- Quote (P. 24): “System 1 runs automatically and System 2 is normally in a comfortable low-effort mode, in which only a fraction of its capacity is engaged. System 1 continuously generates suggestions for System 2: impressions, intuition, intentions, and feelings.”

- Quote (P. 24): “When System 1 runs into difficulty, it calls on System 2 to support more detailed and specific processing that may solve the problem of the moment. System 2 is mobilized when a question arises for which System 1 does not offer an answer… System 2 is also credited with the continuous monitoring of your own behavior — the control that keeps you polite when you are angry, and alert when you are driving at night.”

Ch. 2: Attention and Effort

- System 2 Is Lazy — Laziness is a defining characteristic of System 2, which helps explain why most people typically do not like to expend more effort than is needed. Because System 2 is lazy, it relies heavily on the instincts of System 1 unless System 1 gets stuck and needs the effortful thinking that only System 2 can supply.

- Quote (P. 31): “In the unlikely event of this book being made into a film, System 2 would be a supporting character who believes herself to be the hero. The defining feature of System 2 is that its operations are effortful, and one of its main characteristics is laziness, a reluctance to invest more effort than is strictly necessary.”

- Law of Least Effort — If several ways to accomplish a task are available, we gravitate towards the least demanding course of action.

- System 2 and Pupils — The more energy, focus, and attention required to complete a task, the more your pupils will dilate. Kahneman tested this early in his career. Pupil sizes increased as subjects performed difficult tasks. When subjects performed a fairly easy task, their pupils stayed relatively the same in size. As you become more skilled at a task, less energy and attention is required to complete it.

- System 2 Directs Attention — System 2 is designed to place most of your attention on the most difficult task you are performing. Any spare attention remaining will be directed towards other activities that require less effort.

- Quote (P. 35): “System 2 protects the most important activity, so it receives the attention it needs; ‘spare capacity’ is allocated second by second to other tasks.”

- Drivers of Effort — We can only hold so much in our working memory at one time. Effort is required to hold in our memory several ideas that require separate actions. Time pressure is another driver of effort. Any task that requires you to keep several ideas in mind at the same time forces you to work hard. Switching between tasks has also been shown to require a lot of effort.

- Ex. Following rules

- Ex. Choosing between multiple options

- Ex. Comparing objects on several attributes

Ch. 3: The Lazy Controller

- Self-Control and Deliberate Thinking Are Linked — When you are in a situation where you need to consciously control your behavior or actions, your ability to think critically diminishes. System 2 has a limited budget of effort and has to decide between one task or the other.

- Ex. Walking — When you walk quickly, it’s almost impossible to do any kind of thinking that requires effort. You have to keep your speed up, which requires self-control. If somebody asked you to multiple 17×24, you would come to a complete stop to attempt the calculation. When walking slowly, you’re able to think much better because you can direct effort there.

- Flow State — A term coined by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. You get into a ‘flow state’ when System 2 is able to lock in on a task without exerting self-control. By not needing to exert energy on self-control to perform the task, System 2 can direct the additional resources to the actual task. In other words, System 2 is not tied up in multiple tasks.

- Ex. Writing — You get into a flow state with writing when you don’t need to force yourself to focus and write. When you don’t have to spend energy on self-control, System 2 can spend extra energy on the actual writing process, which makes it feel easy.

- Quote (P. 41): “In a state of flow, however, maintaining focused attention on these absorbing activities requires no exertion of self-control, thereby freeing resources to be directed to the task at hand.”

- System 2 and Self-Control — System 2 is in charge of thoughts and self-control. Thoughts and self-control require effort and attention. When System 2 is tied up performing a difficult task that requires focus and attention, it has less energy available to focus on self-control and behavior, which is why people sometimes get mad, “snap”, or do something out of character when somebody interrupts them while they are focusing — their System 2 is tied up.

- Quote (P. 41): “People who are cognitively busy are also more likely to make selfish choices, use sexist language, and make superficial judgments in social situations.”

- Ego Depletion — A term in psychology used to describe the depletion of motivation and willpower over time. As you exert self-control to complete a difficult task, your willpower budget is drained. It requires a lot discipline and willpower to then step up and do another demanding task.

- Quote (P. 42): “The evidence is persuasive: activities that impose high demands on System 2 require self-control, and the exertion of self-control is depleting and unpleasant.”

- Quote (P. 42): “After exerting self-control in one task, you do not feel like making an effort in another, although you could do it if you really had to.”

- Glucose Depletion — The nervous system consumes more glucose than most other parts of the body, and effortful mental activity rapidly depletes glucose storages. When you are thinking hard or are in a situation that requires a lot of self-control, your blood glucose level drops. It’s like a runner who burns up a lot of glucose in her muscles during a sprint.

- Refuel — The takeaway here is that you can summon willpower, motivation, and mental energy by simply pumping glucose back into your system.

- Ex. Israeli Judges — Eight parole officers in Israel were monitored as they reviewed cases and paperwork all day. On average, 35% of requests were approved by the judges. But after a meal, these judges approved 65% of requests. During the two hours between their next meal, the judges’ approval rate slowly declined to about 0% right before the meal. These judges were defaulting to the easier position of denying requests as they were losing glucose, energy, and mental capacity.

- Refuel — The takeaway here is that you can summon willpower, motivation, and mental energy by simply pumping glucose back into your system.

- Lazy System 2 — One of the main functions of System 2 is to monitor and control thoughts and actions suggested by System 1. But System 2 is often lazy and will not check System 1 when needed. It will just go along with the first answer, suggestion, or conclusion that System 1 sends it. Effortful thinking takes work, and most people avoid it if they can.

- Bat and Ball Experiment — A bat and ball cost $1.10. The bat costs one dollar more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

- Most people choose 10 cents because that’s the first answer that comes to mind. It’s the intuitive answer from System 1. The correct answer is 5 cents. A small investment of effort by System 2 would have come to the right answer, but people do not want to engage. Most people tend to go with the first plausible answer that requires the least work. More than 50% of Harvard, Princeton, and MIT students have the ‘10 cent’ answer.

- Quote (P. 45): “The bat-and-ball problem is our first encounter with an observation that will be a recurrent theme of this book: many people are overconfident, prone to place too much faith in their intuitions. They apparently find cognitive effort at least mildly unpleasant and avoid it as much as possible.”

- Quote (P. 45): “When people believe a conclusion is true, they are also very likely to believe arguments that appear to support it, even when these arguments are unsound. If System 1 is involved, the conclusion comes first and the arguments follow.”

- Bat and Ball Experiment — A bat and ball cost $1.10. The bat costs one dollar more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

- System 2 Is A Supervisor — System 2 is responsible for supervising System 1. People who blurt things out randomly usually have a weak System 2, and are also suspect or to immediate gratification. People with a weak System 2 usually struggle to delay gratification — they want things right away.

Ch. 4: The Associative Machinery

- Priming — System 1 is very intuitive and forms associations based on things we come in contact with/are primed with, such as words, pictures, events, and more. We often have no control over the associations our mind makes — they happen automatically and unconsciously. Priming can therefore be really powerful.

- Ex. Money — Participants in one study who were primed with images and words involving money were more likely to become independent, self-reliant, and selfish. In one case, participants who were primed with money picked up fewer spilled pencils on the ground for a colleague than those who weren’t primed. The research was conducted by Kathleen Vohs, who has warned of the dangers of being in a culture that surrounds you with reminders of money because of how it can shape your behaviors and attitudes.

- Quote (P. 55): “The general theme of these findings is that the idea of money primes individualism: a reluctance to be involved with others, to depend on others, or to accept demands of others.”

- Ex. Honesty Box — In Britain, a study involving a group of snacks with suggested prices in the office and an honesty box was conducted. Researchers randomly changed the picture near the box from flowers to images of a person’s eyes “watching.” Each week, these images were alternated. On the weeks where there was a picture of somebody’s eyes, people in the office paid a higher price (almost three times more) for their snacks than during weeks where an image of flowers was posted. People were being primed by an image of somebody “watching” them, which led to greater contributions to the honesty box.

- Ex. Weather — A random pleasant, cool breeze on a hot day can make you feel more optimistic about something you are observing in that moment without you even knowing it.

- Ex. Money — Participants in one study who were primed with images and words involving money were more likely to become independent, self-reliant, and selfish. In one case, participants who were primed with money picked up fewer spilled pencils on the ground for a colleague than those who weren’t primed. The research was conducted by Kathleen Vohs, who has warned of the dangers of being in a culture that surrounds you with reminders of money because of how it can shape your behaviors and attitudes.

- Quote (P. 58): “You have now been introduced to that stranger in you, which may be in control of much of what you do, although you rarely have a glimpse of it. System 1 provides the impressions that often turn into your beliefs, it is the source of the impulses that often become your choices and your actions.”

- System 1 is responsible for a lot of our behavior, and we don’t even really have any conscious awareness of what it’s up to. We are very susceptible to priming and association at an unconscious level.

Ch. 5: Cognitive Ease

- Cognitive Ease — System 1 is like a cockpit in an airplane. It constantly monitors your wellbeing and one of its chief functions is to determine if extra effort is required from System 2. Cognitive ease is one of the dials in the cockpit and ranges from “easy” to “strained.” When a task is too tough for System 1, it calls on System 2 for help. Psychologists believe all of us live much of our lives guided by System 1.

- Presentation Is Key — You experience cognitive strain when you read text that is poorly presented. System 2 is called in to try to interpret the information. This is why, in marketing, it’s so important to present the information using subheads, bullets, etc. to make it as easy as possible on the reader.

- Quote (P. 64): “If possible, the recipients of your message want to stay away from anything that reminds them of effort.”

- Interestingly, one experiment found that students at Princeton scored much higher on a basic test when the questions were presented with poor font and formatting than rather than neatly presented. This is because System 2 was called on to interpret and the students were less likely to just go with the first answer System 1 came to.

- Presentation Is Key — You experience cognitive strain when you read text that is poorly presented. System 2 is called in to try to interpret the information. This is why, in marketing, it’s so important to present the information using subheads, bullets, etc. to make it as easy as possible on the reader.

- The Exposure Effect — Familiarity leads to trust. The more we hear or see something, the more likely we are to trust it and like it. System 1 is quick to question things that aren’t familiar. Words or statements we’ve seen or heard many times are almost automatically believed by our intuitive System 1.

- Mood — Your mood has a direct impact on the operation of System 1. When you are uncomfortable and unhappy, you lose touch with your intuition. A happy mood also loosens the control of System 2 over performance: when you’re in a good mood, you become more intuitive and creative, but you are also more susceptible to making errors because System 2 loosens up.

Ch. 6: Norms, Surprises, and Causes

- Causality — System 1 likes to link events together and make connections. The mind can’t resist trying to make up a story to explain things. Our mind likes to develop reasons and assumptions for why something happened, even if we are completely off base.

- Ex. Saddam Hussein’s Capture — Bond prices initially rose when Saddam Hussein was captured and the headline in the Bloomberg News read: “US TREASURIES RISE; HUSSEIN CAPTURE MAY NOT CURB TERRORISM.” Half an hour later, bond prices fell and the the revised headline read: “US TREASURIES FALL; HUSSEIN CAPTURE BOOSTS ALLURE OF RISKY ASSETS.” These contradictory headlines are an example of how we like to make sense of certain things by making assumptions.

Ch. 7: A Machine For Jumping to Conclusions

- Jumping to Conclusions — Our mind is programmed to jump to conclusions and make assumptions when the dots aren’t fully connected in a story. We like to guess. System 1 tends to believe things. It’s very gullible. System 2 is in charge of “unbelieving” things. But research hers have shown that, when System 2 is busy, we will believe almost anything.

- Quote (P. 79): “Jumping to conclusions is efficient if the conclusions are likely to be correct and the cost of an occasional mistake acceptable, and if the jump saves much time and effort. Jumping to conclusions is risky when the situation is unfamiliar, the stakes are high, and there is no time to collect more information.”

- Quote (P. 81): “Understanding a statement must begin with an attempt to believe it: You must first know what the idea would mean if it were true. Only then can you decide whether or not to unbelieve it.”

- Quote (P. 81): “The moral is significant: when System 2 is otherwise engaged, we will believe almost anything. System 1 is gullible and biased to believe, System 2 is in charge of doubting and unbelieving, but System 2 is sometimes busy, and often lazy.”

- Confirmation Bias — We look for confirming evidence to support our already held beliefs, rather than consider evidence that doesn’t support our beliefs.

- Ex. Question — When asked “Is Sam friendly?”, we immediately search our memory for examples of when Sam was friendly. If we are asked “Is Sam unfriendly?”, we immediately search our memories for examples of when Sam was not friendly.

- The Halo Effect — Our tendency to like everything about a person. If you like someone, you tend to assume they are great in other areas, even when you don’t know that for a fact. Again, we have a huge tendency to assume.

- Ex. Generosity — You like someone. When you are asked if that same person would be willing to donate to charity, you tend to believe they are generous and would donate even though you have no evidence that they are a generous person.

- Ex. Work — Somebody makes a nice presentation at work. You automatically assume that person has great management skills even though you have no evidence of that.

- Ex. Baseball — A pitcher is handsome and athletic. You assume he throws the ball really well. Alternatively, a pitcher is ugly and unathletic. You assume he throws the ball worse than he actually does.

- Weighted Halo Effect — The sequence of presented information matters. The Halo Effect increases the weight of first impressions, sometimes to the point that subsequent information is mostly wasted. In other words, what we see first in a string of information is more influential than what we see later on in the string.

- Ex. Grading — Kahneman found that he would grade students better if their first essay was really good on a test. On the following essays later in the test, he would give the student the benefit of the doubt on mistakes. The first essay served as the first impression. If it was good, he was more lenient with grading. If it was bad, he assumed the student was bad based on the first essay and he graded more harshly on the rest of the test.

- Stories — System 1 loves to create stories, make assumptions, and jump to conclusions. When there isn’t enough information available, we can’t stand not being able to connect the dots — we have to complete the story in our mind. This is why we love to assume things.

- Quote (P. 85): “When information is scarce, which is a common occurrence, System 1 operates as a machine for jumping to conclusions.”

- WYSIATI — What You See Is All There Is. Our mind works in alignment with this rule constantly. Basically, we take whatever information is available to us and build the best possible story with that limited information. If it’s a good story, you believe it. Interestingly, if there is less information available, it’s easier to create a story because there are fewer pieces to fit into the puzzle. You don’t even bother to go out and find additional information that might influence your story. If there is a lack of information to fully connect the dots in the story, we will make things up/assume things to connect the dots. WYSIATI is at play everywhere, both in our personal and professional lives.

Ch. 8: How Judgements Happen

- Basic Assessments — System 1 continuously monitors what is going on outside and inside the mind, and continuously generates assessments of the situation with little or no effort. These judgements are referred to as basic assessments. These basic assessments developed in early humans and are critical to our survival and wellbeing.

- Ex. Friend or Foe — System 1 can instantly judge whether somebody is a friend or a foe based on facial structure and body language. Several studies have analyzed this ancient ability by studying political candidates; candidates with a strong chin and a slight smile have historically performed better in political races.

Ch. 9: Answering An Easier Question

- Substitution — When faced with a difficult question, rather than answer it System 1 likes to replace the question with an easier question and then answer the easier question. This is why we are rarely stumped, even by really tough questions that we don’t even fully understand. This is also why we have intuitions about people and things that we don’t know much about — these intuitions come from answering easier questions. As we know, System 2 is lazy and will often just accept the answer to the easier question rather than put the effort into answering the actual difficult question.

- Quote (P. 97): “If a satisfactory answer to a hard question is not found quickly, System 1 will find a related question that is easier and will answer it.”

- Quote (P. 97): “You like or dislike people long before you know much about them; you trust or distrust strangers without knowing why; you feel that an enterprise is bound to succeed without analyzing it.”

- Ex. President — Here is an example of this tendency to substitute in action.

- Difficult Question — How popular will the president be six months from now?

- Substitute Easy Question — How popular is the president right now?

- Mood Heuristic — Another example of substituting comes from a study conducted in Germany. Students were asked the following two questions. The first batch of students were asked the questions in the order presented below. The second batch of students were asked the two questions below but in reverse order.

- How happy are you these days?

- How many dates did you have last month?

- Results — Researchers found that there was no correlation between happiness and dates with the first batch of students. But there was a huge correlation between happiness and dates with the second batch of students. By first having to assess their love life before answering the question about overall happiness, the second batch of students essentially used their love life happiness as a substitute answer to the question about overall happiness because their level of satisfaction with their love life was on their mind first, and overall happiness is a difficult question to answer without some effort.

- Quote (P. 102): “The students who had many dates were reminded of a happy aspect of their life, while those who had none were reminded of loneliness and rejection. The emotion aroused by the dating question was still on everyone’s mind when the query about general happiness came up.”

- Results — Researchers found that there was no correlation between happiness and dates with the first batch of students. But there was a huge correlation between happiness and dates with the second batch of students. By first having to assess their love life before answering the question about overall happiness, the second batch of students essentially used their love life happiness as a substitute answer to the question about overall happiness because their level of satisfaction with their love life was on their mind first, and overall happiness is a difficult question to answer without some effort.

- Affect Heuristic — We let our likes and dislikes determine our beliefs about the world. If we like a certain thing, especially in an emotional way, we shut out logic and believe everything about it is good. In this way, we are somewhat blind to counter arguments. We just assume everything about the thing is great.

- Ex. Project — If a manager really likes the idea of a certain project, he will most likely also believe that the costs of the project are low and the benefits of the project are high. He doesn’t know these things for a fact, but he is emotionally invested in the project because he likes the idea of it.

- Quote (P. 103): “Your emotional attitude to such things as irradiated food, red meat, nuclear power, tattoos, or motorcycles drives your beliefs about their benefits and their risks. If you dislike any of these things, you probably believe that its risks are high and its benefits negligible.”

Ch. 10: The Law of Small Numbers

- The Law of Small Numbers — Small sample sizes lead to extreme results on both ends of the spectrum. Large sample sizes yield much more accurate results. We also pay far more attention to the content of a message than to the information about its reliability (like sample size). As a result, we have a view of the world that is much more simple than what it really is. Trusting System 1 and our intuition by jumping to conclusions is more convenient.

- Ex. Kidney Cancer — Counties that have the lowest percentage of kidney cancer in the country are rural. Counties with the highest percentage of kidney cancer are also rural. The low population size in rural counties explains why both of these statements are true.

- Ex. Reviews — If there are only a small number of reviews about a product, you’re likely to get extreme ratings (like 2 stars or 5 stars). If there are a ton of reviews, you can trust the ratings a lot more.

- Random Events — Because System 1 likes to connect dots and engage in causal thinking, we like to come up with causes for random events, even when no explanation is needed and the event is just truly random. Many facts of the world are simply due to chance.

- Ex. Basketball — In basketball, the sequence of made and missed shots has been tested and shown to be completely random. But when a player hits a few shots in a row, everybody believes he has a “hot hand.” In reality, it’s completely random. But System 1 loves to think causally and connect dots — we tend to go with our intuition rather than believe something is random.

- Quote (P. 117): “If you follow your intuition, you will more often than not err by misclassifying a random event as systematic. We are far too willing to reject the belief that much of what we see in life is random.”

Ch. 11: Anchors

- The Anchoring Effect — One of the most reliable and robust results of experimental psychology. Anchoring occurs when you don’t know the value of something. Because you are uncertain, you tend to anchor yourself to a suggested number and come to a final value/answer that is near that suggested number.

- Ex. Gandhi — If someone asked you if Gandhi was 114 years old when he passed away, your estimate of when he died will be much higher than if you were asked if he was 35 years old when he died. Depending on the number thrown out to you, you will anchor yourself and stay somewhere in near that range.

- Ex. Real Estate — Anchoring occurs with asking prices. If you consider how much you should pay for a house, you will be influenced by the asking price. The same house will appear more valuable if its listing price is higher than if it is low, even if you were determined to resist the influence of the number.

- Anchor and Adjust — Occurs when you start at an anchoring number, assess whether it’s too high or low, and adjust your estimate by mentally moving away from the anchor. You will not stray too far from the starting number/anchor as you adjust. System 2 is involved here.

- Ex. George Washington — When was George Washington elected President? Your anchor will likely be 1776, and you’ll adjust from there.

- Case Study: Anchoring and Real Estate — Anchoring can be found in almost any area of life. Anchoring is everywhere. One study tested anchoring on trained real estate agents. There were two groups of agents — both groups were brought to a home that was for sale and were asked to look around the house and read a booklet, which included an asking price. For Group 1, the asking price listed was really high. For Group 2, the asking price listed was really low. Agents in both groups were then asked to name a “reasonable buying price for the home.”

- Results — The agents in both groups named suggested buying prices that were very close to the asking price listed in their respective booklets (the anchor). The difference in suggested buying prices between the agents in both groups was huge; agents in both groups started with their anchor and adjusted from there.

- Case Study: Anchoring and Courts — One study tested anchoring on a group of German judges with 15 years of experience. The judges were told to roll a loaded die that landed on either 3 or 9 every time after first reading a passage about a shoplifter. The judges were then asked to say how much prison time they would sentence the shoplifter to.

- Results — The judges who rolled a 9 said, on average, said they would sentence the shoplifter to 8 months in prison. The judges who rolled a 3, on average, said they would sentence the shoplifter to 5 months in prison.

- Quote (P. 128): “You should assume that any number that is on the table has had an anchoring effect on you, and if the stakes are high you should mobilize yourself (your System 2) to combat the effect.”

- Anchoring is everywhere. If you pay attention, you’ll see it in many scenarios in your daily life.

- Use anchoring to your advantage, especially in negotiations, but don’t use it abusively.

Ch. 12: The Science of Availability

- The Availability Heuristic — The process of judging how often something happens based on how easily you can recall similar instances happening in your memory. You substitute a hard question with an easy one by estimating the frequency of an event based on how easily the incident is found in your memory. This can lead us to develop biases.

- Ex. Divorces — If you hear about divorces from your friends or on the news consistently, you are easily able to recall these instances of divorce in your memory and that makes you biased towards thinking divorce is a common thing in the world. It isn’t really true, but you were easily able to recall incidents of divorce happening in your memory. That’s the availability heuristic.

- Ex. Plane Crashes — If you have recently seen a few plane crashes on the news, you’re likely to be impacted by that and feel uneasy about planes. These incidents are easily retrievable in your memory.

- Ex. Confidence — If you’ve had a few recent successes, you become confident because you’re able to easily recall incidents in which you were successful in your memory. These incidents are readily available in your mind. You can see how availability bias can affect confidence — if you’re constantly producing good results, you’re able to easily retrieve incidents of success in your mind and it shapes your self-image. If you’re consistently producing bad results, these incidents are readily available in your memory and you end up exaggerating your bad performance, which leads to a lack of confidence.

- Availability Bias — These are the biases we form from the availability heuristic. Because we care most about ourselves, we easily recall things we’ve done, which can lead to biases.

- Ex. Personal Contributions — When working on a project, it’s very easy to be biased and think you have contributed more than everyone else. That’s because you know what you’ve done and it’s all readily available in your memory. We are all wired like this, so there’s a good chance everybody else feels that way too.

- Quote (P. 131): “You will occasionally do more than your share, but it is useful to know that you are likely to have that feeling even when each member of the team feels the same way.”

- Ex. Chores — One famous study asked each member of a marriage to assess how much they contributed (as a percentage) to chores around the house. As expected, both the man and woman in most cases experienced availability bias and listed their contributions as over 100%. They were able to easily recall in their memory incidents in which they did a chore, which led to a self-contribution bias.

- Ex. Personal Contributions — When working on a project, it’s very easy to be biased and think you have contributed more than everyone else. That’s because you know what you’ve done and it’s all readily available in your memory. We are all wired like this, so there’s a good chance everybody else feels that way too.

- Case Study: Availability Bias — One landmark German study asked subjects to name 12 incidents in which they were “assertive.” Naming 12 incidents in which you were assertive is a lot, and most participants were able to do it, but it was a struggle to name 12. Most participants were able to name a few easily off the bat, but struggled towards the end. The fact that it was a struggle to name 12 — even though 12 is a lot — led most participants to report that they were “not assertive” when asked at the end of the study. In fact, people that were only able to quickly name 6 instances in which they were assertive and then immediately gave up actually gave themselves a higher assertive rating than those who named 12 but really struggled to do so. The people who named 6 quickly and stopped felt they were easily able to retrieve incidents of assertiveness in their memory, which led them to label themselves as highly assertive. This is availability bias in action.

Ch. 13: Availability, Emotion, and Risk

- Availability Dims — Availability bias tends to dim over time. As a certain incident or fact begins to fade in our memory, the availability bias we once had, and the emotion that is tied to it, also fades.

- Ex. Famous Death — When a famous person dies tragically, it tends to snap things back in perspective. The little things that we worried about or bothered us lose their significance. This improved perspective on life tends to last for a few days or a few weeks, but it eventually fades as time goes on.

- Availability Cascade — Because it has the ability to spread information to the masses, the media is a big contributor to availability biases. The media focuses on stories that people find interesting, frightening, concerning, etc. because that’s what drives eyeballs to the television. It’s what allows a news station to compete. By constantly covering stories that produce emotion, the stories are readily available in an individual’s memory, which leads to the development of availability biases and extreme reactions to small risks. When biases develop, people get all fired up and emotional, which is a story in itself, which leads to additional media coverage of the topic. It’s a cycle.

- Quote (P. 139): “Frightening thoughts and images occur to us with particular ease, and thoughts of danger that are fluent and vivid exacerbate fear.”

- Ex. The Alare Scare — In 1989, the “Alare Scare” took the world by storm. Alar is a chemical that was sprayed on apples to regulate their growth and improve appearance. The scare began when the media reported on the chemical and how it had caused cancerous tumors in mice. This caused people to develop an availability bias and freak out, which led the media to cover the story even more. The apple industry sustained huge losses and people feared apples. The FDA later banned the chemical. Subsequent researched showed that there was nothing to worry about and the whole reaction was overblown.

- Ex. Terrorism — In reality, terrorism is not a very big threat. Even in Israel, a country that has been the target of many attacks, the number of casualties from terrorist acts is very small compared to something like traffic accidents. But the gruesome images of terrorism, endlessly repeated in the media, cause everyone to be on edge. The difference between terrorism and traffic accidents is the availability of the two risks — the ease and frequency with which they come to mind in our memory. The media often covers terrorism more often than traffic accidents, which leads to the availability bias.

Ch. 14: Tom W's Specialty

- Representativeness Heuristic — System 1 is intuitive and will deliver judgements and predictions based on the description of a person or object instead of the probabilities. Essentially, we predict things about a person based on their description or way of being rather than leaning on probabilities of an outcome.

- Ex. Reading — You see a person reading The New York Times on the New York subway. Which of the following is a better bet about the reading stranger?

- She has a PhD.

- She does not have a college degree.

- Representativeness (the actual description of the person and what she’s reading) would tell you to bet on the PhD, but this is not necessarily wise. You should seriously consider the second alternative, because many more nongraduates than PhDs ride in New York subways. In other words, there is a greater probability that the person in the description does not have a college degree because PhDs are likely not on a subway.

- Ex. Reading — You see a person reading The New York Times on the New York subway. Which of the following is a better bet about the reading stranger?

Ch. 15: Linda: Less Is More

- Less is More — When it comes to judgments of likelihood, more information about the subject can make it harder to arrive at the right conclusion. We get tied up in the narrative or description when too much information is presented. Kahneman and his colleagues ran one experience where they asked subjects to consider two descriptions of a made up woman named Linda:

- Linda is a bank teller.

- Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

- Results — 85-90% of university students selected No. 2, contrary to logic. The additional detail about Linda’s involvement in the feminist movement makes you think it is less likely that she is a bank teller because the probability of her being a bank teller AND a feminist activist is a less likely outcome than Linda being just a bank teller.

Ch. 16: Causes Trump Statistics

- Base Rates — We tend to put much more weight on stories over statistics and numbers. Our System 1 loves causal stories. If we see a statistic by itself, it doesn’t move us much. On the other hand, if we see the statistic as part of a story that shows why it’s important, it clicks because we like to think causally. There are two main types of base rates that we come in contact with:

- Statistical Base Rates — Facts about a population to which a case belongs. We normally don’t pay any mind to these. We much prefer stories.

- Causal Base Rates — Change your view of how the case came to be. These are pieces of information about the individual case.

- Ex. Cabs — Two companies (Blue and Green) operate the same number of cabs. Green cabs are involved in 85% of accidents. Our immediate preference is to make the connection and assume that Green can drivers are reckless and crazy. That’s just how System 1 works.

- Stereotyping — Occurs in System 1 because of its desire to make assumptions and categorize people and things. System 1 likes to create prototypical examples in the mind that help us recognize things and form an interpretation of the world around us. These prototypical examples are stereotypes. When we meet someone who fits the pro typical image on our mind, we place them in that stereotype.

- Social Responsibility — Richard Nisbett and his colleagues ran a “Helping Experiment” at the University of Michigan in which 15 participants in individual booths spoke with each other over an intercom. One staged participant was instructed to pretend he was having a seizure to see what the other participants would do.

- Result — 4 of the 15 participants responded immediately to the appeal for help. Six never got out of their booth, and five others came out only after the “seizure victim” apparently choked.

- Takeaway — The experiment shows that individuals feel relieved of responsibility when they know that others have heard the same request for help. We all think we would rush to help someone in need, but the presence of others ultimately makes you feel a reduced sense of personal responsibility. When you’re around other people and in a similar situation, push past this natural tendency.

Ch. 17: Regression to the Mean

- Regression to the Mean — Praise and punishment aren’t very helpful when trying to influence performance. Most people’s performance will naturally regress to the mean, whether they just turned in a great performance or a bad one. If somebody just performed poorly, their next outing will likely be much better. On the other hand, somebody that just turned in a great performance will likely fall back on the next outing. Because our intuitive System 1 loves to think causally, we tend to believe that praise or punishment — or some other extraneous reason — was responsible for the change in performance. In reality, it’s all a regression to the mean — praise or punishment isn’t likely to influence the next performance much. This is good to know when you become a manager.

- The Performance Paradox — Because we tend to naturally get a better performance from somebody after a poor one, we get a false representation of punishment. Because we like to think causally, we assume that the punishment is what led to the improved performance on the next outing. In reality, it’s all just a regression to the mean; the punishment wasn’t the reason for the improved performance.

- Quote (P. 176): “Because we tend to be nice to other people when they please us and nasty when they do not, we are statistically punished for being nice and rewarded for being nasty.”

- The Performance Paradox — Because we tend to naturally get a better performance from somebody after a poor one, we get a false representation of punishment. Because we like to think causally, we assume that the punishment is what led to the improved performance on the next outing. In reality, it’s all just a regression to the mean; the punishment wasn’t the reason for the improved performance.

- Regression to the Mean: Golf — One example of regression to the mean can be observed in a golfer’s score throughout a four-day tournament. If a player comes out and shoots a 65 on Day 1, he’s likely to regress to the mean a bit and shoot somewhere closer to par (72) on Day 2. Luck plays a big role in success. There’s a good chance the golfer was a little lucky on Day 1, which may or may not occur again on Day 2.

- Regression to the Mean: Sports Illustrated Jinx — A lot was made of the “Sports Illustrated Jinx” many years ago. Players featured on the cover of Sports Illustrated tended to perform worse and come under public scrutiny after appearing on the cover. We like to think causally and make connections, so most people automatically believed the player “couldn’t handle the pressure” of being on the cover. In reality, getting on the cover required a great season that likely had some luck involved. The inability to match the elite performance that got the player on the cover is simply a regression to the mean. There’s really no causal reason for the drop-off in performance.

- Causal Thinking — The reason we have a hard time understanding and believing the concept of regression to the mean is that we are heavily influenced by our intuitive System 1. Again, we naturally love to make assumptions, connect the dots, and create stories in our mind, even when it isn’t warranted. Our mind is strongly biased towards causal explanations and does not deal well with “mere statistics.”

- Quote (P. 182): “Causal explanations will be evoked when regression is detected, but they will be wrong because the truth is that regression to the mean has an explanation but does not have a cause.”

Ch. 18: Taming Intuitive Predictions

- Extreme Predictions — Our intuitive System 1 loves to make extreme predictions and forecasts based on current evidence in front of us right now. These extreme predictions are evident everywhere, from how we expect a standout 4th grader to perform in college to how aggressively we predict a company will grow its annual sales over time to how we expect a football team to finish a season after a hot start. This tendency to make extreme forecasts is one again part of System 1’s obsession with creating stories and connections — we take the evidence in front of us, create a story in the mind, and then make an extreme forecast that is based on the limited current evidence.

- Ex. 4th Grader — Johnny is a 4th grader who is showing unusually skills and talent. He’s getting straight A’s and is at the top of his class. As Johnny’s parent, our intuitive, System 1 prediction for Johnny is that he will be a straight A student in college and go on to make big money in whatever profession he chooses. In this case, we are taking current evidence and making an extreme forecast. We do this naturally and automatically.

- Quote (P. 186): “When a link (current evidence) is found, your associative memory quickly and automatically constructs the best possible story from the information available.”

- Quote (P. 188): “Prediction matches evaluation. This is perhaps the best evidence we have for the role of substitution. People are asked for a prediction but they substitute in evaluation of the evidence, without noticing that the question the answer is not the one they were asked.”

- Ex. Football — Analysts look at a team on a four-game winning streak and start to make predictions that the team will go on to win the Super Bowl. Rather than make a well-thought out prediction that considers regression, our tendency is to look at current evidence, evaluate it, then use that evaluation to make a big prediction.

- Question Your Predictions — Kahneman makes a case in this chapter for taming your extreme intuitive predictions by factoring in regression to the mean. Understanding that these extreme System 1 predictions occur naturally is a good first step. In the Johnny example above, it’s entirely possible that his great performance is unusual and he will regress to the mean and not perform as well in the years between 4th grade and college. It’s entirely possible he will get distracted and simply not excel in school in the future. System 2 needs to be called in to analyze the situation further before making predictions about things, especially if it’s an important, high stakes prediction where mistakes are costly.

- Quote: (P. 190): “Intuitive predictions need to be corrected because they are not regressive and therefore are biased.”

- Quote (P. 194): “Extreme predictions and a willingness to predict rare events from weak evidence are both manifestations of System 1. It is natural for the associative machinery to match the extremeness of predictions to the perceived extremeness of evidence on which it is based — this is how substitution works. And it is natural for System 1 to generate overconfident judgments, because confidence is determined by the coherence of the best story you can tell from the evidence at hand. Be warned: your intuitions will deliver predictions that are too extreme and you will be inclined to put too much faith in them.”

Ch. 19: The Illusion of Understanding

- Narrative Fallacy — Flawed stories of the past shape our views of the world and expectations for the future. System 1 loves stories and uses them to help us understand things. Most of the time, the stories are flimsy and based on incomplete evidence, but we believe them because they are simple, easy to understand, and focus on things that did happens vs. things that didn’t happen.

- Ex. Google — We believe that Google’s founders operated with amazing intelligence and decision-making to get the company off the ground, which is partly true. But they were also lucky. Creating a billion-dollar company doesn’t happen every day, there was a lot of luck involved. Things had to bounce their way because they had no experience building this type of company before — nobody has. But the story we tell ourselves mostly involves the founders using incredible skills and smarts to build the company.

- Hindsight Bias — Once an outcome has occurred, we act like we knew what was going to happen beforehand when we really had no idea. After an outcome has occurred, we have a hard time remembering what we thought before the decision was made. We are prone to blame decision makers for good decisions that worked out badly and to give them too little credit for successful moves that appear obvious only after the fact.

- Hindsight Bias and Risk-Taking — The fear of hindsight bias is why employees and managers are often too timid to take risks. When a good decision is made but it doesn’t work out, upper-level management experiences hindsight bias and acts like the decision was doomed from the start when it was really a solid decision and just didn’t pay off. This fear of being held accountable for good decisions that don’t work out prevents organizations from really pushing forward and taking smart risks.

- Quote (P. 203): “Hindsight bias leads observers to assess the quality of a decision not by whether the process was sound but by whether its outcome was good or bad.”

- Ex. Third-Base Coach — A third-base coach in baseball is a good example of hindsight bias. When a third-base coach sends a runner home and the runner is thrown out, everybody watching the game acts like it was an obvious decision to hold the runner at third. That’s hindsight bias.

- Luck and Success — Luck plays a big role in success, a far bigger role than most of us acknowledge. System 1 likes stories and causes, so we assign reasons to certain situations where somebody or something has had success.

- Ex. CEO — CEOs certainly do have an impact on how a company performs, but it’s less of an impact than we like to think. When a company is doing great, the halo effect kicks in and we think the CEO is spearheading the charge and doing everything right. When the same company is performing poorly the next year, we think the same CEO is not getting it done. This is an example of hindsight/outcome bias as well. In this case, our perception of the CEO is based on how the company is performing. In reality, the CEO doesn’t have THAT much of an impact, it’s more random than our intuitive System 1 likes to lead us to believe.

- Quote (P. 207): “The comparison of firms that have been more or less successful is to a significant extent a comparison between firms that have been more or less lucky.”

Ch. 20: The Illusion of Validity

- Illusion of Validity — Confidence in our opinions is subjective and comes from the story System 1 and System 2 have constructed in our mind. System 1 loves to develop stories with the information available (WYSIATI), even if the information is weak. The Illusion of Validity refers to the overconfidence we sometimes have in our skills, predictions, and stories. Long-term forecasting is generally inaccurate and doesn’t account for all information, so we really shouldn’t be super confident about our bold predictions and forecasts about the distant future. When somebody is very confident about a prediction, it just means that they strongly believe the story they’ve spun in their mind.

- Quote (P. 212): “Declarations of high confidence mainly tell you that an individual has constructed a coherent story in his mind, not necessarily that the story is true.”

- Ex. Military Training — As part of his service to the Israeli military, Kahneman was responsible for evaluating candidates for officer training. This is where he first observed the Illusion of Validity. He and his colleagues had to watch candidates as they worked together to accomplish tasks on a simulated battlefield. Kahneman was able to see how each officer led, executed, and worked with others. He then gave each candidate a score. The score was a reflection of the candidate’s performance on the battlefield and a prediction as to how well they would perform in officer training. Kahneman always followed up on his candidates to see how they turned out and he found that his prediction about each candidate was almost always wrong. Essentially he and his colleagues spun up a story based on what they observed on the simulated field and tried to predict the candidate’s future performance. Most of the time, the predictions were inaccurate.

- Overconfident Forecasts — Because of hindsight bias, we think we understand the past and the factors that led to certain outcomes because everything makes sense in hindsight. This belief that we understand the past makes us overconfident about our ability to predict the future. Ultimately, the world is unpredictable. It’s impossible to predict the future with accuracy. Anybody who makes long-term predictions (i.e. television pundits) with a high degree of confidence simply strongly believes the story in their mind, which is based on limited evidence. Just because somebody in an authoritative position makes a forecast and appears confident while doing so does not mean their predictions will be true or accurate.

- Ex. Pundits — In his 2005 book Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know?, Philip Tetlock interviewed 284 political pundits and collected 80,000 predictions by asking a series of questions about the future. He then tracked those predictions. The results were devastating — the “expert” pundits performed horribly.

- Illusion of Validity: Finance — Kahneman makes a case that stock picking is completely random and fund managers/other people who trade stocks for a living are “playing a game of chance, not skill.” The process of evaluating a company does take skill and training, but Kahneman argues that the information is already priced in with most stocks and there’s really no way to “beat” the market. He acquired data from one financial from that showed every trade 25 different advisors made over an 8-year stretch. He then ran a few tests and found that the correlation coefficient was essentially 0 — in other words there is really no skill in stockpicking.

- Quote (P. 217): “Unfortunately, skill in evaluating the business prospects of a firm is not sufficient for successful stock trading, where the key question is whether the information about the firm is already incorporated in the price of its stock.”

- Efficient Market Hypothesis — Kahneman’s findings seem to support the Efficient Market Hypothesis, which essentially states that all available information about a company is already priced in to the stock.

Ch. 21: Intuitions vs. Formulas

- Formulas > Intuition — In some cases, not all, formulas and algorithms are more accurate and reliable with predictions/forecasts than our subjective System 1 intuition. Humans are prone to intuitive errors and biases, whereas formulas do not suffer these problems. Given the input, they always return the same answer. To maximize predictive accuracy, final decisions should be left to formulas. Formulas simply make less mistakes. We are starting to see an increasing reliance on formulas and statistics in sports like baseball and football. We are also seeing the emergence of “Robo Advisors” in the financial industry.

- Paul Meehl — One of the most interesting psychologists of the 20th Century, Meehl reviewed the results of 20 studies that had 14 school counselors try to predict future performance of their students. An algorithm that used much less information about the students than the counselors were provided was also created to predict performance. Meehl reported that the algorithm was more accurate than 11 of the 14 counselors.

- Orley Ashenfelter — An economist at Princeton, Ashenfelter created a formula based on weather patterns and other factors to predict the value of fine Bordeaux wine from information available in the year they are made. His formula is extremely accurate — the correlation between his predictions and actual prices is above .90. The wine experts have been far less accurate, partly because they are prone to errors in intuitive biases and judgements.

- Robyn Dawes — Showed that marital stability can also be assessed using a formula: Frequency of Lovemaking – Frequency of Quarrels.

- Virginia Apgar — Former anesthesiologist who created the Apgar Test in 1953, which is a formula used to evaluate newborn babies within one minute of their birth. The formula factors in a baby’s heart rate, respiration, reflex, muscle tone, and color, and grades each one on a scale of 0-2. Combined scores of 8 and above are great, scores of 4 and below are alarming. This test is still used in delivery rooms today. Prior to this test, physicians used intuitive judgements to evaluate babies, which led to missed danger signs and many newborn deaths across the country.

- Do It Yourself — Anybody can create simple formulas for almost any scenario to reduce the possibility of intuitive errors. If you have to hire somebody, for example, follow the steps below:

- Select 5 or 6 traits that are required for success in the position (i.e. technical proficiency, engaging personality, writing skills, etc.). These should be easy to evaluate by asking a candidate a few simple questions.

- Make a list of questions for each trait and think about how you will score it on a scale of 1-5. You should have an idea of what will earn a “very weak” or “very strong” grade.

- Ask your questions and write down your grade for each trait.

- Add up the total score. Hire the candidate who has the highest score, even if your intuition says otherwise.

Ch. 22: Expert Intuition: When Can We Trust It?

- Acquiring Skill — Elite intuition (exhibited by outstanding chess players, basketball players, firemen, etc.) is developed by becoming extremely good at a certain collection of skills. When you’ve practiced something enough, the basics become second nature and you just “know” what to do without really thinking. You’re able to read the situation and intuitively know what to do because you’ve practiced the skills enough that you are elite at them. Many studies have shown that it takes 10,000 hours of dedicated practice to become elite at a skill.

- Ex. NBA Player — An NBA-level basketball player is so good that he doesn’t have to think about simple tasks like dribbling. He’s practiced and played so much that the simple parts of the game are second nature and he can read certain situations with ease. This gives him the ability to think about other, more complex parts of the game. The intuition he’s developed is linked to how many hours he’s put into his game.

- Quote (P. 238): “The acquisition of expertise in complex tasks such as high-level chess, professional basketball, or firefighting is intricate and slow because expertise in a domain is not a single skill but rather a large collection of miniskills.”

- Overconfidence — We are overconfident when the story in our mind comes easily and without any contradictions. A mind that follows WYSIATI will achieve confidence far too easily because it ignores what it does not know. Essentially, by purposely not factoring in other information and following our tendency for WYSIATI, we form a story that is based on limited information, which causes overconfidence. Just because someone is adamant that they are right doesn’t mean what they are saying is true — it just means they strongly believe the story in their mind, which may or may not be accurate.

- Skill and Feedback — Feedback is essential to developing a skill. It allows you to see what you did right or wrong and make adjustments if needed. If the feedback you receive while practicing a skill is quick and immediate, you are able to progress much faster than if the feedback is delayed. You can typically trust the intuition of experts who rely on a skill that involves immediate feedback. For people who are discussing a skill that does not feature immediate feedback, you should be skeptical of their intuition. There are some skills in a profession that feature instant feedback while other skills in the same profession have delayed feedback. Because we are able to develop strong intuition and skill in one area using instant feedback, we tend to assume and trust our intuition in other related skills that do not feature instant feedback. Watch out for this.

- Ex. Spanish — On a language learning app like Duolingo, you get immediate feedback while going through a lesson. You know immediately when you made an error, and it helps you correct course for the next time. This instant feedback accelerated your progress.

- Ex. Therapist — When it comes to evaluating a general treatment plan, therapists don’t receive instant feedback. They have to monitor the patients over a long period of time to find out if the treatment was effective or not. Because there’s a long delay, it’s harder to make progress when developing a treatment plan.

- Quote (P. 241): “Whether professionals have a chance to develop intuitive expertise depends essentially on the quality and speed of feedback, as well as on sufficient opportunity to practice.”

Ch. 23: The Outside View

- The Inside View — When personally involved in projects, we tend to favor the optimistic inside view (or best case scenario) when making predictions about the project. We assume we can get the project done faster and cheaper than what is really realistic. We tend to ignore how expensive and how long it took for other teams to complete a similar project. We also ignore some of the unforeseen roadblocks that could pop up along the way.

- The Outside View — The outside view provides a much more realistic look at a project. The outside view involves taking a step back and taking a hard, realistic look at how long a project might take, the costs that might be incurred, and the possible roadblocks that could occur along the way. Because we are personally involved in the project, we ignore the outside view. We much prefer the more optimistic inside view.

- Ex. Textbook — Kahneman and his team decided to write a psychology textbook for high school students in Israel. His team believed the project could be finished in 2 or 3 years. Somebody outside the team said it would take 7 years based on similar projects other teams have taken on in the past. Ultimately, it took the Kahneman’s team 8 years.

- Ex. Scottish Parliament Building — In 1997, a new Scottish Parliament building project was planned at an estimated cost of $40 million. The total project cost was $431 million by the time the building was up and running in 2004.

- Planning Fallacy — The term used to describe our tendency to take the optimistic inside view over the careful outside view when personally planning projects. The planning fallacy is a major problem with managers at workplaces around the country. Managers get personally excited about a project and become blind to realistic estimates of time and cost to complete the project. Employees under the manager are then left scrambling to complete the project on an unrealistic timeline.

- Quote (P. 252): “In its (the planning fallacy) grip, they (managers) make decisions based on delusional optimism rather than on a rational weighting of gains, losses, and probabilities. They overestimate benefits and underestimate costs. They spin scenarios of success while overlooking the potential for mistakes and miscalculations. As a result, they pursue initiatives that are unlikely to come in on budget or on time or to deliver the expected returns — or even to be completed.”

Ch. 24: The Engine of Capitalism

- Optimism — Many of the leaders, entrepreneurs, and CEOs in our world are optimistic people. They believe in themselves and their skills. They persevere through fear and obstacles. They take risks. They overcome challenges. People who are naturally optimistic can, however, sometimes believe in themselves too strongly, which can lead to bad decisions. They can sometimes be delusional about their chances at success when it comes to certain things. They sometimes overestimate their skills and underestimate the impact of other factors.

- Ex. Small Businesses — The chances of a small business surviving more than five years in the US is 35%. But a survey of American entrepreneurs found that young entrepreneurs estimate their chances of success at 60%. The young entrepreneurs are, in many cases, too optimistic, which leads to a bad decision to start a business that doesn’t have a great chance.

- Ex. Mergers and Acquisitions — People in the stock market almost always immediately sell the shares of the acquiring firm when a merger or acquisition is announced because the odds of the acquiring firm successfully taking on and managing a new firm on top of the existing one are fairly small. The managers are overconfident in their belief that they can take on the second firm.

- Quote (P. 255): “Most of us view the world as more benign than it really is, our own attributes as more favorable than they truly are, and the goals we adopt as more achievable than they are likely to be.”

- Competition Neglect — When we are overly optimistic, we tend to neglect the role of competition. We feel that our skills will be the only factor in how a project works out. The WYSIATI principle comes into play again — we only look at what we know, which is our skills and abilities. We ignore the competition. In reality, competition plays a big role in how things work out.

Ch. 25: Bernoulli's Errors

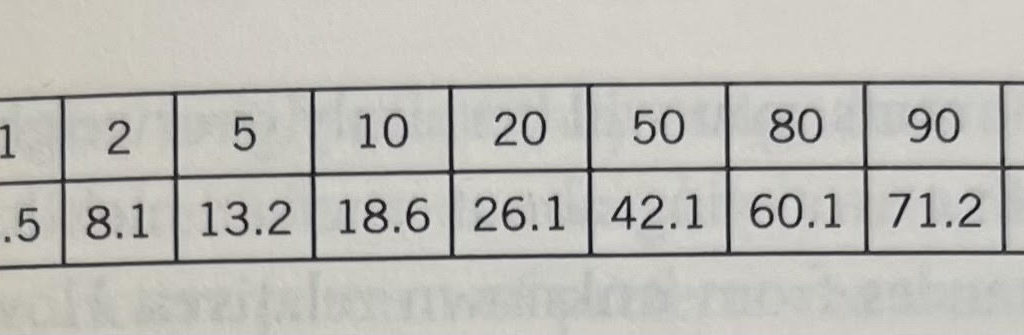

- Expected Utility Theory — An economics concept first discovered by a Swiss scientist named Daniel Bernoulli in 1738. Expected Utility Theory looks at the relationship between psychological value of money/desirability of money (utility). Bernoulli concluded that the psychological impact of money on your happiness decreases as you acquire more money. In other words, as you obtain more money, its psychological value on your happiness diminishes.

- Ex. $100 — If somebody with $0 was handed $100 as a gift, the person would be ecstatic. If somebody with $1,000,000 was handed $100, it wouldn’t have much of an impact.

- Ex. Raise — A person who is making $50k gets a raise to $65k. This person is pumped. A person who is making $300k gets the same $15 pay bump. This person is also excited, but far less excited than the person making $50k.

- Risk Aversion — Bernoulli also concluded that people are risk-averse and will almost always take the sure bet when possible rather than risk losing something. If offered a choice between a gamble and an amount equal to its expected value you will pick the sure thing.

- Bernoulli’s Errors — What Bernoulli failed to account for was reference points. This was a big hole in his thinking. Happiness levels are very much impacted by changes in wealth from a certain reference point. If Jack and Jill both have $5 million, but Jack had $1 yesterday and Jill had $9 million yesterday, Jack is MUCH happier than Jill today. Reference points and changes to the status quo matter a lot to our happiness, not just with money but with anything in life.

- Ex. Car — You were driving a Tesla, but needed to sell it and instead bought a Prius. The Tesla was the reference point. You are now much less happy about your vehicle situation, even though having any car is a great luxury.

- Ex. Salary — You are considering offering two candidates a job at a certain salary level. Candidate A currently makes more than Candidate B, but the new salary would be above both of their pay grades. Candidate A’s reference point is higher, so he will feel less utility (happiness/satisfaction) than Candidate B.

Ch. 26: Prospect Theory

- Prospect Theory — Developed by Kahneman and his colleague Amos Tversky, and one of the most important theories in psychology and economics. Prospect Theory is similar to Bernoulli’s Expected Utility Theory, but it accounts for reference points. Changes in wealth (gains and losses) are heavily factored in when evaluating the psychological impact of wealth — it’s not just about the amount of wealth, but the change in wealth. Prospect Theory has two main elements:

- Reference Points — Reference points matter to happiness when evaluating a change. The change from the status quo (the reference points) is a significant factor. The Jack and Jill example from the previous chapter is a great example — Jack is happier than Jill even though they both own $5 million because he gained wealth and Jill lost wealth to get to that number.

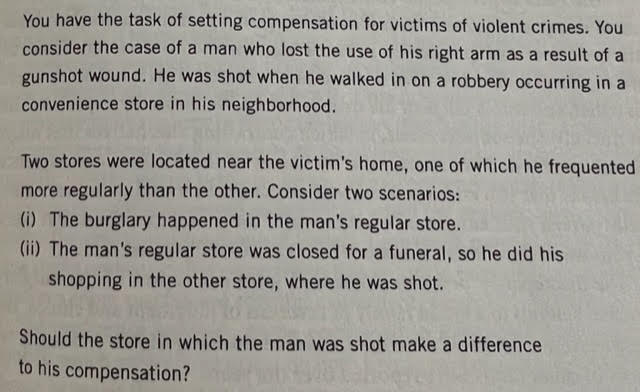

- Loss Aversion — Losses hurt about twice as much as gains make you feel good. We feel losses more significantly than we feel gains. We are all loss averse — we hate losing more than we like winning. The fact that we are loss averse helps explain why change can be difficult. We don’t like to lose people, situations, money, jobs, even if we are gaining something of moderately greater value. We feel losses more than we feel gains.

Ch. 27: The Endowment Effect

- The Endowment Effect — Closely related to loss aversion. We are very reluctant to give up things we already own — money, people, jobs, etc. This reluctance is due to loss aversion. Once you have something, you think of it as yours and giving it up would be a loss. The Endowment Effect and loss aversion are why changes can be really emotional and hard sometimes. When you change jobs, for example, the features of the new place are coded as pluses or minus relative to where you were. These disadvantages loom larger than advantages in this evaluation.

- Ex. Office Trading — If you have an office you like and are accustomed to, the thought of trading it with another person is met with a lot of reluctance. You “own” that office and trading it would feel like a big loss, even though you may be gaining an even better office by swapping. This is loss aversion and the Endowment Effect at work.

- Mugs Experiment — Richard Thaler and Kahneman used 22 students as subjects; 11 buyers and 11 sellers. Coffee mugs were given out to 11 of the 22 students at random. Economic theory predicts that there would be around 11 trades. In other words, about half of the sellers would be willing to sell freely in the open market if presented with a fair price by a buyer.

- Thaler and Kahneman were predicting a far fewer number of trades because they believed in the Endowment Effect, which states that losses hurt twice as much as gains and people don’t like to give things up.

- Because of this effect, Thaler and Kahneman predicted that the sellers would value their mugs at a much higher price than buyers, which would result in a low number of trades.

- The experiment was run 4 different times with the number of trades coming in at 4, 1, 2, and 2, respectively — all far fewer than 11.

- This was a landmark experiment in behavioral economics. It proved definitively that this effect was real.

Ch. 28: Bad Events

- Negative Focus — We tend to overly focus on bad or negative things. The tendency to fixate on the negative is a function of System 1, which gives priority to negative news over positive news. This is partly an evolution thing. To survive, early humans had to be on the lookout for negative “threats” in their world. Our mind is now literally programmed to recognize and prioritize the negative over the positive. The amygdala is considered the “threat center” of the brain and responds to negativity, which usually felt as fear.

- Marriage — John Gottman, a well-known marital relations expert, has said that the number of positive interactions has to outnumber negative interactions by a ratio of at least 5-1 for a marriage to survive.

- Negative Focus and Loss Aversion — Our tendency to overly focus on the negative contributes to loss aversion. We want to avoid the negative more than we want to gain something positive. This is why failing to achieve a goal (loss) stings more than it feels good to complete a goal (gain).

- Ex. Golf — Economists Devon Pope and Maurice Schweitzer analyzed more than 2.5 million putts from all distances made by professional golfers to test their hypothesis that pro golfers putt better for par than for birdie. This hypothesis came from loss aversion — both economists thought that golfers tried a little harder to avoid a loss (bogey) than to achieve a gain (birdie). By missing a birdie putt, the golfer is just missing out on a gain. By missing a par putt, the golfer is losing a stroke. Their findings backed up their hypothesis — the success rate on par putts exceeded the success rate on birdie putts by 3.6%.

- Quote (P. 304): “These fierce competitors certainly do not make a conscious decision to slack off on birdie putts, but their intense aversion to bogey apparently contributes to extra concentration on the task at hand.”

- Ex. Negotiations — The way things are in our lives currently is a reference point. Any changes from these reference points are perceived as gains or losses. We hate losses more than we like gains. In negotiations, many proposed changes appear to one side or the other as a loss. The side that is losing that “thing” in the negotiation feels it more than the other side feels it as a gain. This leads to unequal valuations, which is why it can be hard to come to an agreement on things when negotiating.

- Quote (P. 305): “Loss aversion is a powerful conservative force that favors minimal changes from the status quo in the lives of both institutions and individuals. This conservatism helps keep us stable in our neighborhood, our marriage, and our job; it is the gravitational force that holds our life together near the reference point.”

- Ex. Golf — Economists Devon Pope and Maurice Schweitzer analyzed more than 2.5 million putts from all distances made by professional golfers to test their hypothesis that pro golfers putt better for par than for birdie. This hypothesis came from loss aversion — both economists thought that golfers tried a little harder to avoid a loss (bogey) than to achieve a gain (birdie). By missing a birdie putt, the golfer is just missing out on a gain. By missing a par putt, the golfer is losing a stroke. Their findings backed up their hypothesis — the success rate on par putts exceeded the success rate on birdie putts by 3.6%.