Taxes For Dummies

Eric Tyson

GENRE: Business & Finance

GENRE: Business & Finance

PAGES: 640

PAGES: 640

COMPLETED: March 24, 2025

COMPLETED: March 24, 2025

RATING:

RATING:

Short Summary

The mere thought of taxes can make anyone feel overwhelmed, but it doesn’t have to be that way. In Taxes for Dummies, Eric Tyson and Margaret Munro break down the complexities of the tax code and deliver actionable financial strategies that can help readers reduce their tax bill.

Key Takeaways

Favorite Quote

“Retirement accounts really should be called tax-reduction accounts. . . . If you're a moderate-income earner, you probably pay about 25 to 30 percent in federal and state income taxes on your last dollars of income [based on your tax bracket]. Thus, with most of the retirement accounts described in this chapter, for every $1,000 you contribute to them, you save yourself about $250 to $300 in taxes in the year that you make the contribution. Contribute five times as much, or $5,000, and whack $1,250 to $1,500 off your tax bill!"

Ch. 1: Understanding the U.S. Tax System

- About the Book — Taxes for Dummies takes readers into the world of taxes. The book delivers a high-level overview of the tax code, strategies for reducing your tax bill, how to file your taxes, and more.

- About the Author — Eric Tyson is a best-selling author and former consultant to several large financial firms. He earned a bachelor’s degree in Economics and Biology from Yale and an MBA from Stanford.

- Taxes Everywhere — Taxes are everywhere. When you get paid at work, you pay federal, state, and local taxes. After you’ve paid taxes on your earnings, you get taxed on goods and services you buy. When you save and invest money (through retirement accounts, real estate, etc.), you get taxed for that as well. Over the course of your life, taxes are by far your largest expense. It pays to understand how to take deductions and reduce your tax bill.

- Brief History of Income Taxes — Federal income taxes haven’t always been around. In the early 20th century, people didn’t have federal income taxes to deal with. But in 1913, Congress established a system of federal income tax rates via the 16th Amendment to the Constitution. Prior to 1913, the majority of taxes collected by the federal government came from taxes on goods like liquor, tobacco, and imports. Today, personal income taxes, including taxes withdrawn from your checks for Social Security, account for 85% of the federal government’s revenue.

- Why Do We Pay Taxes? — The federal and state governments are sort of like a business; they spend huge gobs of money on things like defense, infrastructure, education, and healthcare, and therefore need to make money. The primary way these government bodies bring in money is by collecting taxes via taxes on income, goods, property, capital gains, and more. We essentially fund government spending by paying taxes.

- Incentivizing With Deductions — The federal government likes to incentivize certain behaviors — like home ownership, education, and charitable giving — by offering tax deductions. For example, the government generally likes when people buy and maintain houses. It’s good for people to own a home. As a result, there are several nice deductions that homeowners can take advantage of. Property tax deductions and mortgage interest deductions are examples. As a whole, the tax system offers opportunities to secure nice deductions. You just need to know what they are and how to leverage them.

- What Is Taxable Income? — Taxable income is different than the income you make from your job and your investments. Taxable income is the income you actually end up paying taxes on after applying deductions — it’s your income minus deductions. Using deductions and tax sheltering techniques, you can lower your taxable income. Some deductions are given to you automatically just for being a human being, such as the ‘standard deduction’. The standard deduction in 2023 was $13,850 for single filers, meaning these people were able to lower their taxable income by that amount simply for being alive. Head of households were able to take a $20,800 standard deduction and married couples filing jointly were able to take a $27,700 standard deduction. Other deductions available include things like mortgage interest and property taxes — although these are only beneficial if the total exceeds the standard deduction amount (you can’t deduct all of it).

- Quote (P. 12): “You need to note that your taxable income is different from the amount of money you earned during the tax year from employment and investments. Taxable income is defined as the amount of income on which you actually pay income taxes.”

- Quote (P. 12): “A second reason that you don’t pay taxes on all your income is that you get to subtract deductions from your income. Some deductions are available just for being a living, breathing human being. For tax year 2023, single people received an automatic $13,850 standard deduction, heads of household qualified for $20,800, and married couples filing jointly received $27,700. (People older than 65 and those who are blind get slightly higher deductions.) Other expenses, such as mortgage interest and property taxes, are deductible to the extent that your total itemized deductions exceed the standard deductions.”

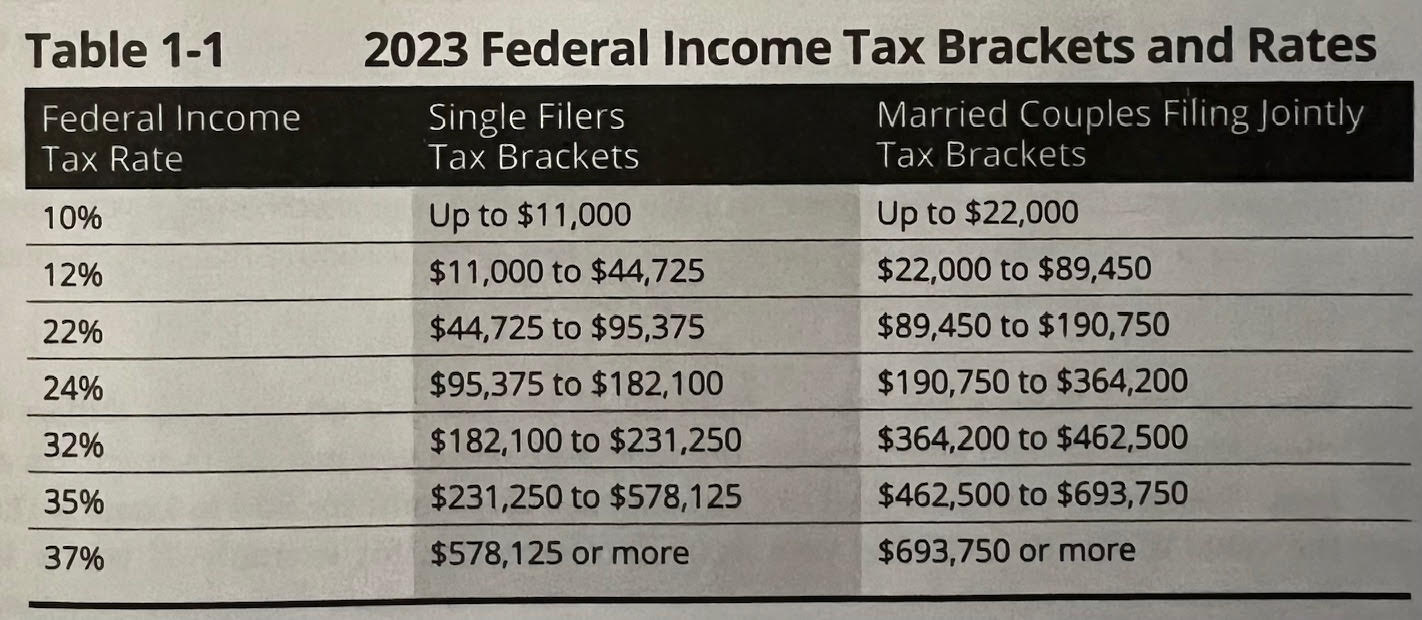

- What Is the Marginal Income Tax Bracket? — Everybody belongs somewhere in the federal income tax bracket. Where you fall depends on the amount of income you make. The system is arranged so that you pay a marginal tax rate where the more you make, the more taxes you’ll pay. Your marginal tax rate is the rate you pay on the last dollars you earn. So you essentially pay less tax on your first, or lowest, dollars of earnings and more on your last, or highest, dollars of earnings. Looking at the table below, if my total income for the year is $60,000, I will pay a federal tax rate of 10% on the first $11,000; 12% on the amount between $11,000-$44,725; and 22% on income from $44,725 up to $60,000. In essence, I would be paying a marginal federal tax rate of 22% on my last dollars of income — everything above $44,725. According to the IRS, the top 1% of income earners pay about 42% of all federal taxes. This is not counting state taxes. This is why it’s important to lower your taxable income if possible.

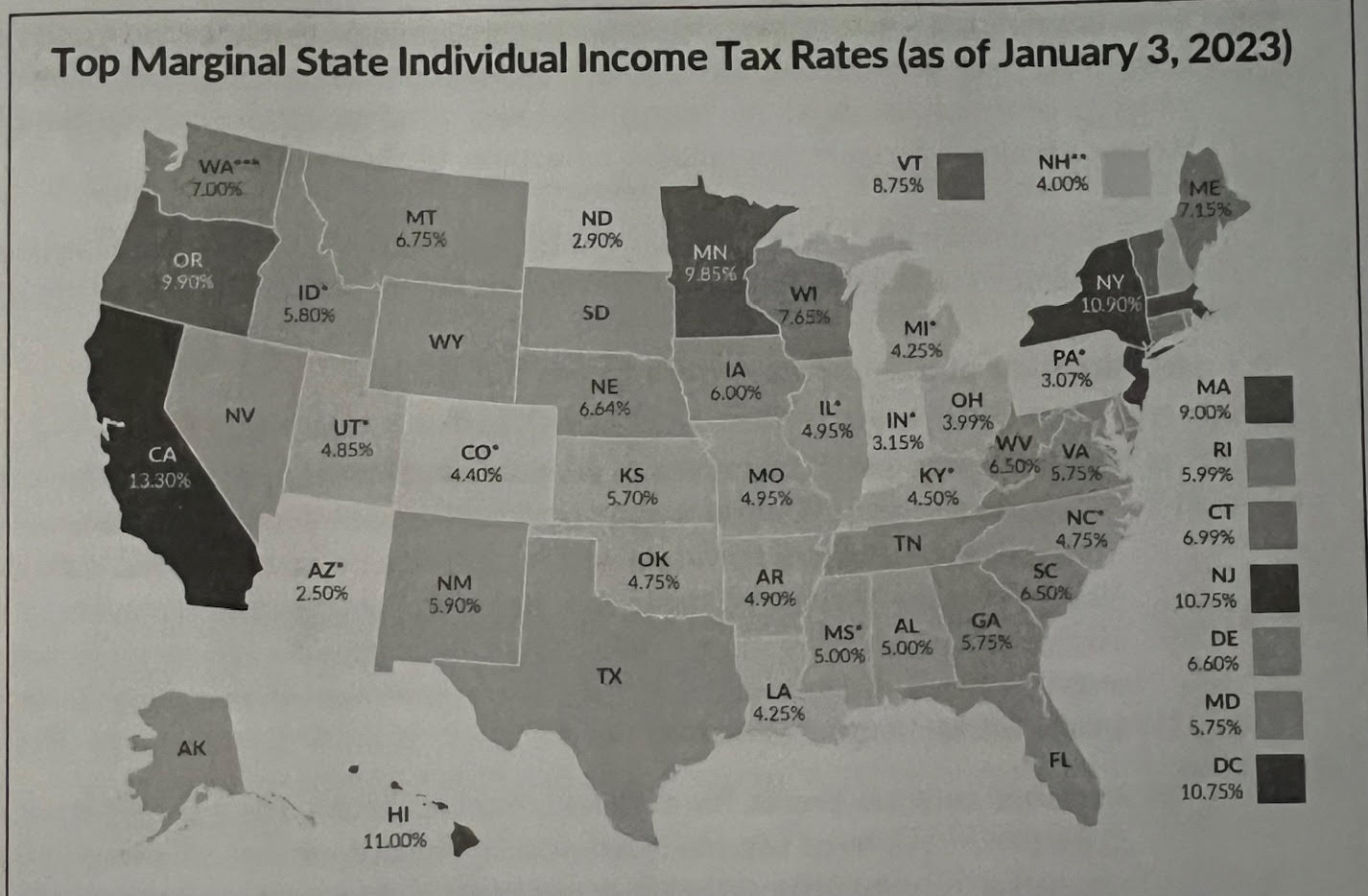

- State Income Taxes — You pay income taxes at the federal and state levels, unless you live in Florida, Nevada, Alaska, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, or Wyoming. These states don’t impose state income taxes. Every state has a different tax rate. Below is a graphic showing the different tax rates. Arizona has the lowest rate.

- What Is the Alternative Minimum Tax? — The AMT is a tax that was imposed on high income earners with high amounts of itemized deductions. Essentially, high earners were taking advantage of all the deductions available to them to significantly lower their taxable income. The government said, “not so fast!” and imposed the AMT in 1969 to ensure that high earners pay at least a minimum of taxes on their incomes.

- Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 — This bill did several things, but its biggest impact was lowering federal taxes rates. Looking at the table above, several of the marginal tax brackets were lowered by three or four percentage points. The higher brackets didn’t drop as much. This was beneficial for middle class and lower class people — these groups paid fewer taxes as a result. The bill also doubled the tax credit for parents of children. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was the largest tax code overhaul in three decades.

- Chapter Takeaway — Taxes are your largest lifetime expense. Everybody pays them, and it’s smart to learn strategies for reducing your taxable income using deductions and other adjustments. Everybody receives a ‘standard deduction’ for simply being alive.

Ch. 3: Getting and Staying Organized

- Keep Good Records! — You need to keep record of everything that you might use as a deduction to lower your taxable income, especially if you plan to itemize rather than take the standard deduction (which you would only do because you feel your itemized deductions will exceed the standard deduction). The IRS has up to three years to audit any of your tax filings. Below are common deductions where keeping receipts and records is critical in case of an IRS audit:

- Itemized Deductions — If you’re planning to itemize your deductions on Schedule A of your tax filing, you need to keep great records for the following possible deductions:

- Medical Expenses

- Mortgage Interest Payment

- Real Estate Taxes

- Personal Property Taxes

- State Income Taxes (up to $10k)

- Charitable Deductions

- Causality or Theft Loss

- Capital Losses (up to $3k)

- Dependent Expenses — If you plan to claim someone other than your qualifying child as a dependent, you need to be able to prove (if audited) that you provided more than 50% of that person’s total support. Keep your receipts.

- Car Expenses — You can take car expense deductions if you use your car for business reasons. But if you do, you better keep great track of everything, including miles, depreciation, and expenses like gas, insurance, and maintenance. Again, if the IRS comes knocking, you need to be able to prove that you reported accurate deductions.

- Home Expenses — Keep records of your mortgage interest and property tax payments. If you feel your itemized deductions will exceed the standard deduction, you can itemize these. Additionally, if you rent your house or use it for business purposes, keep records of taxes and expenses related to these purposes. They will come in handy if/when you use these to take deductions and lower your taxable income.

- Itemized Deductions — If you’re planning to itemize your deductions on Schedule A of your tax filing, you need to keep great records for the following possible deductions:

- Why Are Home Improvement Receipts Important? — Why is it so important to keep home improvement receipts? Because when you eventually sell your home, you can use these home improvements (and their receipts) to tell the IRS that the overall value of the house was more than whatever price you sold it for. You can even count things like closing costs, inspection fees, and other related expenses that went into buying the house (your “settlement statement” will have this info). Adding all of this stuff to the value of your home means you will have fewer capital gains to report and pay taxes on. For example, if I bought my house for $200,000 and sold it for $350,000 but I had $100,000 of home improvements, I can tell the IRS that the value of the house when I sold it was $300,000. This means I only owe capital gains taxes on $50,000 rather than $150,000. However, if I qualify for the primary residence exclusion, I won’t owe taxes on capital gains up to $250,000 if filing single and $500,000 if filing married jointly. In this case, I may not owe any capital gains tax at all on that $50,000 gain.

- Quote (P. 40): “The point of counting every tree and bush and other improvement to your home sweet home is to raise the basis, or total investment, that you have in your residence so that you can reduce your taxable profit when you sell.”

- Quote (P. 519): “Also, don’t forget to toss into your receipt folder the settlement statement, which you should have received in the blizzard of paperwork you signed when you bought your home. Don’t lose this valuable piece of paper, which itemizes many of the expenses associated with the purchase of your home. You can add many of these expenses to the original cost of the home and reduce your taxable profit when it comes time to sell. You also want to keep proof of other expenditures that the settlement statement may not document, such as inspection fees that you paid when buying your home.”

- Chapter Takeaway — Keep great records of everything, especially when planning to file itemized deductions to lower your taxable income. If something looks fishy, the IRS can audit you, and you will need to show proof.

Ch. 4: What Kind of Taxpayer Are You?

- Form 1040 — This is the form almost everyone completes to file their taxes. The form starts by asking you to report all of the basic income you made over the course of the year, including wages, interest, dividends from stocks, distributions from your retirement accounts (if any), Social Security benefits, and capital gains (or losses). After that, the fun and games begin with Schedule 1, Schedule 2, and Schedule 3. These forms ask you to report activity that is a little out of the norm. If you don’t have a very complex financial life, you probably won’t touch these. Below is a high-level overview:

- Schedule 1 — This is where you report things like income or losses from rental real estate, gambling income, and income from hobbies. The list of unusual forms of income that should be listed here is gigantic. For example, this is also where you list income from royalties, alimony, business income or losses, distributions from your HSA, jury duty pay, and much more.

- Schedule 2 — This is used to report additional taxes that aren’t included directly on the main Form 1040, such as Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), self-employment tax, and additional taxes on retirement distributions

- Schedule 3 — This is used to report certain tax credits that reduce your taxes, such as the Education Credits, and the Credit for Child and Dependent Care Expenses. The Child Tax Credit is a common example, though part of it is reported directly on Form 1040 instead of Schedule 3. Electric vehicle tax credits, like those Tesla previously offered were previously claimed through Schedule 3.

- Itemized Deduction vs. Standard Deduction — When filing your taxes, you generally have two options: take the standard deduction or choose to itemize your deductions. Both of these options allow you to reduce your taxable income. The standard deduction is a deduction everyone gets for being a living, breathing human. In 2023, it was $13,850 for single filers and $27,700 for married couples filing jointly. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act nearly doubled the standard deduction amounts across the board, making itemizing less common for most taxpayers. If you feel you qualify for a high number of deductions (e.g. mortgage interest and medical expenses) that, in total, would exceed the standard deduction, you can choose to itemize your deductions instead. Pick the strategy that lowers your taxable income the most. The lower your taxable income, the fewer taxes you will pay.

- Quote (P. 45): “Deductions are just that: You subtract them from your income before you calculate the tax you owe. (Deductions are good things!) To make everything more complicated, the IRS gives you two methods for determining the total of your deductions: itemized and standardized deductions. You get to pick the method that leads to the best solution for you — whichever way offers greater deductions. If you can itemize, you should, because it saves you tax dollars. The first method — taking the standard deduction — requires no thinking or calculations. For most people, taking the standard deduction is generally the better option. And the good news is that far more people now can and do claim the standard deduction because it was nearly doubled by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act which took effect in 2018. . . . If you are paying on a large mortgage, have high medical expenses, or give a substantial amount to charity, you may be better off itemizing your deductions.”

- Chapter Takeaway — Form 1040 is what everybody fills out to complete their taxes. Although most people won’t use Schedules 1, 2, and 3 of the form, they exist so you can report unusual forms of income and take advantage of tax credits. There are two main ways to file: take the standard deduction or itemize your deductions. Pick the one that will reduce your taxable income the most.

Ch. 5: All the Form 1040s

- Opening Page of Form 1040 — The opening page of Form 1040 is where you report all of your basic forms of income for the year. Weird, obscure, unusual forms of income like gambling income are reported on Schedule 1 of Form 1040, but the opening page is dedicated to all of the common forms of income. Below is a list of the lines on the opening page. This chapter contains full breakdown on all of these lines, including how to determine the amount you need to report. If you have money that needs to be inserted in these lines, you will usually be provided some kind of form that tells you the amount you need to type into these fields.

- Lines 1A-Z — W2 Income, Tips, Other Wages, Etc.

- Line 2A — Tax-Exempt Interest

- Line 2B — Taxable Interest Income (e.g. bond income)

- Line 3A — Qualified Dividends

- Line 3B — Ordinary Dividends Income

- Lines 4A and 4B — Total IRA Distributions

- Lines 5A and 5B — Total Pensions and Annuities

- Lines 6A and 6B — Social Security Benefits

- Line 7 — Capital Gain (or Loss)

- Line 8 — Other Income from Schedule 1

- Line 9 — Total Income (i.e. your total taxable income; the sum of lines 1-8)

Ch. 6: Form 1040 Schedule 1, Part I

- Schedule 1, Part I: Additional Income — Schedule 1, Part I is where you list all kinds of other, obscure forms of income you may have accumulated over the year that aren’t reported on the first page on your Form 1040. All kinds of weird forms of income appear here: alimony, gambling, jury duty pay, Olympic medals and prize money, foreign income . . . the list goes on and on. Once complete, you add everything together and transfer it to line 8 of Form 1040, and this offers you an updated look at your total taxable income. This chapter provides a line-by-line explanation of Schedule 1, Part I.

Ch. 7: Form 1040 Schedule 1, Part II: Adjustments to Income

- Form 1040 Schedule 1, Part II: Adjustments to Income — The second part of Schedule 1 is where you begin to file some of the deductions that can help lower your taxable income. These deductions are separate from itemized deductions and can be claimed even if you take the ‘standard deduction’. Once you’re done, you’ll add all of these deductions up and subtract the amount from your total taxable income that was found after completing Schedule 1, Part I. The deductions you can file in Schedule 1, Part II are wide-ranging and include things like educator expenses, Health Savings Account contributions, IRA contributions, student loan interest, and much more. There are a lot of rules that have to be met to qualify for these deductions, and this chapter outlines them by providing a line-by-line explanation of Schedule 1, Part II.

Ch. 8: Form 1040 Schedule 2: Additional Taxes

- Form 1040 Schedule 2: Additional Taxes — Form 1040 Schedule 2 is a special tax form for people who owe extra taxes that aren’t already included on their regular tax form (Form 1040). It has two parts: Part I is for certain taxes on income, like the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), which is an extra tax some higher earners have to pay. Part II is for other taxes, like self-employment tax (for people who work for themselves), taxes on early retirement account withdrawals, and household employment taxes (if you hire a nanny or housekeeper). If you have to pay any of these extra taxes, you add them up on Schedule 2 and include the total on your main tax form (Form 1040). Most people don’t need to complete this form.

Ch. 9: Form 1040 Schedule 3: Tax Credits

- Form 1040 Schedule 3: Tax Credits — Form 1040 Schedule 3 is where you can claim tax credits that lower your tax bill. Tax credits come in two types: refundable (which can result in a tax refund even if you don’t owe taxes) and nonrefundable (which can only reduce your tax bill to $0). Tax credits were put in place by Congress to encourage certain behaviors, like saving for retirement, adopting a child, or buying an electric vehicle. Credits are different than deductions, and they are probably more valuable than deductions. If you turn in your taxes and find that you owe money, credits allow you to lower the bill, dollar for dollar. On the other hand, deductions just lower your taxable income. There are all kinds of credits you can claim, and this chapter walks you through them by giving a line-by-line explanation of Schedule 3.

- Quote (P. 166): “Tax credits reduce your tax bill, dollar for dollar. There are credits on both your federal return and your state return, if you have one, so while we focus on the federal side, don’t ignore money that may be on the table from your state. Deductions, on the other hand, only reduce your taxable income. A $1,000 tax deduction reduces the tax for someone in the 24 percent federal income tax bracket by only $240. A $1,000 tax credit reduces that same person’s federal income tax by $1,000.”

- Common Tax Credits — There are a good amount of refundable and nonrefundable tax credits you can claim. Again, the government put these in place in order to encourage certain behaviors that seem to be good for society and the economy as a whole. It’s important to note that most tax credits are limited by income restrictions. In other words, if you exceed certain income thresholds, the credit begins to phase out. Below are some of the most common tax credits people claim:

- Foreign Tax Credit — If you paid taxes to another country, you may get a credit to avoid double taxation

- Child and Dependent Care Credit — You can claim a credit if you use childcare or dependent care so you can work at your job. This includes things like babysitters, nursery school, summer day camps, after-school programs, and daycare expenses. You can potentially claim both federal and state tax credits for child and dependent care, so it’s worth looking into.

- Education Credits — Credits like the American Opportunity Credit and Lifetime Learning Credit help encourage people to go to school by allowing you to offset the cost of higher education

- Retirement Savings Contributions Credit (Saver’s Credit) — Encourages low-and moderate-income taxpayers to save for retirement

- Residential Energy Credits – You can claim a tax credit for installing energy-efficient home improvements (e.g., solar panels, energy-efficient windows)

- Electric Vehicle (EV) Credit – Available for purchasing a qualifying electric or plug-in hybrid vehicle. This is a refundable tax credit.

- Adoption Credit — The adoption process is long and expensive. This credit allows you to lower your tax bill if you adopted a child.

- Earned Income Credit (EIC) — This is a refundable tax credit designed to help low/moderate income workers by reducing their tax bill or increasing their refund. The amount of the credit depends on earned income, filing status, and the number of qualifying children. Generally speaking, your earned income (i.e. from wages, tips, self-employment, etc.) has to be very low to qualify for this — and if you make more than $11,000 in investment income (as of 2023), you won’t be eligible.

Ch. 10: Finishing Up the 1040

- Finishing Form 1040 — This chapter takes you through the final few lines of Form 1040, where you determine your taxable income, total tax bill, and whether you owe money or get a refund. First, you’ll find your Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) — this is your total income after certain adjustments but before deductions are applied. Next, you subtract the standard deduction or itemized deductions (whichever approach you decide to use) to get your taxable income, which is the amount the IRS actually uses to calculate your tax bill. Once your total tax bill is determined, you compare it to the amount of tax you already paid throughout the year (via paycheck withholdings). If you underpaid, you owe the IRS the difference. If you overpaid, you get a tax refund for the extra amount.

Ch. 11: Itemized Deductions — Schedule A

- Schedule A: Itemized Deductions — As you fill out your Form 1040, there are opportunities to complete supplemental Schedules A, B, C, D, and E and other forms. Some of these aren’t necessary to complete — it all just depends on your situation and what happened to you throughout the year. Schedule A is available to anybody who believes their itemized deductions would exceed the “standard deduction.” Either the standard deduction or the total of all itemized deductions is then transferred to Form 1040 and subtracted from your total taxable income to determine your tax bill. Again, the standard deduction is what everybody can take; it’s the deduction you get for simply being a human. In 2023, it was $13,850 for single filers, but there are also amounts for different filing statuses (e.g. married, filing jointly). On Schedule A, you can itemize several key deductions, including:

- Medical & Dental Expenses — Your total medical and dental expenses (not including what your employer covers through your health plan at work) must exceed 7.5% of your AGI (line 11 of your Form 1040). This detail knocks many people out of contention for this deduction. If you qualify for this deduction, it probably means you had a serious health issue. It’s a good thing if you can leave this section blank.

- Taxes You Paid — You can deduct various taxes you’ve paid throughout the year, such as state or local income taxes that are withdrawn from your paycheck throughout the year (box 17 on your W2), sales tax accumulated during the year (adding up all your receipts from the year — this might be beneficial if you made a big purchase, like a car), real estate taxes (e.g. when you buy or sell a home; find this number on Form 1099-S), and property taxes (e.g. annual property taxes on your home). Federal income taxes and Social Security taxes cannot be deducted. Everything you deduct in this category cannot exceed $10,000, and you can’t deduct both state income tax and sales tax — it’s one or the other.

- Interest You Paid — The IRS allows you to deduct interest on certain types of loans, notably mortgages used to buy your primary and secondary home. Interest incurred for consumer debt (e.g. credit card debt and auto loans) cannot be deducted. Regarding mortgages, the interest can be deducted as long as your loans don’t combine to exceed $750,000 and the homes themselves are listed as the collateral for a default. You can also deduct interest on loans you take out for home improvement projects. You can even deduct interest that you pay on a home equity loan or line of credit — the key is that the money must be used solely for the purpose of the home, not for some other reason such as buying some groceries. If you used the money to buy groceries, for example, the interest on the loan would not be tax deductible. You can find the mortgage interest you paid during the year listed in Form 1098, which is sent to you by your mortgage lender. If you didn’t pay more than $600 in mortgage interest, this form will not be sent to you and you’ll need to ask for it.

- Quote (P. 215): “It doesn’t matter whether the loan on which you’re paying interest is a mortgage, a second mortgage, a line of credit, or a home equity loan. The interest is deductible as long as your homes serve as collateral for the loan, and provided that the money lent to you is used solely for the purpose of either purchasing a home, refinancing an existing mortgage, or paying for improvements to that home.”

- Gifts to Charity — You can deduct your gifts to charity, whether they were made by cash or check or a physical donation (e.g. giving clothes to Goodwill). The key is to keep your receipts so you can prove that you made donations. For a cash or check donation to count, the charity must be a “qualified 501(c)(3) organization,” meaning it has been registered with the IRS. Interestingly, you can also deduct out-of-pocket expenses incurred while doing volunteer work for a charity. For example, you can deduct expenses for things like gas, parking fees, tolls, and even the upkeep of a uniform.

Ch. 12: Interest and Dividend Income — Schedule B

- Schedule B: Interest & Dividend Income — As you fill out Form 1040, you must complete Schedule B if you accumulated more than $1,500 of interest or dividend income, have a foreign bank account, or received interest/income from foreign sources, even if the total is under $1,500. Don’t overlook the foreign income/dividends from foreign sources — many people invest in global mutual funds that receive dividends from foreign sources. What you need to complete Schedule B are the various 1099 forms that are sent to you as needed (1099-INT, 1099-DIV, and 1099-OID). This chapter takes you through Schedule B, line by line.

Ch. 13: Business Tax Schedules — Schedules C and F

- Schedule C: Business Tax — As you fill out Form 1040, you need to complete Schedule C if you run your own business as a sole proprietor or single-member LLC. Schedule C is where you’re asked to report income, expenses, net operating profit (or loss), and deductions for business-related things like travel and meals, entertainment, utilities, supplies, office space, and more. The point of this schedule is for the IRS to determine how much income you made from your business so they can levy the proper amount of income tax and self-employment tax. Interestingly, if, after all deductions are accounted for, you report a net operating loss on your business, you can use that loss to reduce your taxable income from your other job (like your W2 job). Owners of rental property generally use Schedule E instead of Schedule C, unless they provide substantial services beyond basic landlord duties (such as daily housekeeping or meals), in which case Schedule C may apply. If you don’t operate your own business, you don’t need to bother with Schedule C. Below are some deductions you can take if you run your own business:

- Depreciation

- Car Expenses

- Travel, Meal, and Entertainment

- Utilities

- Supplies

- Office Space

Ch. 14: Capital Gains and Losses — Schedule D

- Schedule D: Capital Gains & Losses — If you sell something like a stock, bond, ETF, or mutual fund for more than you paid for it, you’ve just produced a capital gain, and you’ll have to pay tax on it. Conversely, if you sell the asset for less than you paid for it, you’ve produced a capital loss, which is tax deductible and can be used to reduce your taxable income. Schedule D is where you report capital gains and capital losses. “Assets” aren’t limited to stocks; selling jewelry, baseball cards, and houses also applies here. Schedule D is broken into two parts: Part I is where you report short-term capital gains and losses (assets held for 12 months or less), and Part II covers long-term capital gains and losses (assets held for 12 months or more). Long-term capital gains are taxed at a lower rate than short-term capital gains, which is why you should always aim to hold assets for at least 12 months. For example, most people will only owe a 15% tax on capital gains from stocks they’ve held for more than a year, rather than paying their ordinary income tax rate, which is usually higher than 15%.

- Where Do You Get the Info? — To complete Schedule D, you’ll need some information. If you’ve sold stocks throughout the year, your broker will send you Form 1099-B; the information on it will help you complete Schedule D. If you sell your house, you will receive a closing statement, and this sheet can help you report your taxable gain (if you even need to report it).

- Home Improvement Projects: Keep Your Receipts! — I have notes about this in an earlier chapter, but it’s important. Keep any receipts associated with home improvement projects! This will allow you to reduce the amount of capital gains tax you owe when you eventually sell the house. How? Home improvement projects increase the value of your home. So, if you bought your house for $300,000 but put $100,000 into it through home improvement projects, you can tell the IRS that the value of the home at the time of sale was really $400,000. If you sold the house for $600,000, that means you theoretically only have to pay capital gains taxes on $200,000 instead of $300,000. Of course, this is all a moot point because there’s a primary residence exclusion that says you don’t have to pay any capital gains taxes on the sale of your primary residence if the gain is $250,000 or less for singles and $500,000 or less for married couples and if you’ve lived in it for at least two of the last five years. But you get the point! Keep the receipts.

- Primary Residence Exclusion — As mentioned in the bullet above, there’s a sweet exclusion that allows you to avoid paying any capital gains taxes on the sale of your primary residence if you’ve lived in the home for at least two of the last five years and the capital gain was less than $250,000 for singles and $500,000 for married couples filing jointly. This is one of the best remaining tax breaks in the system. If you make more than those amounts on the sale of your home, you will have to pay capital gains taxes but only on the amount above the $250,000/$500,000 threshold. Alternatively, if you have a capital gain above the $250,000/$500,000 mark, you could hold the property until your death — when you do this, the person who inherits the home will not owe any capital gains tax if they sell it. Weirdly, if you sell your house for a loss, you’re not able to use it to offset other capital gains or lower your taxable income like you are with stocks.

- Capital Losses From Stocks — If you sell stocks or other investments at a loss, you can use those capital losses to offset any capital gains you made in the same year. For example, if you had a $5,000 capital loss and a $3,000 capital gain, you could use the loss to basically cancel out the gain, leaving you with no taxable capital gain and an extra $2,000 loss remaining. If your capital losses exceed your capital gains (like in this example), you can use up to $3,000 per year to offset other taxable income, such as wages from a W-2 job. Any losses beyond this $3,000 limit can be carried forward to future tax years to offset gains or income later. So, in this example above, that additional $2,000 left over after erasing the taxes on the $3,000 capital gain can then be used to help offset your taxable income you made from your “normal” job.

Ch. 15: Supplemental Income and Loss — Schedule E

- Schedule E: Supplemental Income & Loss — Schedule E is where you report your income (or loss) from your rental properties, royalties, partnerships, S Corporations (i.e. corporations that don’t pay taxes; the owners report the corporation’s income or loss on their personal tax return), trusts, and estates. Page 1 of Schedule E is where you report your rental property information. The page is laid out in the format of an income statement, allowing you to list out income and expenses down the page.

- Reporting Rental Property Income & Expenses — If, after subtracting expenses from income on Page 1 of Schedule E, you have a positive number, you have to pay taxes on that amount. If you have a negative number (a loss), you can use up to $25,000 in rental losses to lower your taxable income from your W-2 job. Lines 3-4 are where you list your income from rental properties. This is essentially the rent that you received throughout the year. You can find this number on your 1099-NEC or 1099-K. Lines 5-19 are where you list all of the various expenses (i.e. deductions) that went into the rental property. These can be used to offset your rental income, allowing you to pay little to no tax on that income. If your expenses outweigh your rental income, you have a loss that can be used to lower your taxable income from your W-2 job. This opportunity to deduct all the expenses that went into your rental property is one of the major advantages of real estate investing. Below are some of the things you can deduct on Schedule E:

- Advertising / Marketing — You can deduct the cost of ads, whether they’re placed in your local newspaper or placed on the Internet via something like Google Ads

- Auto / Travel — If you travel to your rental property for maintenance, inspections, or tenant meetings, you can deduct mileage, airfare, lodging, and other travel expenses

- Cleaning / Maintenance — Expenses for professional cleaning services, landscaping, pest control, and general upkeep of the property are deductible

- Commissions — If you pay a real estate agent or a leasing service to find tenants for you, their commission fees are deductible

- Property Insurance Policy — The cost of your rental property’s insurance policy, including landlord insurance, is fully deductible

- Property Management Fees — If you hire a property manager, their fees are deductible

- Home Mortgage Interest — The interest you pay on the property’s mortgage is deductible

- Repairs — Necessary repairs like fixing a leaky roof, replacing a broken appliance, or patching drywall are deductible in the year they’re completed

- Supplies — Items used for maintenance and repairs, such as tools, paint, and light bulbs, can be deducted as necessary business expenses

- Taxes — Property taxes are deductible

- Utilities — If you pay for utilities like water, electricity, gas, or trash collection instead of the tenant, you can deduct these costs

- Building Depreciation — You can deduct depreciation of the house using a 27.5-year scale

- What Happens If You Have a Rental Loss? — What happens if, after you subtract expenses (i.e. deductions) from rental income, you end up with a loss on paper? For most people, you can use up to $25,000 in rental losses to lower your taxable income on other sources of income, like your income from your W-2 job. As I’ve read in other books, this tax advantage is one of the major advantages to real estate investing. There are some limitations here, however. To qualify for this, you must be an active participant in managing the rental property and your modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) must be $100,000 or less. This deduction begins to phase out after $100,000. If your income exceeds $150,000, you typically cannot deduct rental losses against other income unless you qualify as a real estate professional. If you make more than $150,000, your rental losses will carry forward to offset rental income in future years instead of reducing W-2 income.

- Schedule E: Page 2: Page 2 of Schedule E is where you report income from partnerships, S Corporations, estates, and trusts. Partnerships and S Corporations are called pass-through entities because all of the income and deductions from these pass through to each partner or shareholder based on ownership percentage. These partners and shareholders then report the income and deductions here on their personal tax forms here on Schedule E. This is a fairly difficult form to complete. Below are the two main benefits of investing in these pass-through entities:

- Avoids Double Taxation — Unlike C corporations, which pay corporate income tax and then tax shareholders again on dividends, pass-through entities only tax income once (at the individual level)

- Deductions & Losses Flow Through —Investors can deduct their proportionate share of business expenses and potential losses on their personal tax returns, which, for most people, basically reduces their taxable income

- Schedule E: Trusts & Estates — Part III of Schedule E is where you report income or loss from an estate or trust of which you are a beneficiary. Think interest from bonds and dividends and capital gains from stocks. Capital gains from property owned by the estate or trust are also included here. You will receive this information on Schedule K-1, which outlines your share of the estate or trust’s income, deductions, and credits. Capital gains from assets sold by the estate or trust are usually taxed at the estate or trust level, meaning they are not always passed through to beneficiaries. However, if the trust distributes capital gains, they may appear on your K-1 and be reported on Part III of Schedule E.

Ch. 17: Other Schedules and Forms to File

- How Taxes Work: Pay as You Go — Most people think the tax system is a pay-at-the-end-of-the-year one where taxes are due on April 15, but it’s not. The tax system is really a pay-as-you-go system. That’s why, as a W-2 worker, you have money withheld from every paycheck for things like federal taxes, Social Security, Medicare, and state taxes. You don’t even have to think about paying your taxes; they are automatically withheld from your paycheck and paid for you by your employer. You pay as you go. Self-employed people, on the other hand, usually don’t have taxes withheld from their paychecks, so they have to send quarterly tax payments to the government instead. They do this by completing something called Form 1040-ES. Because our tax system is a pay-as-you-go system, not making quarterly payments as a self-employed person, or someone making income that isn’t subject to withholding, will lead to hefty fines and penalties.

- Quote (P. 361): “The U.S. tax system actually has a simple rule that most people never think about: It’s a pay-as-you-owe system, not a pay-at-the-end-of-the-year one. That’s why withholdings (having your taxes deducted from your paycheck and sent directly to the government) are great — what you don’t see, you don’t miss, and your tax payments are made for you. If you’re self-employed or have taxable income, such as retirement benefits, that isn’t subject to withholding, you need to be making quarterly estimated tax payments, either by filing paper forms with Form 1040-ES, or paying electronically through the IRS website.”

- Quote (P. 448): “If you’re self-employed or earn significant taxable income from investments outside retirement accounts, you need to be making estimated quarterly tax payments.”

- Paying Quarterly Taxes: The Safe Harbor Method — If you are self-employed and not withholding taxes from your paychecks, probably the best way to estimate your quarterly tax payments is by using the Safe Harbor method, where you pay whatever your taxes were last year in quarterly payments. For example, if you paid $3,000 in taxes last year, you would send quarterly tax payments of $750 to the government. Then, in April, you file your Form 1040 and pay whatever the difference is. If you incurred more taxes than last year, you’ll owe some money. If you incurred fewer taxes than last year, you’ll get a refund. The Safe Harbor method offers a simple way for self-employed people to make their tax payments throughout the year while avoiding fines and penalties.

- Other Tax Forms — There are seemingly an endless number of tax forms you may or may not need to file. Everything depends on your life and what’s going on in it. Some people will need to file certain tax forms with their Form 1040, while others won’t even need to glance at them. Below are some interesting ones to keep in mind:

- Form 3903: Moving Expenses — Prior to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, most people could deduct a lot of the expenses they incurred while moving to another city. Now, this isn’t as much of a factor for most people. Active-duty military members moving due to military orders are the ones who get the most of this opportunity now.

- Form 8606: Nondeductible IRAs — If you put money into a Traditional IRA using money you already paid taxes on, you need to tell the government so they don’t make you pay taxes on it again later. This form keeps track of that. It also helps if you switch your savings from one type of account to another, like moving money into a Roth IRA. Nondeductible contributions to a Traditional IRA in your brokerage account are more common than you think. Why? Because if you are enrolled in a company retirement plan (e.g. a 401k) and your Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) exceeds a certain level ($73,000 for a single filer in 2023), your contributions into the account cannot be used to lower your taxable income. In other words, the contributions are not tax deductible, meaning you will have already paid taxes on that money before you contributed it into the account.

- Form 8615 & 8814: Kiddie Tax — If you have a child under the age of 19, or under age 24 if they’re a full-time student providing 50% or less of their own support, all investment income(e.g. dividends from stocks or interest from bonds) they make that is more than $2,500 is taxed at the parents’ tax rate. The reason for this rule is to remove the temptation of higher-income earners to transfer lots of money to their kids just to save tax dollars by having their kids invest the money and pay fewer taxes on it since the kids are in a lower tax bracket. The quote below offers a closer look at how the kiddie tax works.

- Quote (P. 370): “Here’s how the kiddie tax works. If a child has $3,000 in investment income, for example, the first $1,250 is exempt from tax. The next $1,250 is taxed at the child’s tax rate. The remaining $500 is taxed at the parent’s federal income tax rate.”

- Form 8829: Expenses for Business Use of Your Home — You can claim a home office deduction if you have a dedicated space in your house that you use for your business, even if it’s used only to conduct administrative or management activities of your business, provided you have no other office or other place of business where you can perform the same tasks. For example, Dad, as an independent real estate agent without an office at Caldwell Bank, is claiming a home office deduction on his tax return this year. This opportunity allows you to deduct the mortgage interest, real estate taxes, depreciation, home insurance, utilities, and repairs related to that part of your house. You basically add up all of the expenses and divide it by the office’s square footage. See this chapter for more info.

- Schedule H: Household Employment Taxes — If you have household workers (including housekeepers, babysitters, landscapers, and nannies), who earned more than $2,600 from you in 2023, you might be required to pay employment taxes (e.g. the employer’s half of Social Security and Medicare taxes) for them. In this case, you are considered their employer, meaning you’re responsible for withholding and paying certain taxes on their behalf. This rule, commonly known as the “nanny tax,” applies to household employees but not to independent contractors. In other words, if you are keeping up your yard by paying a landscaping company that sends out one of their employees, this would not apply to you. An example would be if you paid more than $2,600 during the year to a family friend to babysit your kid.

- Claim Your Depreciation! — If you are eligible to deduct depreciation of your house on your tax return (e.g. if you own a rental property or can take a home office deduction), do it! When you sell the property, the IRS requires “depreciation recapture,” meaning you must pay taxes on the depreciation you were allowed to take — whether or not you actually claimed it. Since you’ll owe taxes on that amount anyway, it would be foolish not to claim it on your tax return if you have the chance to do so.

- Quote (P. 375): “Many people avoid taking depreciation on their homes for a variety of reasons. Some may not understand how depreciation works. For others, the idea of trying to figure out their home’s adjusted basis leaves them flustered. Yet others think that, if they depreciate now, they’ll have a hard time calculating their gain or loss on the sale of that home down the road. What you may fail to realize is that the IRS deems that the value of your home has depreciated whether or not you deduct the depreciation to which you’re entitled. When you go to sell that home, you’re required to recapture that depreciation, even if you didn’t actually take the deduction as part of your home office deductions on your tax return.”

Ch. 22: Trimming Taxes With Retirement Accounts

- Retirement Accounts: Tax Sheltering Vehicles — Saving and investing through retirement accounts is one of the simplest and best ways to reduce your taxes. Why? These accounts — whether it’s a Traditional IRA in your brokerage account or a retirement account offered at work, like a Traditional 401k — help you lower the taxable income you report to the IRS by allowing you to contribute pre-tax income. The pre-tax contributions reduce your taxable income, then grow tax-deferred in the account. You will still have to pay taxes on both the contributions and growth of the money when you withdraw, but the idea is that you’ll be in a much lower ordinary income tax bracket when you’re older and in retirement. The only income you’ll likely be making is through dividends and stocks, passive investments like real estate, Social Security, and withdrawals from retirement accounts. In other words, you’ll be making much less income than you did while working. See the quote below for an example of how all of this works.

- Quote (P. 459): “Retirement accounts really should be called tax-reduction accounts. . . . If you’re a moderate-income earner, you probably pay about 25 to 30 percent in federal and state income taxes on your last dollars of income [based on your tax bracket]. Thus, with most of the retirement accounts described in this chapter, for every $1,000 you contribute to them, you save yourself about $250 to $300 in taxes in the year that you make the contribution. Contribute five times as much, or $5,000, and whack $1,250 to $1,500 off your tax bill!”

- Quote (P. 460): “And remember this: You may get an added bonus from deferring taxes on your retirement account assets if you’re in a lower tax bracket when you withdraw the money. You may well be in a lower tax bracket in retirement because most people have less income when they’re not working.”

- Retirement Accounts: Early Withdrawals — If you withdraw money from your Traditional IRA before the minimum age (at this time 59.5-years-old), you will have to pay income taxes and an early withdrawal penalty of 10%. The penalty is in place for good reason — to discourage people from withdrawing early. If you could easily tap these accounts without penalties, people likely wouldn’t have much left in the account by the time they retired. There are exceptions for emergencies like catastrophic medical expenses or disability. You can also withdraw without penalties for a first-time home purchase (up to $10,000) and for qualified higher educational costs.

- Types of Retirement Accounts — There are a wide variety of retirement accounts available, both through an employer and in a standard account held with a brokerage firm like Fidelity. Below are a few of the most common:

- Employer-Sponsored Plans

- Traditional 401(k) — For-profit companies generally offer 401(k) plans. With a Traditional 401(k), you are using pre-tax dollars to fund the account. This allows you to lower your taxable income, and the account grows tax-deferred. The idea is that, when you withdraw in retirement, you will be in a much lower income bracket. The max contribution in 2023 was $22,500. Most companies offer a percentage match, which is basically free money. Always contribute at least whatever the matching percentage is.

- Roth 401(k) — The Roth 401(k) is funded with after-tax dollars, and the account (contributions and any growth in the account) can be withdrawn tax-free once you’ve met the minimum age requirement. Because after-tax dollars are used, the contributions are not tax deductible.

- 403(b) — Many nonprofit organizations offer 403(b) plans. Like a Traditional 401(k), contributions to these plans are tax deductible (i.e. can be used to lower taxable income).

- SIMPLE Plans — These are mostly used by small businesses

- Self-Employed Plans

- SEP-IRAs — Your contributions to a SEP-IRA as a self-employed person are deducted from your taxable income. You can contribute up to $66,000 to this account (as of 2023).

- Defined-Benefit Plans — These plans are for people who are able and willing to put away more than the SEP-IRA contribution limit of $66,000 per year. Of course, only a small percentage of people can afford to do this. Therefore, this type of plan is usually available to very high earners.

- Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs)

- Tradition IRA — A Traditional IRA works similar to a Traditional 401(k): The money in the account is pre-tax dollars and it grows tax-deferred. Contributions to the account can be tax deductible for some people. If you are enrolled in a retirement plan at work and you exceed certain Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) thresholds ($73,000 for single filers in 2023), your contributions are not tax deductible. This is a major downer, and it’s not an issue with 401(k)s — all contributions to 401(k)s are tax deductible. You can still make “nondeductible” contributions to your Traditional IRA that won’t lower your taxable income and will grow tax-deferred, but it doesn’t make a lot of sense to do so. The maximum you could contribute to a Traditional IRA in 2024 was $7,000. Required distributions begin at age 73.

- Roth IRAs — The Roth IRA operates like a Roth 401(k): Contributions are made with after-tax dollars, and everything in the account can be withdrawn completely tax-free once you’ve met the minimum age requirement. This is one of the best wealth-building tools available. The ability to withdraw all money in the account tax free is a huge advantage. In 2024, the maximum annual contribution was $7,000. If your Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) is less than $125,000 for single filers and $198,000 for couples, you can contribute the maximum to your Roth IRA. If you make more than those amounts, you slowly begin to get phased out. If you make enough income to be phased out of the Roth IRA, consider contributing more to your Roth 401(k) to make up for it — you can contribute up to $22,500 annually to a Roth 401(k). Unlike Traditional IRAs, there is no required distribution age with Roth IRAs because after-tax dollars were used to fund the account.

- Employer-Sponsored Plans

- What Are Annuities? — Annuities are investment products — contracts, actually — that insurance companies back. If you, the annuity holder (investor), die during the “accumulation phase” prior to receiving payouts from the annuity, your designated beneficiary is guaranteed to receive the amount of your original investment. Annuities are mostly for people who aren’t very good at saving and managing their money. If you’re going to invest in one, which you probably shouldn’t, you should plan to leave the money in it for at least 15-20 years. The reason for this is that annuities carry high fees because of the insurance that comes with them (the insurance that allows the annuity to go to your spouse if you die). It will take some long-term growth in the account to offset those high fees.

- 401(k) Rollovers — What happens to your 401(k) when you leave your employer? You generally have the option of leaving your money in the employer’s plan or transferring it to an IRA at an investment company of your choice (e.g. Fidelity). The process of moving the money from an employer plan to your IRA is called a rollover. When doing a rollover, never take personal possession of the money! If you are given the money, the employer must withhold 20% of it for taxes. Instead, you want it to transfer directly to your IRA account. This is fairly easy to arrange.

- Quote (P. 471): “When you roll money over from an employer-based retirement plan, don’t take personal possession of the money. If your employer gives the money to you, the employer must withhold 20 percent of it for taxes. This situation creates a tax nightmare for you because you must then jump through more hoops when you file your return.”

Ch. 23: Small Business Tax Planning

- The Different Business Entities — When starting a business, choosing the right entity is important because it affects taxes, liability, and how profits are distributed. The five main types of business structures are C Corporations, Sole Proprietorships, Partnerships, Limited Liability Companies (LLCs), and S Corporations. Each has unique advantages and drawbacks. Below is a breakdown:

- C-Corp — A separate legal entity that pays its own corporate taxes and can have unlimited shareholders. Profits are taxed twice — once at the corporate level and again when distributed as dividends to shareholders.

- Sole Proprietorship — The simplest business structure, where the owner and business are legally the same. Profits and losses are reported on the owner’s personal tax return, but the owner has unlimited liability for business debts, meaning they can lose all of their personal assets if sued.

- Partnership — A business owned by two or more people who share profits, losses, and liability. Partnerships can be general (equal responsibility) or limited (some partners only invest but don’t manage the business).

- LLC — A hybrid structure that combines the liability protection of a corporation (i.e. can’t be sued for everything you’re worth) with the tax benefits of a sole proprietorship or partnership (i.e. profits and losses typically pass through to the owner’s personal tax return on Schedule C but owners can also choose to be taxed as corporations if they want).

- S-Corp — A special type of corporation that avoids double taxation by passing income and losses to shareholders’ personal tax returns

- How Small Businesses Are Structured —Most small businesses are not structured as traditional C-Corporations. Instead, they operate as sole proprietorships, LLCs, partnerships, or S Corporations, which are considered pass-through entities because their profits or losses pass through to the owner’s personal tax return, avoiding corporate-level taxation. To help level the playing field after the corporate tax rate was reduced from 35% to 21% under the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, Congress introduced the Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction. This allows eligible owners of pass-through businesses to deduct up to 20% of their business income. However, the deduction is subject to income limits and restrictions, especially for certain service-based businesses like doctors, lawyers, and consultants.

- Independent Contractor vs. Employee — For years, there has been debate about what makes a worker an independent contractor versus an employee. The IRS uses a three-factor test to determine classification: behavioral control, financial control, and the nature of the relationship. Although the IRS provides this guidance, it can get murky sometimes (e.g. Cambridge advisors). The government tends to prefer employees because taxes are automatically withheld from their paychecks, which basically guarantees that the employee will pay their taxes. Independent contractors, on the other hand, must self-report their income and pay estimated taxes quarterly, which can sometimes lead to underreporting or underpayment of taxes.

- Independent Contractor — An independent contractor typically has more control over how they complete their work, often setting their own hours and working with multiple clients. Examples include freelancers, consultants, and legal or financial advisors. If a business pays a contractor more than $600 in a year, they must report it using Form 1099-NEC.

- Employee — Employees typically work under the control of a single employer, following set hours and receiving instructions on how their job should be performed. Employers must withhold taxes for employees, unlike independent contractors who must handle their own quarterly tax payments.

Ch. 24: Your Investments and Taxes

- Stocks: Long-Term vs. Short-Term Capital Gains — If you sell something like a stock, bond, ETF, or mutual fund for more than you paid for it, you’ve just produced a capital gain, and you’ll have to pay tax on it. Long-term capital gains (produced when selling assets that were held for 12 months or longer) are taxed at a lower rate than short-term capital gains (produced when selling assets that were held for less than 12 months), which are taxed at your ordinary income rate. For example, most people will only owe a 15% tax (20% at the very most) on capital gains from stocks they’ve held for more than a year, rather than paying their ordinary income tax rate (which is usually much higher than 15%) on short-term capital gains. Interestingly, qualified stock dividends are also taxed at the same lower rate.

- Quote (P. 497): “When you buy and hold stocks and stock mutual funds outside retirement accounts, you can take advantage of two major tax breaks. As we discuss in this section, appreciation on investments held more than 12 months and then sold is taxed at the low capital gains tax rate. Stock dividends (not on real estate investment trusts) are also taxed at these same low tax rates.”

- Investing in Stocks Outside of Retirement Accounts — When it comes to investing in stocks, bonds, etc., the biggest tax breaks come from investing within retirement accounts (e.g. company retirement accounts or individual retirement accounts). Why? These accounts offer both tax deductions and tax-deferrals, depending on your income levels and the type of retirement account you’re using. So why would anyone invest in stocks outside of a retirement account? For one, the reduced long-term capital gains tax rates help significantly. Second, some people want the flexibility to be able to do other things with their money, like buy a house. Once your money is placed into a retirement account — at work or in your own individual retirement account — it’s very difficult to get it out without paying hefty penalties and fees. Although retirement accounts offer some nice tax breaks, don’t become obsessed with placing all of your money in them. You need some flexibility to make other moves in your life.

- Quote (P. 498): “If you need to save money outside retirement accounts for short-term purposes such as buying a car or a home, by all means, don’t do all your saving inside sometimes-difficult and costly-to-access retirement accounts. But if you accumulate money outside retirement accounts with no particular purpose in mind (other than that you like seeing the burgeoning balances), why not get some tax breaks by contributing to retirement accounts? Because your investments can produce taxable distributions, investing money outside retirement accounts requires greater thought and consideration, which is another reason to shelter more of your money in retirement accounts.”

- Selling Stocks: Tax Decisions — Inside tax-sheltered retirement accounts, you can buy and sell stocks as much as you’d like. You won’t be taxed on the transactions inside these accounts. When you decide to sell stocks in non-retirement accounts, you have to consider taxes. Below are a few scenarios to think about:

- Selling Gains — If you decide to sell a portion of your shares in a stock that has produced a capital gain, you need to select exactly which shares you want to sell. Say you own 200 shares of Apple and you want to sell 100 of the shares. You bought 100 shares at $50 per share five years ago and the other 100 shares at $100 per share two years ago. Today, the stock is worth $150 per share. Selling the shares you bought at $50 per share will produce a larger capital gain than the capital gain you will produce by selling the shares you bought at $100 per share — meaning you will incur more taxes on the transaction by selling the $50 shares. The smart move is to sell the $100 shares to produce a smaller tax bill on the capital gain. Eventually, you’ll have to pay hefty taxes on those $50 shares when you sell, but it makes good tax sense to prolong the sale for as long as possible. Your brokerage account lets you select shares to sell. If you don’t make a selection, the IRS assumes First In, First Out (FIFO).

- Selling Multiple Stocks — What if you’re considering selling multiple stocks, perhaps to free up some cash to buy a house? You should sell your largest holdings that have the smallest capital gains. This will lead to the lowest possible tax bill. If some of your holdings have capital gains and some have capital losses, sell a little bit of each. By doing so, you can use the capital losses to offset your capital gains — resulting in little to no taxes on the gains.

- Selling Losses — As mentioned in the bullet above, if you have some losers in your portfolio and you’re looking to free up some cash for a house or just want to get rid of them because they have failed you, you can use the losers to offset capital gains from other stocks you sell in the same year. This leads to you paying fewer taxes on the capital gains you sold. If you sell more capital losses than capital gains in a year, those losses can be used to offset up to $3,000 (for single filers) of ordinary income you make from other sources, like your job. If you sell securities with capital losses totaling more than $3,000 in a year, the losses must be carried over to future tax years.

- Tax-Loss Harvesting — Some tax advisors advocate for year-end tax-loss selling, also known as tax-loss harvesting. The idea here is this: Selling stocks that have produced a capital loss and that you no longer believe in will allow you to reduce your taxes when you file in April. As mentioned above, the capital losses can be used to offset any capital gains you made by selling winning stocks during the year, and anything additional can also be used to offset up to $3,000 of ordinary income you produce from your job. In general, you shouldn’t hang on to losing stocks for very long. Rather than hoping the stock rebounds, use your capital losses to lower your taxes and redeploy the money into better investments that will make you money.

Ch. 25: Real Estate and Taxes

- Investing in Real Estate — Tax benefits are one of the big reasons people invest in real estate. Just like investing in retirement accounts yields nice tax breaks, so too does buying and operating real estate. See the chapter 14 and 15 notes for some good information on the many tax breaks available to those who own homes or rent property.

- To Rent or Not to Rent? — The decision to rent, or not rent, a property is a big one that needs to be thoughtfully considered. If you decide to rent a property, you are essentially operating a small business and will need to file Schedule E with your Form 1040. Below are some pros and cons that you should weigh when making the decision:

- Pros:

- Cash Flow — If your rental income exceeds your expenses, you will have “cash flow” hitting your bank account every month. This is especially nice if you own the home outright and do not have a mortgage to pay; you’ll have a good amount of pure cash flow coming to you monthly. With a mortgage, you’ll likely barely break even every month.

- Equity — If you do have a mortgage, the renter’s monthly rental payment is essentially paying the mortgage and helping you build equity in the property. The more equity you have in your property, the wealthier you are.

- Property Appreciation — Home prices typically appreciate steadily over the years and decades. If you hold a property long enough, the price of it should steadily climb over time, allowing you to eventually sell it for a nice gain.

- Tax Advantages — When you operate a rental property, there are many deductions you can claim to offset any of your rental income, allowing you to avoid paying taxes on the rental income. If, after applying deductions, your rental losses exceed your rental income, you can use your rental losses (up to $25,000) to reduce your taxable income from your regular job. See the chapter 15 notes for a full breakdown of the various deductions you can claim. See below for limitations to this.

- Cons:

- Rental Loss Limitations — If your Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) exceeds $150,000, you can’t use rental losses to offset your other income from your regular job. Importantly, this number applies to single filers and married couples filing jointly. The phase out begins at the $100,000 mark. You can still use your rental losses (after claiming all of the great deductions available to you) to offset your rental income, but you can’t use any rental losses to offset income from your regular job.

- Lose the ‘Primary Residence Exclusion’ — The Primary Residence Exclusion allows you to avoid paying capital gains tax on the sale of your house if you’ve lived in the home for two of the last five years and your capital gain was less than $250,000 for single filers and $500,000 for couples. Obviously, if you rent your house and later sell it, you likely lose out on this great exclusion because other people were living in it.

- Stress & Pain — Finding and dealing with tenants, fixing things that break, barely making any cash flow (if you have a mortgage), the stress of two mortgages . . . these are significant downsides to rental property investing that shouldn’t be overlooked. In the end, you will likely do just as well investing in stocks through retirement accounts and non-retirement accounts. You have to decide if the hassle of real estate is worth it. It may be better to have one house and some great-looking retirement and non-retirement accounts.

- Pros:

- Pay Off Your Mortgage Faster? — Most people take out a 30-year mortgage because it allows for the smallest monthly payment possible. But why if you have the funds to pay it off faster? If you’re in this position, you have to decide if the return you can get elsewhere (e.g. via stocks) exceeds the return you get by paying off your mortgage faster. When you pay off your mortgage faster, your return is whatever your interest rate on the mortgage is minus a percentage or two (you have to factor in that mortgage interest is tax deductible). So, if you’re mortgage rate is 5%, paying it off faster probably nets you a return of 4%. Instead of making extra payments toward your mortgage, can those dollars make a better return in something else, like stocks? That’s the decision you have to make. Another big piece of this is whether or not you’ll rent the property eventually. If so, it may make sense to pay it off faster so the monthly payments from your renter are basically pure cash flow. Overall, it depends on your personal preference and whether or not you think you can get a better return from other assets.

Ch. 26: Children and Taxes

- Getting More Financial Aid for College — College costs a lot of money. One of the ways you can try to finance your child’s college education is by applying for financial aid. When it comes to financial aid (scholarships, grants, loans, etc.), the system reviews your income and assets before deciding how much you and your child will receive. The system does not count the money in your retirement accounts, however. This is yet another reason to stash as much money as possible into tax-sheltered retirement accounts. Doing so will put you in position to receive more financial aid. What you shouldn’t do is elect not to contribute to your retirement accounts and instead open a separate non-retirement account to save for your child’s college experience. This money will be counted by the financial aid system when they review your financial life.

- Quote (P. 533): “The financial aid system (to which parents apply so that their children are eligible for college scholarships, grants, and loans) treats assets differently when held outside rather than inside retirement accounts. Under the current financial aid system, the value of your retirement plans is not considered an asset. Thus, the more of your money you stash in retirement accounts, the greater your chances of qualifying for financial aid and the more money you’re generally eligible for.”

- Quote (P. 533): “Therefore, forgoing contributions to your retirement savings plans so you can save money in a taxable account for Junior’s college fund doesn’t make sense. When you do, you pay higher taxes both on your current income and on the interest and growth of this money. In addition to paying higher taxes, money that you save outside retirement accounts, including money in the child’s name, is counted as an asset and leads colleges to charge you higher prices (in other words, reduces your child’s eligibility for ‘financial aid’). Thus, you’re expected to contribute more (pay higher prices) for your child’s educational expenses.”

- Types of Education Plans — Another strategy for funding your child’s college education involves opening up an education account. There are two main types of education investing accounts: Section 529 Plans and the Education Savings Account. More on both of these below:

- Section 529 Plan — These come in two varieties: a prepaid tuition plan and a 529 savings plan. With a prepaid tuition plan, you buy tuition credits at today’s cost and those credits are used when your child attends college in the future. Essentially, you pay for college today. A 529 savings plan works more like a traditional investment account: You put money in the account (contributions are not tax deductible) and it grows over time. The earnings in the account grow tax-free as long as you use the money for qualified educational expenses when your child is in college or grad school. There is no annual contribution limit for a 529 Plan, but contributions are considered gifts for tax purposes. This means that in 2024, you can contribute up to $18,000 per child ($36,000 for married couples) without triggering the federal gift tax. There’s also a special five-year gift tax averaging rule, which allows you to contribute up to $90,000 at once ($180,000 for married couples) and spread it over five years for tax purposes.

- Education Savings Account (ESA) — These are sometimes called ‘Coverdell ESAs’. These allow you to make contributions of up to $2,000 per child per year until the child reaches age 18. The contributions aren’t tax deductible, but ESA investment earnings grow tax-free as long as the funds are used to pay for college costs. These are similar to 529 Plan accounts with one major difference: the contribution limits are much lower. As a result, most people don’t use these and some financial institutions no longer offer them. Also, if you’re a high income earner ($95,000 for single filers and $190,000 for couples), you may not even be able to contribute the full $2,000 per year.

Ch. 27: Estate Planning

- Estate & Inheritance Tax — If you have significant assets that will be passed on to beneficiaries, it makes sense to create an estate. In 2023, upon death, an individual could pass $12.92 million in assets to beneficiaries without paying any federal estate taxes. On the other hand, couples who have their assets, wills, and trusts properly structured could pass $25.84 million to beneficiaries without paying federal estate taxes. Anything above these amounts, you will likely owe federal taxes. What about state estate taxes? Most people have no problem avoiding federal estate taxes, but state estate taxes are more common. Currently, around a dozen states levy estate taxes and six impose inheritance taxes. Type this into Google to get a map of the states who levy estate and/or inheritance taxes.

- What Is a Will? — The main benefit of a will is that it ensures your wishes for the distribution of your assets are fulfilled. If you die without a will (known as intestate), your state decides how to distribute your money and other property. Although your spouse and children will still receive most of your assets, you likely won’t be able to distribute any of it to distant relatives, friends, or charities. A living will (which tells your doctor what, if any, life-support measures you would accept), a medical power of attorney (which grants someone you trust the ability to make medical decisions for you if you are unable), and a durable power of attorney are usually also established in a standard will.

- Reducing Estate Taxes: Gifting — What are some ways you can reduce possible estate taxes? One way is by gifting your money to people. In 2023, people were allowed to give up to $17,000 per year to as many people — such as children, grandchildren, or friends — as desired without any gift tax consequences or tax forms required. The benefit of giving is that it removes the money from your estate and therefore reduces your taxes. You can use gifting to remove a substantial portion of your assets from your estate over time. The problem is that you really don’t know when you’ll die.

- Gifting: Think Strategically — In terms of what you can give as gifts, you can give money, stocks, bonds, etc. The key is to be strategic about it. Start with cash and assets that haven’t increased in value since you bought them. If you want to gift an asset that has lost value, you should sell it first because it will allow you to take a tax deduction. Then you can give the money after you’ve sold. What about assets that have appreciated in value a lot? Rather than gifting them, consider holding these until your death. Doing so will allow your heirs to inherit the asset at its “stepped-up” cost basis, which means their cost basis becomes whatever the market value of the asset is at the time they inherit it, rather than assuming the cost basis that the asset was originally purchased at. This essentially wipes out the capital gains tax that would have been owed if you had sold the asset. This is important because if you gift appreciated assets, the recipient receives the original cost basis, which will lead to a lot of capital gains tax. Another option you have is to gift the appreciated assets to charity. This allows you to claim a tax deduction for giving to charity and you don’t have to pay any capital gains.

- Quote (P. 548): “You have options in terms of what money or assets you give to others. Start with cash or assets that haven’t appreciated since you purchased them. If you want to transfer an asset that has lost value, consider selling it first; then you can claim the tax loss on your tax return and transfer the cash. Rather than giving away assets that have appreciated greatly in value, consider holding onto them. If you hold such assets until your death, your heirs receive what is called a stepped-up basis. That is, the IRS assumes that the effective price your heirs ‘paid’ for an asset is the value on your date of death — which wipes out the capital gains tax that otherwise is owed when selling an asset that has appreciated in value. (Donating appreciated assets to your favorite charity can make sense because you get the tax deduction for the appreciated value and avoid realizing the taxable capital gain.)”