Short Summary

One hundred thousand years ago, there were at least six species of humans. What happened to the others? How did we emerge from an ordinary animal in the animal kingdom to the planet’s undisputed dominant species? What are the factors driving our incredible growth over the last 500 years? In Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari dives into the complicated and fascinating history of human beings.

Key Takeaways

Favorite Quote

“Nobody, least of all humans themselves, had any inkling that their descendants would one day walk on the moon, split the atom, fathom the genetic code, and write history books. The most important thing to know about prehistoric humans is that they were insignificant animals with no more impact on their environment than gorillas, fireflies, or jellyfish.”

Book Notes

Ch. 1: An Animal of No Significance

- About the Book — Sapiens is one of the most successful books of all time. It has been translated into more than 50 languages and sold over 10 million copies worldwide. The book covers the history of human life, beginning with our first days on Earth 2.5 million years ago.

- About the Author — Yuval Noah Harari has a PhD in history from the University of Oxford. He lectures at the department of history at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, specializing in world history.

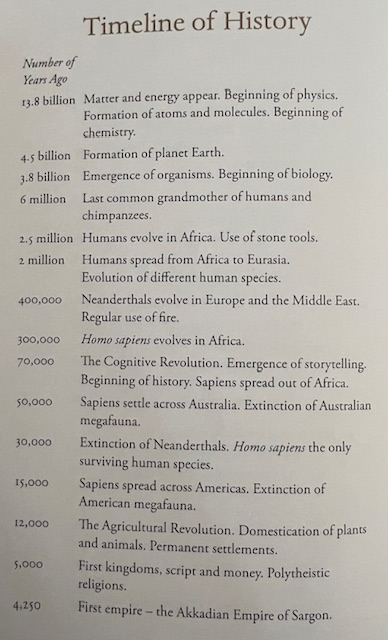

- Brief Timeline of Events — To help set the stage for this book, it’s important to have a grasp on how and when our universe and planet developed. Below is a short timeline. See the bottom of these notes for a longer timeline.

- 14 Billion Years Ago — The Big Bang happened. Energy, time, and space came into being.

- 4 Billion Years Ago — The first organisms on Earth appear

- 2.5 Million Years Ago — The very first human species (Homo Habilis) appears in East Africa

- 150,000 Years Ago — Modern humans (Homo Sapiens) appear

- Prehistoric Humans — The very first human-like beings (Homo Habilis) first appeared in East Africa some 2.5 million years ago. They were truly nothing special. There was nothing to indicate that these early humans would develop into what we see today.

- Quote (P. 4): “Nobody, least of all humans themselves, had any inkling that their descendants would one day walk on the moon, split the atom, fathom the genetic code, and write history books. The most important thing to know about prehistoric humans is that they were insignificant animals with no more impact on their environment than gorillas, fireflies, or jellyfish.”

- Homo Sapiens — Homo, meaning man or human being, is the genus we belong to. A ‘genus’ is a species that evolved from one common ancestor. Sapien, meaning wise, is the actual species that we are. Homo Sapiens. Wise Man. This is what all of us today are classified as. We evolved from great apes, and our nearest living relatives are chimps, gorillas, and orangutans. Every single one of us has a single ancestral ‘grandmother’ who gave rise to all of us. This grandmother was a female ape.

- Quote (P. 5): “Like it or not, we are members of a large and particularly noisy family called the great apes. Our nearest living relatives include chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans. The chimpanzees are the closest. Just 6 million years ago, a single female ape had two daughters. One became the ancestor of all chimpanzees, the other is our own grandmother.”

- Multiple Human Species — Today, every human is a Homo Sapien. But from 2 million years ago to about 10,000 years ago, at least six different species of human beings appeared on the planet. Just like there are multiple species of bears (e.g. polar bear, black bear, brown bear, grizzly bear), there were multiple species of humans. This is contrary to what most people believe. Many people are under the impression that only one species of human was around at any point in time. In reality, there were several species of human beings around simultaneously. Some of these include:

- Homo Neanderthalenis (“Neanderthals”)

- Homo Erectus

- Interestingly, Homo Erectus is the most durable human species in history, having lived for more than 2 million years. For context, Homo Sapiens have been around for only 100 or 150,000 years.

- Homo Soleonsis

- Homo Floresiensis

- Homo Sapiens

- Homo Habilis

- Homo Denisova

- Homo Ergaster

- Quote (P. 8): “The members of some of these species [Homo] were massive and others were dwarves. Some were fearsome hunters and others meek plant-gatherers. Some lived only on a single island, while many roamed over continents. But all of them belonged to the genus Homo. They were all human beings.”

- Quote (P. 8): “The truth is that from about 2 million years ago until around 10,000 years ago, the world was home, at one and the same time, to several human species.”

- Uniquely Human Traits — There are a few traits that set us apart from any other animal form and helped us become the world’s dominant species. These include:

- Jumbo Brain — Compared to every other living thing, we have a massive brain. The brain of a modern human accounts for only 2-3% of total body weight, but it consumes 25% of the body’s energy. The brain is a very energy-greedy organ. It demands a lot of fuel.

- Upright — We can walk on two legs. We evolved this ability to be able to spot predators on the open savannah. This allowed us to use our arms and hands for other purposes. Over time, our palms and fingertips evolved to become very good at movements that involve a lot of precision and dexterity, including using weapons and tools.

- Fire — By about 300,000 years ago, Homo Eructus, Neanderthals, and the forefathers of Homo Sapiens were experts at creating fire. This helped keep humans warm, gave them a weapon against predators, and allowed them to cook food, which killed off bad bacteria and allowed for the consumption of things like rice, wheat, potatoes, and more.

- Early Humans: Middle of the Pack — Again, early humans really were not that impressive. On the food chain, we were somewhere in the middle. In fact, scientists have found that we ate a lot of bone marrow. This is because it was one of the only things we could eat other than plants, insects, and other small things. We would wait for a lion to eat something, wait for hyenas to clean up the dead body, then we would swoop in and eat whatever was left. About 400,000 years ago is when we finally started hunting big game. And 100,000 years ago is when our tools and weapons allowed us to go to the top of the food chain. Today, we’re firmly on top.

- Homo Sapiens: Venturing Out — Homo Sapiens that looked just like us first appeared in East Africa 150,000 years ago. This was our place of origin. From there, about 70,000 years ago, we ventured out into the Middle East before pushing into Asia and Europe, later somehow crossing the ocean to reach Australia. Then we pushed into North America and South America until we had conquered the globe. Along the way, we encountered other species of human like the Neanderthals and Homo Erectus. For various reasons, some of which are still unclear, we emerged as the top human species. Today, all of us are Homo Sapiens.

- Where Did the Other Humans Go? — Before Homo Sapiens appeared in East Africa and began venturing out, there were multiple species of humans living in nearby areas. It didn’t take long before we were the only human species left. So what happened to the others? There are several theories about this. Did we simply out-compete Neanderthals and other human species by being better at gathering food and other resources? Or did we violently execute the other species? The answer is unclear. What is clear is that human species that had lived for several hundreds of thousands of years, like the Neanderthals (400,000 years), quickly went extinct after Homo Sapiens arrived on the scene. We wiped them out. The question is how?

- Chapter Takeaway — Up until about 10,000 years ago, there were several different species of humans. Homo Sapiens is now the only species left. There are several theories about why that is. Did we simply out-compete the others to the point of extinction, or did something more sinister happen?

Ch. 2: The Tree of Knowledge

- The Cognitive Revolution — The Cognitive Revolution is used to describe the remarkable developments in Homo Sapiens that occurred between 70,000 and 30,000 years ago. In short, we became drastically more intelligent and skilled, and we started communicating with each other at a much higher level. These developments are primarily what allowed us to conquer the world over other human species and animals. Prior to this period, we really weren’t that impressive and didn’t stand out from other animals. What caused us to become so much more sophisticated? Nobody knows. But most believe it has something to do with the wiring in our brains.

- The Cognitive Revolution: Why We Became Top Dog — We were able to conquer the world during the Cognitive Revolution primarily because our systems of communication improved drastically at this time. Every animal knows how to communicate. Chimps, elephants, whales, and dolphins are some of the best at it. But Homo Sapiens began to communicate with each other much more efficiently. Below are a few features that gave us an advantage over other animals:

- Lots of Information — Our language is very flexible. About 70,000 years ago, we acquired the ability to connect a limited number of sounds and signs to communicate an infinite amount of meaning and information. Other animals can’t do this. A chimp can make a sound that warns others in its pack that a lion is nearby. But the chimp can’t tell the others exactly where the lion is located or what it looks like. Humans can. We not only can give every possible detail about the lion, but we can also work together to devise a strategy for escaping it or hunting it. This gave us a massive advantage over other animals.

- Quote (P. 25): “Sapiens can cooperate in extremely flexible ways with countless numbers of strangers. That’s why Sapiens rule the world, whereas ants eat our leftovers and chimps are locked up in zoos and research laboratories.”

- Gossip & Social Relationships — The amount of information our linguistic skills allow us to pass on to each other enables us to talk about social relationships (i.e. gossip). This is crucial for being able to pass on reliable information about who can be trusted. This allowed us to build larger and larger groups, or tribes. Larger groups allowed us to become more coordinated in our team efforts, dominate other animals, and achieve more overall success. Other animals can’t communicate about social relationships as well as we can.

- Stories & Myths — Humans love stories. And the linguistic skills we gained 70,000 years ago opened up all kinds of possibilities regarding stories. Nations, companies, money, laws — these are all examples of stories we tell each other to gain cooperation. An American will go to battle for another American because both parties believe in the United States. In reality, these things are products of the human imagination. Other animals don’t believe in anything but reality. You can’t convince a chimp to hand over his banana because he’s going to get an unlimited supply in monkey heaven. By being able to tell stories, humans were able to build massive cities, empires, nations, teams, and companies that rally around a central belief. Other animals simply aren’t able to manufacture this kind of large-scale cooperation.

- Quote (P. 27): “How did Homo Sapiens manage to cross this critical threshold, eventually founding cities comprising tens of thousands of inhabitants and empires ruling hundreds of millions? The secret was probably the appearance of fiction. Large numbers of strangers can cooperate successfully by believing in common myths. Any large-scale human cooperation — whether a modern state, a medieval church, an ancient city, or an archaic tribe — is rooted in common myths that exist only in peoples collective imagination.”

- Lots of Information — Our language is very flexible. About 70,000 years ago, we acquired the ability to connect a limited number of sounds and signs to communicate an infinite amount of meaning and information. Other animals can’t do this. A chimp can make a sound that warns others in its pack that a lion is nearby. But the chimp can’t tell the others exactly where the lion is located or what it looks like. Humans can. We not only can give every possible detail about the lion, but we can also work together to devise a strategy for escaping it or hunting it. This gave us a massive advantage over other animals.

- The Cognitive Revolution: Stories & Myths — The bullet above about our ability to invent stories and myths is so important that I’m adding more here. This was one of the primary reasons we conquered other human species and animals during the Cognitive Revolution about 70,000 years ago. Our ability to tell stories and create myths enables millions of strangers to cooperate and work toward common goals. It also enables us to quickly change behavior. Prior to the Cognitive Revolution, which is when Homo Sapiens became much more skilled and better at communication, all human species advanced at the rate that their genes evolved and advanced. Our newfound ability to communicate led to the creation of stories and myths that drove significant change, much faster. As an example, Homo Erectus built the same exact tools for 2 million years. In the last 30,000 years alone, Homo Sapiens have advanced from sticks with flint spearheads to nuclear weapons. This type of rapid advancement requires the ability to work together with thousands and millions of strangers. No other animal group can do this.

- Quote (P. 34): “In other words, while the behavior patterns of archaic humans remained fixed for tens of thousands of years, Sapiens could transform their social structures, the nature of their interpersonal relations, their economic activities and a host of other behaviors within a decade or two.”

- Quote (P. 34): “This was the key to Sapiens’ success. In a one-on-one brawl, a Neanderthal would probably have beaten a Sapiens. But in a conflict of hundreds, Neanderthals wouldn’t stand a chance. Neanderthals could share information about the whereabouts of lions, but they probably could not tell — and revise — stories about tribal spirits. Without an ability to compose fiction, Neanderthals were unable to cooperate effectively in large numbers, nor could they adapt their social behavior to rapidly changing challenges.”

- Chapter Takeaway — The Cognitive Revolution occurred about 70,000 years ago. During this period, Homo Sapiens suddenly became much more skilled and better at communication. The communication piece is what allowed us to conquer other human species and animals. We were suddenly able to easily pass along a lot of information to friends and strangers. This ability to work toward goals alongside thousands and millions of other people, paired with an ability to manufacture stories and myths that united large groups, gave us a huge advantage and enabled us to create nations, empires, corporations, teams, and more.

Ch. 3: A Day in the Life of Adam and Eve

- Day in the Life of an Ancestor — By and large, it’s difficult to fully understand at a granular level what life was like for ancient Homo Sapiens who lived during the Cognitive Revolution of 30-70,000 years ago. Most historians and researchers agree that there was no “one way” of life. Rather, we were bunched into many small groups and tribes that had their own language, habits, migration patterns, eating schedules, and more. A member of one Homo Sapien group had a much different life than a member of another group. That said, below are a few characteristics of Homo Sapien life back then that are widely accepted:

- Small Groups — As mentioned, we lived in very small groups. These groups ranged in size from as few as a dozen to as many as 100. These groups had their own way of doing things. They would hunt, fight, and feast together.

- “On the Road” — We spent most of our time roaming around in search of food and supplies. We tended not to stay in the same place for long. Our movement was influenced by changing seasons, migration patterns of animals, and the growth cycle of plants.

- Exploration — Although most of our movement was restricted to places we knew a lot about, we also explored new areas occasionally. These wanderings into new areas are what allowed us to expand and become a worldwide animal.

- Permanent Residences — Most Homo Sapiens moved around every day, week, and month. But some of us set up permanent residences along seas and rivers rich in seafood. These were fishing villages.

- Hunting and Gathering — We hunted for food, but most of our time was wasted spent gathering things such as flint, wood, and bamboo. We picked berries, scrounged for termites, dug for roots, stalked rabbits, and hunted bison and mammoth.

- Smart Cookies — Looking at the individual level, ancient Homo Sapiens might be the smartest people to ever live. They had to be. They couldn’t survive without knowing weather patterns, signs of danger, plant cycles, how to turn a flint stone into a spear point, and so much more.

- Many Mates — Some groups advocated for a man having multiple and many different partners. Other groups preferred monogamous relationships. It sort of depended on the group. Some researchers argue that the reason there is a lot of infidelity today has to do with the fact that many of our ancestors had relationships with many women. The theory is that our tendency to have a wandering eye might be hard-wired in.

- Varied Diet — One of the secrets to our ancestors’ success was their varied diet. It kept them free of malnutrition and starvation. They ate all kinds of things: berries, fruit, snails, turtle, rabbit steak, onion, and so much more. The variety of their diet ensured that they received all of the nutrients they needed.

- Why We Binge Eat — The reason many of us binge eat and have a hard time not throwing down sweets like ice cream and other high-calorie foods goes back to the eating habits of ancient Homo Sapiens. In the forests and savannahs we inhabited, high-calorie sweets were rare and food in general was hard to come by. Ripe fruit was about the only sweet treat available to a human 30,000 years ago. If a man in the Stone Age came across a tree filled with ripe fruit, he immediately ate as much as he could before some other animal in the area could do it first. This instinct to gorge on high calorie food was basically hard-wired into our genes. This is called the ‘gorging gene theory’, and it is widely accepted.

- Dogs: Man’s Best Friend for 15,000 Years — The dog was the first animal domesticated by Homo Sapiens. Dogs traveled with us, fought with us, alerted us to danger (i.e. bark), and kept us company. Evidence points to dogs joining our groups at least 15,000 years ago. This is likely one of the many reasons modern humans have such deep connections with dogs; they’ve been by our side for 15,000 years. We don’t have anywhere near as strong of a bond with any other animal.

- Quote (P. 46): “A 15,000-year bond has yielded a much deeper understanding and affection between humans and dogs than between humans and any other animal. In some cases dead dogs were even buried ceremoniously, much like humans.”

- The Curtain of Silence — There’s a lot about ancient Homo Sapiens that we simply do not know. Were they highly political? If so, what kind of political systems were in place? They appear to have been religious, but who, or what, did they worship; was it a universal god, or was it a big rock located nearby? It appears war and violence did occur at times between groups, but how prevalent were these acts? In some of these areas, there just isn’t enough evidence to confidently say what humans from 30-70,000 years ago believed or thought. It’s subjective.

- Chapter Takeaway — Sapiens of 30-70,000 years ago spent much of their time hunting and gathering, roaming around, and exploring new territories. They lived a simple life. They stuck together in small groups. Beyond that, it’s very difficult to know what they believed or thought.

Ch. 4: The Flood

- Traveling to Australia — The first Sapiens appeared in East Africa about 150,000 years ago and slowly began venturing out to nearby areas in Africa and Asia. The ocean prevented Sapiens from pushing beyond the Afro-Asian area. But that all changed during the Cognitive Revolution of 30-70,000 years ago. During this period, we developed the technology and organizational skill to break into the Outer World. Our first huge achievement came 45,000 years ago, when Sapiens somehow traversed the open ocean to reach Australia. This feat was miraculous. It was mission impossible. It required the ability to build sturdy boats that could withstand the violent ocean. But more impressively — these Sapiens had no idea where they were going. They had no idea what was out there. There were no maps at the time, and no human had ever set foot on Australia.

- Quote (P. 63): “Their [Sapiens’] first achievement was the colonization of Australia some 45,000 years ago. Experts are hard-pressed to explain this feat. In order to reach Australia, humans had to cross a number of sea channels, some more than 60 miles wide, and upon arrival they had to adapt nearly overnight to a completely new ecosystem.”

- Quote (P. 64): “The journey of the first humans to Australia is one of the most important events in history, at least as important as Columbus’s journey to America or the Apollo II expedition to the moon.”

- Conquering Australia — Arriving in Australia was a significant moment in early human history. We later used our boats to conquer nearby islands to the north of Australia. What we encountered in Australia was unlike anything we had seen before in Africa and Asia. The ecosystem was completely different. There were 6-foot-tall, 450-pound kangaroos, as well as enormous Koalas, lions, snakes, and lizards. Within a few thousand years, almost all of these giants vanished. Of the 24 species in Australia weighing more than 100 pounds or more, 23 became extinct. We were largely responsible for that. We became the deadliest animal on the planet.

- Quote (P. 64): “The moment the first hunter-gatherer set foot on an Australian beach was the moment that Homo Sapiens climbed to the top rung in the food chain, and became the deadliest species ever in the four-billion-year history of life on Earth.”

- Quote (P. 65): “The settlers of Australia, or more accurately, its conquerors, didn’t just adapt. They transformed the Australian ecosystem beyond recognition.”

- Pushing Into North America — Sapiens eventually pushed into the western hemisphere, arriving in North America about 16,000 years ago. They were able to arrive by foot because sea levels were so low at the time that there was a land bridge connecting Siberia to Alaska. The trip from Siberia to Alaska certainly wasn’t easy. It was extremely cold, and Sapiens had to learn to make warm clothes and develop new hunting techniques and weapons in order to track and kill mammoths and other big game of the far north. Their route from Alaska into the rest of Northern America was initially blocked by glaciers, but global warming melted them about 14,000 years and allowed passage into the rest of the continent. Sapiens then pushed into a variety of places in North America, including Canada and the western U.S. They also pushed into South America.

- Quote (P. 70): “Descendants of the Siberians settled the thick forests of the eastern United States, the swamps of the Mississippi Delta, the deserts of Mexico, and steaming jungles of Central America. Some made their homes in the river world of the Amazon basin, others struck roots in Andean mountain valleys or the open pampas of Argentina. And all this happened in a mere millennium or two! [one or two thousand years]”

- Human Terror — No matter where we go, we wreak absolute havoc on the existing animal population. We have single-handily erased countless animal species during our conquering of the world. Australia, New Zealand, Alaska, the Americas, Madagascar, Hawaii — the list goes on. Everywhere we go, we kill off the majority of animals that had called the area home. Our ancestors hunted giant animals in Australia and used fire to burn many of the forests in the area to the ground. In addition to hunting the animals, taking down the forests had a major negative impact on Australia’s ecosystem; the local animals couldn’t adapt to new food chains. Sapiens first reached New Zealand 800 years ago. Within a few centuries, most of the big animals and 60% of bird species were extinct. About 4,000 years ago, the mammoths of the Arctic island Wrangel suddenly disappeared not long after Sapiens first reached the island. This trend of making animals disappear continued when we flooded into North and South America.

- Quote (P. 71): “The Americas were a great laboratory of evolutionary experimentation, a place where animals and plants unknown in Africa and Asia had evolved and thrived. But no longer. Within 2,000 years of the Sapiens arrival, most of these unique species were gone. According to current estimates, within that short interval, North America lost thirty-four out of its forty-seven genera of large mammals. South America lost fifty out of sixty. The sabre-tooth cats, after flourishing for more than 30 million years, disappeared, and so did the giant ground sloths, the oversized lions, native American horses, native American camels, the giant rodents, and the mammoths. Thousands of species of smaller mammals, reptiles, birds, and even insects and parasites also became extinct.”

- Quote (P. 74): “Don’t believe tree-huggers who claim that our ancestors lived in harmony with nature. Long before the Industrial Revolution, Homo Sapiens held the record among all organisms for driving the most plant and animal species to their extinctions. We have the dubious distinction of being the deadliest species in the annals of biology.”

- Chapter Takeaway — Sapiens crossed the ocean into Australia about 45,000 years ago and pushed into North America 16,000 years ago. No matter where we have gone, we have caused major destruction to existing ecosystems. We are responsible for countless animal extinctions and have become the deadliest creatures on the planet.

Ch. 5: History's Biggest Fraud

- The Agricultural Revolution — For 2.5 million years, human species relied on hunting and gathering for food and resources. All of this changed 10,000 years ago with what scholars call the Agricultural Revolution. Around this period, Sapiens began to devote most of their time to growing plants, sowing seeds, and raising animals to produce food. In other words, they became farmers. This gradual change of behavior was in an effort to produce our own fruit, grains, and meat. Wheat, rice, corn, potatoes, and barley — these were a few of the plants our ancestors spent most of their time planting and growing during the Agricultural Revolution. Even today, most of our calories still come from these plants.

- Quote (P. 78): “Even today, with all our advanced technologies, more than 90% of the calories that feed humanity come from the handful of plants that our ancestors domesticated between 9500 and 3500 BC — wheat, rice, maize (called ‘corn’ in the US), potatoes, millet and barley.”

- The Agricultural Revolution: Pros & Cons — The transition to farming and agriculture happened gradually over thousands of years. We slowly became better and better at farming and growing wheat until it became a permanent occupation for most of our ancestors. The hunting and gathering lifestyle came to an end for most; there wasn’t any time left for it. But the Agricultural Revolution actually lowered the overall quality of life for Sapiens. The author argues that it was not an improvement to the hunter-gatherer approach. Below are a few of the pros and cons of this new way of life.

- Con: Poor Diet — Diets became less healthy during the Agricultural Revolution. Humans are omnivorous apes who enjoy a wide variety of food. The Agricultural Revolution led to a diet full of grains and wheat. These foods are not easy to digest and are generally not as healthy.

- Con: Dependence on Crops — Sapiens who decided to settle down and raise crops and wheat fields became extremely dependent on these food products. If extreme weather or some kind of fungus killed the crops, these Sapiens were in trouble. They put all of their eggs in one basket. If drought or famine hit, thousands of people died of starvation.

- Con: Labor — It takes an enormous amount of effort and time to raise crops. It requires clearing fields, putting up fences, chasing away animals, and more. This work put a lot of stress on the back and body.

- Con: Violence — A lot of violence broke out around agricultural fields. Because Sapiens settled down to raise crops, they were more likely to stay around and fight any group who approached their village. Sapiens who were hunter-gatherers didn’t really have a home; they were always wandering. It was therefore easier to avoid violence.

- Con: Disease — Setting up permanent villages meant the end of roaming around from place to place. But this came with consequences for early farmers. Permanent settlements were hotbeds for infectious diseases. These diseases wiped out a lot of people.

- Pro: Population Growth — If there were so many cons of the Agricultural Revolution, why would Sapiens choose to become farmers? Really the only advantage offered by this new way of life was that it produced more food, which helped keep people alive and allowed them to reproduce at a greater rate. The time and attention needed to grow crops also led to the construction of villages and permanent residences. The population of Sapiens exploded during the Agricultural Revolution.

- Quote (P. 98): “The Agricultural Revolution is one of the most controversial events in history. Some partisans proclaim that it set humankind on the road to prosperity and progress. Others insist that it led to perdition. This was the turning point, they say, where Sapiens cast off its intimate symbiosis with nature and sprinted towards greed and alienation. Whichever direction the road led, there was no going back. Farming enabled populations to increase so radically and rapidly that no complex agricultural society could ever again sustain itself if it returned to hunting and gathering.”

- Sad Life of Farm Animals — In addition to growing wheat, potatoes, corn, rice, and other crops, Sapiens in the Agricultural Revolution began to domesticate animals like pigs, chickens, sheep, and cows. This was the start of a terrible future for these animals. They were, and still are, treated horribly. We raise them in order to get milk, meat, and eggs, then slaughter them. While they’re alive, they live in terrible conditions. They’re trapped in pens and cages; they are often abused by their owners in order to produce obedience; and they are never allowed any freedom. Sadly, these are some of the most miserable animals on the planet.

- Chapter Takeaway — The Agricultural Revolution emerged about 10,000 years ago and effectively put an end to the hunter-gatherer lifestyle used by human species for more than 2 million years. Although the Agricultural Revolution was initiated to produce more food and grow the population of Sapiens, it led to many unforeseen consequences. The author makes the argument that the Agricultural Revolution made us worse off, which I disagree with.

Ch. 6: Building Pyramids

- Building Nations — The Agricultural Revolution ushered in a new lifestyle for Sapiens. Rather than roaming around hunting and gathering, more and more humans began settling down into permanent residences to farm. This eventually led to villages. Then towns. Then cities. Then nations. Around 4,000 years ago, Sargon the Great formed the first empire, the Akkadian. The empire boasted more than a million people. Around 3,000 years ago, the first mega-empires appeared in the Middle East: The Assyrian Empire, the Babylonian Empire, and the Persian Empire. These empires had several million people. The Roman Empire and Qin Dynasty (China) appeared about 2,100 years ago.

- The “Imagined Order” — While discussing the arrival of early empires, cities, and kingdoms, the author returned to a point from a previous chapter about shared myths. His point is that it isn’t possible to gain the cooperation of hundreds, thousands, and millions of people without using stories and shared myths. Examples of shared myths include ideas like money, human rights, liberty, laws, companies, and actual nations (e.g. the United States). He calls these shared myths the “imagined order.” These myths serve an important purpose: they regulate behavior and get people to cooperate with each other. They keep people in line. Without the imagined order, the author says, there would be complete chaos. An example of an imagined order, per the author, is the Declaration of Independence.

- Chapter Takeaway — The “imagined order” is what unites people and led to the creation of villages, towns, cities, and nations. Without these shared myths (e.g. the Declaration of Independence), humans would not be able to work together and society would not function in an organized fashion like it does today.

Ch. 7: Memory Overload

- Introducing Writing — After the Agricultural Revolution, we ran into a problem. We were at a point where villages of hundreds of people were commonplace. The sheer amount of transactions and interactions going on between people had reached a point where we needed some kind of permanent record to store data. There was too much information for our brains to remember. This led to the invention of writing. The ancient Sumerians of Mesopotamia invented the first system of writing 5,500 years ago. The invention of writing allowed us to keep a permanent record of data, leading to the creation of towns, cities, and kingdoms comprised of thousands and millions of people.

- Storing Data — Writing was invented to help us preserve data and keep a permanent record of transactions. As a result, all of the first texts of history are simply a bunch of mathematical economic documents that recorded the payment of taxes, various debts, and the ownership of property. It wasn’t until later on that we began to use writing to express thoughts through poetry, letters, books, cookbooks, and more. An example of one of the first full scripts is the hieroglyphics created by the Egyptians roughly 4,500 years ago. We later developed techniques for cataloging and storing in an efficient manner all of the written information people were creating.

- Chapter Takeaway — Humans invented writing about 5,500 years ago in order to better record transactions and interactions among people. This led to huge growth. We went from small villages of several hundred people to cities, kingdoms, and empires of thousands and millions of people. Writing was initially developed to help us preserve data, but we later expanded our use of it to share thoughts through books, letters, and more. This played a key role in shaping human culture and intellectual history.

Ch. 8: There Is No Justice in History

- The Myth of Hierarchies — Building on the point about myths and the “imagined order” from previous chapters, the author’s big point in this chapter is that hierarchies and categories like superiors, commoners, and slaves; whites and blacks; men and women; and rich and poor people are simply myths that we have created in our mind. These myths have permeated society and have led to perceived hierarchies where certain people are legally, politically, or socially superior to others. In reality, we are all equal. We share 99.9% of the same genes. There are no biological differences that make a black person inferior to a white person, for example. Or a woman inferior to a man. Any perceived differences between these groups are the result of our imagination, and the beliefs have spread across our culture.

- Quote (P. 144): “Most sociopolitical hierarchies lack a logical or biological basis – they are nothing but the perpetuation of chance events supported by myths.”

- Men vs. Women — An example of the point above is men vs. women. The only difference between men and women from a biological standpoint involves chromosomes. Males have XY chromosomes; females have an XX. All other perceived differences that make men seem superior to women in society are myths that are products of our imagination. They aren’t real. For example, from the second they are born, men in our society are assigned masculine roles like engaging in politics and business, voting, and military service. Women are assigned feminine roles like raising children, cooking in the kitchen, and being obedient to the husband. These beliefs are products of our imagination, and they have changed throughout history (e.g. women used to not be able to vote; now they can). In reality, women are just as capable as men in most areas.

- Quote (P. 148): “Most of the laws, norms, rights and obligations that define manhood and womanhood reflect human imagination more than biological reality.”

- Quote (P. 152): “Sex is divided between males and females, and the qualities of this division are objective and have remained constant throughout history. Gender is divided between men and women (and some cultures recognize other categories). So-called ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ qualities are inter-subjective and undergo constant changes.”

- Chapter Takeaway — Certain biases in our society are the products of the human imagination. They aren’t real. Race, gender, and sexual orientation are examples. In reality, there is nothing “unnatural” about people who fall on either side of the fence in these areas. But there is no doubt that, collectively, we have over the course of history viewed certain people as inferior (e.g. racism: blacks are inferior to whites). These prejudices are complete myths. Biologically, we are all 99.9% the same.

Ch. 9: The Arrow of History

- Worlds Apart — For most of our history, humans lived in their own “worlds.” These “worlds” were located in different parts of Earth and operated as their own civilizations. They ate their own unique types of food, participated in their own hobbies, had their own culture, and made up their own rules. In fact, most humans had no idea that there was anybody else out there. There used to be hundreds and thousands of “worlds,” but by the year 1450, it was down to five worlds.

- Afro-Asia World — 90% of humans lived in this world. This area included Asia, Europe, and most of Africa.

- The Mesoamerican World — This area encompassed most of Central America and parts of North America

- The Andean World — Encompassed most of western South America

- The Australian World — Encompassed the entire continent of Australia

- The Oceanic World — Encompassed most of the islands of the south-western Pacific Ocean, from Hawaii to New Zealand

- One World — Over the next 300 years, the Afro-Asia world conquered and consumed the other four worlds. Everybody was now part of the same world. There were still differences among people, but everybody knew about everybody else. There were no longer any groups out there doing their own thing. There were a couple of factors that helped create a unified world. They are listed below and are discussed at length in the next three chapters.

- Money

- Empires

- Religion

- Quote (P. 237): “Commerce [money], empires and universal religions eventually brought virtually every Sapiens on every continent into the global world we live in today.”

- Chapter Takeaway — It wasn’t until fairly recently that we became one world. Going back to the days of the hunter gatherers, there were hundreds and thousands of groups. As time went on, the number of groups living in their own world dwindled until we became one unified world.

Ch. 10: The Scent of Money

- Money: The First Unifying Force — The creation of money helped fuel the growth of empires and large cities. Before money, people would trade favors. If somebody gave somebody else an item or provided assistance with something, they would expect a favor in return at a later date. This was not sustainable in large groups. There needed to be some sort of currency that could be exchanged and traded among strangers for any kind of item. This need led to the invention of money. Money itself does not have a lot of value. It is built on a shared belief and is completely worthless if nobody believes in it. Money was one of the factors that enabled us to build huge empires and cities.

- Quote (P. 179): “Because money can convert, store, and transport wealth easily and cheaply, it made a vital contribution to the appearance of complex commercial networks and dynamic markets. Without money, commercial networks and markets would have been doomed to remain very limited in their size, complexity, and dynamism.”

- Quote (P. 180): “People are willing to do such things when they trust the figments of their collective imagination. Trust is the raw material from which all types of money are minted.”

- Quote (P. 180): “Money is accordingly a system of mutual trust, and not just any system of mutual trust: money is the most universal and most efficient system of mutual trust ever devised.”

- Types of Money — Over the centuries, all kinds of items have been used as money. Before coins and paper currency, people used shells, cattle, skins, salt, grains, beads, and cloth as currency. The first coins in history were minted 2,700 years ago by King Alyattes of Lydia. These coins were made of gold or silver and featured an imprint to guarantee their value. Modern money also has these imprints. The acceptance of gold and silver coins across different cultures helped pave the way for extensive trade networks. Again, it’s not the physical item itself that holds value, but the shared belief in what money represents.

- Interesting Fact — Today, the sum of all money in the world is $60 trillion, yet the sum of all coins and banknotes is $6 trillion. More than 90% of all money exists only on computer servers. But as long as people believe in it, money has value.

- Chapter Takeaway — The invention of money paved the way for extensive trade networks and allowed humans to create bigger and bigger groups. Physical money itself (e.g. coins or printed money) has very little value; it’s the collective shared belief in money that gives it value.

Ch. 11: Imperial Visions

- Empires: The Second Unifying Force — In this chapter, the author explores the rise and impact of empires throughout history. Money (previous chapter), empires (this chapter), and religion (next chapter) are the three factors that helped bring the world into one unit. He argues that empires, despite using extreme violence to expand, have played a crucial role in uniting diverse peoples under common political and cultural systems. He explains how empires spread ideas, technologies, and religions, contributing to the development of global culture. He also discusses how imperialism, while oppressive, has shaped the modern world by creating complex networks of trade, government, and communication. He ultimately suggests that the legacy of empires is both positive and negative, leaving a lasting influence on human history.

- Chapter Takeaway — Empires were the second unifying force that helped bring the world together. Empires brought millions and millions of people together under common cultural and political views.

Ch. 12: The Law of Religion

- Religion: The Third Unifying Force — Religion is the third and final force that unified humankind. Although humans have always believed in certain things, actual organized religions didn’t appear until about 3,000 years ago (1,000 BC). Religions are defined as systems of human norms and values that are founded on belief in a superhuman order. They made a major impact by aligning people under certain belief systems.

- Quote (P. 211): “As far as we know, universal and missionary religions began to appear only in the first millennium BC. Their emergence was one of the most important revolutions in history, and made a vital contribution to the unification of humankind, much like the emergence of universal empires and universal money.”

- Types of Religions — Over the course of history, many kinds of religions have existed. These religions have served the purpose of unifying followers under a specific code of conduct and belief system. They brought meaning to the world for many people.

- Polytheism — Polytheism was the first major type of religion to emerge. It is the belief in several gods (i.e. the Greek gods). These religions understood the world to be controlled by a group of powerful gods, such as the fertility goddess, the rain god, and the war god. The emergence of polytheism marked a significant moment in history. Prior to this religion, most people considered humans to be one of many creatures in the world. Polytheists increasingly believed the world to revolve around God and humans. In other words, humans were the highest life form, and gods oversaw human life. Everything else that lived was below humans.

- Monotheism — Monotheism is the belief in one God. Christianity and Islam are examples. Christianity began as a religion followed by a small group of Jews but spread quickly thanks to missionary work. It eventually took over the mighty Roman Empire, which primarily followed polytheism for most of its history. In 10 AD, there were hardly any monotheists. By 500 AD, Christianity had become the dominant religion in the Roman Empire and was spreading to Europe, Asia, Africa, and more. Today, monotheism is the type of religion most people in the world follow.

- Dualism — Dualistic religions posit the existence of two opposing powers: good and evil. Dualism explains that the entire universe is a battleground between these two forces and that everything that happens in the world is part of the struggle. Dualistic religions flourished for more than 1,000 years and were widely adopted in the Persian Empire during the years 550-330 BC.

- The Law of Nature — These are religions such as Buddhism, Stoicism, and Confucianism. These religions are characterized by their disregard of gods. These creeds posit that the laws of nature are in control of the world and its creatures, not any kind of divine god or gods.

- Monotheism & Christianity — What’s interesting about Christianity and other types of monotheistic religions is that there’s an overarching belief in one God, and that makes it hard to explain the evil in the world. If God is responsible for keeping people safe and healthy, how do you explain all of the awful, evil things that go on? Many Christians point to an independent Devil. But the existence of a Devil contradicts the monotheistic belief in one single supernatural figure. Many Christians also believe in a heaven and a hell. This is also dualistic in nature. Monotheistic religions like Christianity therefore act more like dualistic religions.

- Buddhism — Buddhism is one of the “laws of nature” religions or creeds. The central figure of Buddhism isn’t a god but a human being, Siddhartha Gautama. Gautama is believed to have spent many years in search of why humans are constantly dissatisfied and how to overcome it. He eventually found the reason and figured out ways to reduce suffering of the mind. Through his practice and teachings, he became the Buddha. Buddhism does not deny the existence of gods — they just aren’t seen as all-powerful forces.

- Quote (P. 24): “At the age of 29, Gautama slipped away from his palace in the middle of the night . . . He traveled as a homeless person through India, searching for a way out of suffering . . . He spent six years meditating on the essence, causes, and cures for human anguish. In the end he came to the realization that suffering is not caused by ill fortune, by social injustice, or by divine whims. Rather, suffering is caused by the behavior patterns of one’s own mind. Gautama’s insight was that no matter what the mind experiences, it usually reacts with craving, and craving always involves dissatisfaction . . . Gautama found that there was a way to escape this vicious circle. If, when the mind experiences something pleasant or unpleasant, it simply accepts things as they are, then there is no suffering.”

- Quote (P. 226): “But how do you get the mind to accept things as they are, without craving? To accept sadness as sadness, joy as joy, pain as pain? Gautama developed a set of meditation techniques that train the mind to experience reality as it is, without craving. These practices train the mind to focus all its attention on the question, ‘What am I experiencing now?’ rather than on ‘What would I rather be experiencing?’ . . . When the flames are completely extinguished, craving is replaced by a state of perfect contentment and serenity, known as nirvana (the literal meaning of which is extinguishing the fire). Those who have attained nirvana are fully liberated from all suffering. They experience reality with the utmost clarity, free of fantasies and delusions. While they will most likely still encounter unpleasantness and pain, such experiences cause them no misery. A person who does not crave cannot suffer.”

- Quote (P. 226): “According to Buddhist tradition, Gautama himself attained nirvana and was fully liberated from suffering. Henceforth he was known as ‘Buddha’, which means ‘The Enlightened One’. Buddha spent the rest of his life explaining his discoveries to others so that everyone could be freed from suffering. He encapsulated his teachings in a single law: suffering arises from craving; the only way to be fully liberated from suffering is to be fully liberated from craving; and the only way to be liberated from craving is to train the mind to experience reality as it is.”

- Chapter Takeaway — Religion was the third force that helped unify our world. Polytheism was one of the first forms of religion that gained widespread popularity, including in the Roman Empire. Forms of monotheistic religion, like Christianity, later became dominant and eventually became the preferred religion in the Roman Empire.

Ch. 14: The Discovery of Ignorance

- Explosive Growth — The last 500 years have witnessed the most rapid and explosive growth in human power. In the year 1500, there were 500 million Sapiens. Today, there are more than 7 billion. The total value of goods and services produced in the year 1500 was $250 billion in today’s dollars. Today, an average year of production is $60 trillion. The last 500 years have seen humans land on the moon, build and drop an atomic bomb, create the Internet, build the airplane, release the iPhone, and more. We have experienced breath-taking growth in almost every area of life over the last 500 years. Somebody living in the year 1000 who woke up in 1500 wouldn’t have noticed much of a change. But somebody living in 1500 who woke up in 2020 would feel like they were on another planet.

- The Scientific Revolution — Why have we experienced incredible growth over the last 500 years? The answer involves science and technology. We have invested tremendous resources into scientific research, which has led to many of the major successes we’ve had. The author calls this period the Scientific Revolution — the third major revolution in the history of Sapiens alongside the Cognitive Revolution and Agricultural Revolution. During it, we have developed new weapons and modes of transportation, created new medicines, and stimulated booming economic growth. Prior to this period, rulers and people in power didn’t spend their money on scientific research. That has changed over the last five centuries. We have come to terms as a species that we don’t know very much, and that willingness to admit ignorance is what sparked the Scientific Revolution around the year 1500.

- Quote (P. 249): “The typical premodern ruler gave money to priests, philosophers and poets in the hope that they would legitimize his rule and maintain the social order. He did not expect them to discover new medications, invent new weapons, or stimulate economic growth. During the last five centuries, humans increasingly came to believe that they could increase their capabilities by investing in scientific research.”

- Quote (P. 251): “The great discovery that launched the Scientific Revolution was the discovery that humans do not know the answers to their most important questions.”

- Quote (P. 253): “The willingness to admit ignorance has made modern science more dynamic, supple, and inquisitive than any previous tradition of knowledge. This has hugely expanded our capacity to understand how the world works and our ability to invent new technologies.”

- Interesting Fact — In 1620, Francis Bacon published a scientific manifesto called The New Instrument. In it, he argued that “knowledge is power.” This is where that saying comes from.

- Interesting Fact — In 1687, Isaac Newton published The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. It is considered one of the most important books in modern history because in it he presented his thoughts on gravity. His theories helped scientists predict the movement of all bodies of the universe, from falling apples to shooting stars, using three mathematical laws. Toward the end of the 1800s, scientists like Albert Einstein found a few issues with Newton’s laws and expanded his ideas with quantum mechanics and the theory of relativity.

- Purposeful Science — What sparked the Scientific Revolution was a newfound devotion to purposeful science. Before the year 1500, rulers built educational institutions, but those institutions were designed to teach traditional knowledge. Once in a while, somebody would come up with a better piece of technology, but these were usually created by uneducated craftsman who were tooling around, not by scholars pursuing systematic scientific research. That has all changed in the last 500 years. Colleges and military institutions around the world are now completely focused on creating better technology, medicine, and weapons. Science and technology were crucial in WWI and WWII (e.g. Manhattan Project and the atom bomb that ended the war).

- Quote (P. 260): “When World War One bogged down into interminable trench warfare, both sides called in the scientists to break the deadlock and save the nation. The men in white answered the call, and out of the laboratories rolled a constant stream of new wonder-weapons: combat aircraft, poison gas, tanks, submarines, and ever more efficient machine guns, artillery pieces, rifles and bombs.”

- Quote (P. 261): “While the Germans were working on rockets and jets [in WWII], the American Manhattan Project successfully developed atomic bombs.”

- Obsession With Technology — Our obsession with military technology, from tanks to atom bombs to spy-flies, is a surprisingly recent trend. Again, rulers from centuries ago were not fixated on science and tech. Military units in the Roman Empire and those led by Napoleon, for example, instead relied on manpower, discipline, strategy, and execution to win. Everybody for the most part fought with the same technology and weapons. Today, every nation is obsessed with developing new technology in order to gain an advantage. It’s an arms race.

- Quote (P. 262): “Most empires did not rise thanks to technological wizardry, and their rulers did not give much thought to technological improvement.”

- Medicine & Eternal Life — Another hallmark of the Scientific Revolution has been our focus on medicine and increasing the human lifespan. In addition to creating new weapons and technology, our scientists are busy figuring out ways to develop new medicines, revolutionary treatments, and artificial organs that will lengthen our lives and possibly give eternal life one day. Prior to the past 500 years, elites were running around trying to give meaning to death. Today, we’re focused on prolonging it. The strides we’ve made over the last 200 years alone have been huge.

- Quote (P. 268): “Pills, injections, and sophisticated operations save us from a spate of illnesses and injuries that once dealt an inescapable death sentence. They also protect us against countless daily aches and ailments, which premodern people simply accepted as part of life. The average life expectancy jumped from well below twenty-five to forty years, to around sixty-seven in the entire world, and to around eighty years in the developed world.”

- Interesting Fact — The first anesthetics — ether, chloroform, and morphine — didn’t enter regular usage in Western medicine until the mid-nineteenth century. Before the invention of chloroform, soldiers had to hold down a wounded comrade while the doctor sawed off the injured limb.

- Interesting Fact — The death rate among children and babies used to be alarmingly high. Until the 1900s, 25% of children never reached adulthood. Most succumbed to childhood diseases like measles and smallpox. An example of how bad this used to be is the family of King Edward I of England and his wife, Queen Eleanor. they lived in the 1200s. They had 16 children together — 10 of them died during childhood. These children were born into the perfect set of conditions at the time, and they still died. Today, almost all babies and children live to adulthood. Advances in medicine have played a big role in that.

- Chapter Takeaway — The Scientific Revolution started 500 years ago and has led to huge advances in weapons, technology, and medicine. Driving these advances is our focus on purposeful science; some of our greatest minds are working in science, trying to figure out solutions to big issues. That wasn’t the case in the centuries prior to the year 1500. In those times, rulers and elites were focused on reinforcing “traditional” values among their people in order to sustain their empires.

Ch. 15: The Marriage of Science and Empire

- Europeans Dominate — From the year 1500 to 1850, Europe dominated during the Scientific Revolution period. The Europeans in Britain, Spain, France, Germany, etc. didn’t have any kind of technical advantage over those in Asia and the Middle East; they simply were more open-minded and willing to explore what they didn’t know. Unlike other parts of the world, they acknowledged that they didn’t know everything and that there was more to explore and discover. They invested in education. This was their secret. All of these efforts helped them gain new knowledge, explore new territories, and develop new techniques. All of this built-up knowledge helped them capitalize once advantages in technology began to appear in 1850.

- Quote (P. 254): “European imperialism was entirely unlike all other imperial projects in history. Previous seekers of empire tended to assume that they already understood the world. Conquest merely utilized and spread their view of the world. The Arabs, to name one example, did not conquer Egypt, Spain, or India in order to discover something they did not know. The Romans, Mongols and Aztecs voraciously conquered new lands in search of power and wealth — not of knowledge. In contrast, European imperialists set out to distant shores in the hope of obtaining new knowledge along with new territories.”

- Christopher Columbus — One of the highlights of European dominance was Christopher Columbus’s discovery of America. Columbus set sail from Spain in 1492 looking for a new route to Asia. In October of that year, Columbus and his team hit an unknown continent. Their initial collision point was in what we now call the Bahamas. Columbus believed he had reached a small island off the East Asian coast, and refused to acknowledge that he discovered new land. He was in denial because it was inconceivable to everybody on the planet at that time that there was new land yet to be discovered. It’s wild to think that only 500 years ago there were still parts of the world that were completely unknown to us.

- Why America Is Called America — Columbus was in denial about discovering a new continent. He thought he knew everything and didn’t want to appear ignorant. An Italian sailor named Amerigo Vespucci, who sailed to America several times from 1499-1504, argued in several papers that this was indeed a new continent, not some island off of East Asia like Columbus thought. In 1507, a respected mapmaker named Martin Waldseemuller published an updated world map that showed parts of the new continent to the west of Europe. With the new continent on the map, he had to give it a name. Because Columbus was not taking credit, Waldseemuller, who had read Vespucci’s papers, mistakenly believed it was Vespucci who discovered the continent. As a result, he named the continent America after Amerigo Vespucci.

- Discovery of America Ignites Europeans — The discovery of America is considered one of the greatest achievements during the Scientific Revolution. It not only reinforced Europe’s attitude about maintaining a curious mind, it also lit a fire under their butt to return there to conquer the land and learn as much as they could about the new area. The rest of the world was now way behind. People in Asia and the Middle East had no idea what was going on. And even when they did know that a new continent was out there, they made no effort to explore it, unlike the Europeans.

- Quote (P. 288): “The discovery of America was the foundational event of the Scientific Revolution. It not only taught Europeans to favor present observations over past traditions, but the desire to conquer America also obliged Europeans to search for new knowledge at breakneck speed. If they really wanted to control the vast new territories, they had to gather enormous amounts of new data about the geography, climate, flora, fauna, languages, cultures, and history of the new continent.”

- Spanish Empire Wins — Part of what made the Europeans so dominant in the 1500s was the success of the Spanish Empire. Led by Hernan Cortés, the Spanish Empire first went to the Caribbean Islands and conquered that area before traveling to Mexico to defeat the Aztec Empire. When the Spaniards arrived on the beaches of Mexico in 1519, they had 550 men compared to millions of people in the Aztec Empire. But Cortés found a way to take the leader of the Aztec Empire hostage and convince the people of Mexico to join him, leading to a win for the Spanish Empire. Ten years later, Spain traveled to the shores of the Inca Empire in the Peru area. They were victorious in taking down the Inca Empire despite having just 168 men.

- Laziness & Hubris — Part of what allowed the Europeans to be so successful in the early years of the Scientific Revolution was the laziness and hubris displayed by China, India, and the Middle East. The people in these areas simply showed no interest in exploring new areas and making progress in any realm of life. They thought they knew everything. They thought they were the only people in the world. The Aztec and Inca Empires in South America also thought this, which is why they lost to the Spanish Empire. The Europeans, on the other hand, were very ambitious and were honest with themselves about not knowing everything. Following the victories over the Aztec and Inca Empires, the Europeans invaded Asia and India and defeated their empires. In modern times, this is the equivalent of a company like BlockBuster failing to adapt and being defeated by Netflix, a company that was willing to explore new ways of doing things.

- Quote (P. 296): “The great empires of Asia — the Ottoman, the Safavid, the Mughal, and the Chinese — very quickly heard that the Europeans had discovered something big [discovery of America]. Yet they displayed little interest in these discoveries. They continued to believe that the world revolved around Asia, and made no attempt to compete with the Europeans for control of America or of the new ocean lanes in the Atlantic and the Pacific. Even puny European kingdoms such as Scotland and Denmark sent a few explore-and-conquer expeditions to America, but not one expedition of either exploration or conquest was ever sent to America from the Islamic world, India or China.”

- Quote (P. 291): “What made Europeans exceptional was their unparalleled and insatiable ambition to explore and conquer. Although they might have had the ability, the Romans never attempted to conquer India or Scandinavia, the Persians never attempted to conquer Madagascar or Spain, and the Chinese never attempted to conquer Indonesia or Africa. Most Chinese rulers left even nearby Japan to its own devices. There was nothing peculiar about that. The oddity is that early modern Europeans caught a fever that drove them to sail to distant and completely unknown lands full of alien cultures, take one step on to their beaches, and immediately declare, ‘I claim all these territories for my king!’”

- Chapter Takeaway — Europeans dominated the early years of the Scientific Revolution for two primary reasons: (i) they were more curious, open-minded, and ambitious than the rest of the world, and (ii) the rest of the world was kind of lazy and arrogant. The Europeans acknowledged that they didn’t know as everything there was to know. This attitude led them to invest in education, explore new areas, and focus on science. The people and empires in Asia, India, South America, and the Middle East were complacent and believed they knew everything there was to know.

Ch. 16: The Capitalist Creed

- Booming Economic Growth — Over the last 500 years, the Scientific Revolution — and the growth we’ve experienced as a species during it — has been driven by empires (previous chapter) and money. Our economy has grown like crazy over the last 500 years, which is not typical. For most of history, the economy has stayed about the same size. In the year 1500, global production of goods and services was equal to about $250 billion; today it hovers around $60 trillion. This growth has enabled us to fund various projects like the mission to the moon, Columbus’s exploration to America, and other scientific endeavors.

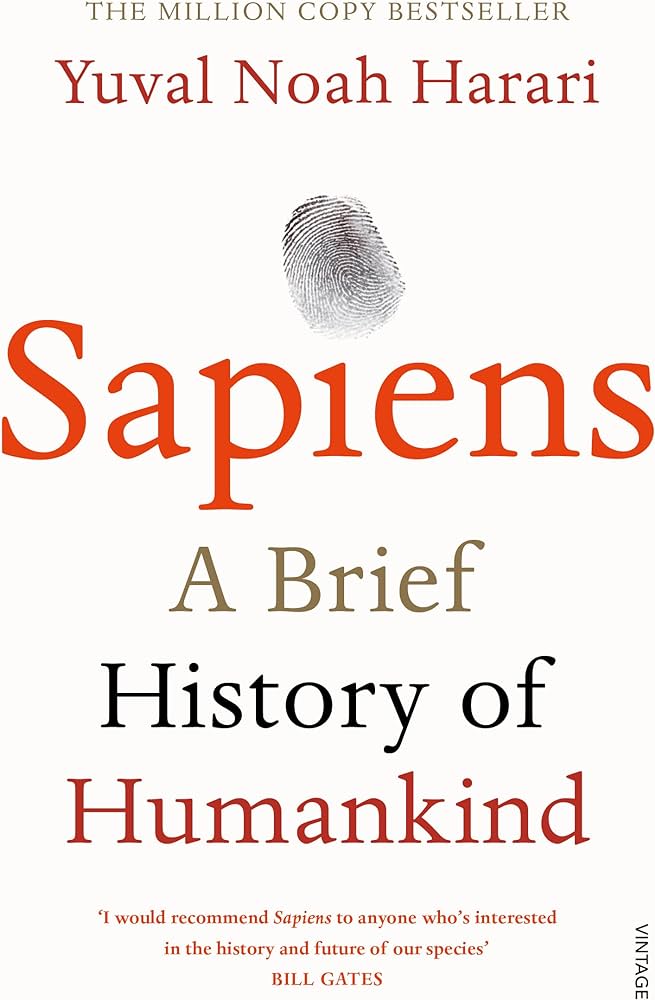

- The Rise of Credit — Why has our economy boomed over the last 500 years? The answer is a collective belief among humans that the future is bright, which in turn led to the use of credit. Prior to the last 500 years, people actually felt that the best days were behind us. There was no reason to give out loans and credit if there was little chance of being paid back. The only way kings could raise money to build palaces and wage wars was through heavy taxes and tariffs. But the Scientific Revolution period ushered in a whole new attitude — an attitude that there was more to learn and that progress was possible. This attitude of progress has led to a collective belief that our economy and wealth will continue to grow. Because banks and other people believed our economy would grow, they became more willing to lend credit to ordinary folks. Armed with loans and other forms of credit, ordinary people started opening their own businesses and other entrepreneurial endeavors. This cycle has led to explosive economic growth.

- Quote (P. 310): “Because credit was limited, people had trouble financing new businesses. Because there were few new businesses, the economy did not grow. Because it did not grow, people assumed it never would, and those who had capital were wary of extending credit.”

- Quote (P. 310): “Over the last 500 years the idea of progress convinced people to put more and more trust in the future. This trust created credit; credit brought real economic growth; and growth strengthened the trust in the future and opened the way for even more credit.”

- Interesting Fact — Banks are allowed to loan out $10 for every dollar they actually possess, which means that 90% of all the money in our bank accounts is phantom money that is not covered by actual paper currency and coins. If all of the account holders at Barclays Bank suddenly demand their money, Barclays will promptly collapse (unless the government steps in to save it).

- Capitalism For the Win — The idea of capitalism was popularized by the legendary economist Adam Smith in his book titled The Wealth of Nations published in 1776. Capitalist activities are ones in which business owners and ordinary folks invest the money they make from working in a way that leads to more money and helps the economy grow. Examples include a business owner using extra revenue to invest in more employees, or a regular worker putting part of his paycheck into the stock market. It’s about finding productive ways to put your money to use, whether that’s through expanding a business, investing in real estate, buying stock market shares, or something else. Capitalism drives our economy today, but it was a revolutionary idea in 1776. The rise of capitalism helped our economy grow. At the time, few people believed in reinvesting profits to increase economic production. Instead, rulers and elites threw their money into tournaments, palaces, wars, and cathedrals.

- Quote (P. 312): “A crucial part of the modern capitalist economy was the emergence of a new ethic, according to which profits ought to be reinvested in production. This brings about more profits, which are again reinvested in production, which brings more profits, et cetera ad infinitum.”

- Quote (P. 312): “In the new capitalist creed, the first and most sacred commandment is: ‘The profits of production must be reinvested in increasing production.’”

- Quote (P. 312): “That’s why capitalism is called ‘capitalism’. Capitalism distinguishes ‘capital’ from mere ‘wealth’. Capital consists of money, goods and resources that are invested in production. Wealth, on the other hand, is buried in the ground or wasted on unproductive activities. A pharaoh who pours resources into a non-productive pyramid is not a capitalist. A pirate who loots a Spanish treasure fleet and buries a chest full of glittering coins on the beach of some Caribbean island is not a capitalist. But a hard-working factory hand who reinvests part of his income in the stock market is.”

- Quote (P. 313): “In premodern times, people believed that production was more or less constant . . . Few tried to reinvest profits in increasing their manors’ output, developing better kinds of wheat, or looking for new markets.”

- Capitalism & Christopher Columbus — An example of how capitalism led to Europe’s dominance in the Scientific Revolution period is found in Christopher Columbus’s accidental discovery of America. The expedition that led Columbus to America in 1492 was financed by the Queen of Spain (Queen Isabella). Expeditions require a lot of money, and Columbus requested funds for the trip from several rulers in Europe — and all of them said ‘no’. Queen Isabella finally said ‘yes’, which turned out to be a great move. Columbus’s discovery allowed the Spaniards to conquer America, where they established gold and silver mines as well as sugar and tobacco plantations that made the Spanish kings, bankers, and merchants very wealthy. The discovery put Spain on top of the world at the time. But without capitalism and credit, Columbus never would have made the trip. Optimistic that Columbus could find something, Queen Isabella took a chance on the expedition and put her money on the line. This capitalist mindset was becoming favored over heavy taxation and tariffs.

- Quote (P. 316): “The European conquest of the world was increasingly financed through credit rather than taxes, and was increasingly directed by capitalists whose main ambition was to receive maximum returns on their investments.”

- Quote (P. 317): “Decade by decade, western Europe witnessed the development of a sophisticated financial system that could raise large amounts of credit on short notice and put it at the disposal of private entrepreneurs and governments. This system could finance explorations and conquests far more efficiently than any kingdom or empire.”

- Capitalism: Spain vs. the Netherlands — Another example of the power of capitalism is observed in the back and forth between Spain and the Netherlands. During the 1500s, Spain was the top dog, ruling vast territories across Europe, the Americas, Asia, and Africa. The Netherlands, then under Spanish control, revolted in 1568, leading to a prolonged conflict known as the Dutch Revolt. Despite being much smaller, the Dutch won their independence by 1648 and established the Dutch Republic, which soon became one of the wealthiest and most powerful states in Europe. A key factor in their success was their innovative use of credit and early capitalist practices. Examples of how they leveraged capitalism include:

- A Good Place to Invest — The Dutch developed a sophisticated financial system, repaying loans and providing solid returns on investments, which earned them the trust of European financiers. This financial stability allowed them to fund armies, build fleets, and dominate global trade routes. In contrast, Spain faced financial difficulties, including repeated bankruptcies and economic mismanagement, which hampered its ability to sustain its empire. Thanks to their focus on capitalism and credit, the Netherlands simply became a better place to invest money than Spain, which allowed them to borrow more money at lower interest rates from financiers across Europe. This was a key factor in their success.

- Inventing the Stock Market — The Dutch established the Amsterdam Stock Exchange in 1602, often considered the world’s first official stock exchange, and the Dutch East India Company (VOC) became one of the first multinational corporations. The VOC used the money it raised from selling shares to build ships, send them to Asia, and bring back Chinese, Indian, and Indonesian goods. Eventually VOC money financed the conquest of Indonesia.

- New Amsterdam & Wall Street — In order to control trade on the important Hudson River (in New York), the Netherlands built a settlement called New Amsterdam at the southern tip of Manhattan Island. New Amsterdam was threatened by Native Americans and repeatedly attacked by the British, who eventually captured it in 1664. The British changed its name to New York. The remains of the big wall built by the Dutch to defend New Amsterdam against Native Americans and British are today paved over by the world’s most famous street — Wall Street. The protective wall the Dutch built to protect themselves is where Wall Street gets its name.

- The First Opium War — The British and Chinese fought each other in what was called the First Opium War (1840-42). In the early 1800s, the British were making a fortune by exporting opium from India to China. Millions of Chinese became addicts, which hurt the country economically and socially. In the 1830s, the Chinese, under the Qing Dynasty, issued a ban on drug trafficking, but the British refused to comply. This led the Chinese to confiscate and destroy drug cargos. In 1840 the British declared war in the name of “free trade.” The British won easily. In the peace treaty, the Chinese agreed to let Britain resume importing opium and they gave Hong Kong to the Brits. By the late 1800s, 40 million Chinese people were opium addicts. Hong Kong remained under British control until 1997.

- It’s All About Trust — As we’ve learned in this chapter, a crucial economic resource for any country to have is collective trust in a positive future. If people don’t believe that the future is bright, they are not going to spend money in the economy, invest in the stock market or real estate, or open businesses. There was a lack of trust in the global economy prior to the year 1500, and that is one of several reasons why the economy stayed the same size for most of history. Over the last 500 years, there has been a complete reversal — people now believe in progress. They believe that good things are ahead. That belief has inspired them to use credit and borrow money, which has enabled the economy to expand significantly. You can even see this trust factor in play at a micro level by looking at the stock market; when stocks are down for a while, it’s because people don’t trust what’s going on. They’re hesitant. When stocks are doing really well, it’s because people are optimistic and believe that good things are ahead.

- We’re Lucky — Reading this book and others like it this year has opened my eyes to the fact that we are living in the best time period in the history of our species. The comfort and convenience that we live with every day is unlike anything humans have ever experienced. Living conditions 200, 300, 400, 500 years ago and beyond (imagine 10,000 years ago!) were far, far less favorable. Our ancestors were absolute warriors. We are so lucky to be living in this time period, and we shouldn’t take it for granted. The growth we’ve experienced as a species over the last 500 years has been incredible in every area of life. We’re truly living in a dream.

- Chapter Takeaway — The rise of credit and capitalism has been one of the driving forces behind our explosive growth as a species over the last 500 years. Capitalism and credit rose to prominence largely because many areas of the world went from believing that there was no point in trying to grow, to a real belief that progress was possible. This mindset led to new businesses, scientific explorations, research efforts, and more.

Ch. 17: The Wheels of Industry

- The Industrial Revolution — The Industrial Revolution began about 250 years ago. Although capitalism and trust in the future (discussed in previous chapter) were key factors in our explosive growth over the last five centuries, the Industrial Revolution was critical as well because economic growth requires energy and raw materials. The Industrial Revolution is characterized by our ability to harness energy and convert it into mass production. It was also a period where we became very good at creating raw materials used for building things, which fueled the manufacturing and construction sectors, leading to huge advancements in our economy and society.