Misbehaving

Richard Thaler

GENRE: Business & Finance

GENRE: Business & Finance

PAGES: 432

PAGES: 432

COMPLETED: May 1, 2022

COMPLETED: May 1, 2022

RATING:

RATING:

Short Summary

Blending recent discoveries in human psychology with a basic understanding of economics, Richard Thaler — A Nobel Prize winner in Economics — shows readers how to make smarter decisions in an increasingly mystifying world. He reveals how behavioral economic analysis opens up new ways to look at just about anything.

Key Takeaways

Favorite Quote

"They can be changes from the status quo or changes from what was expected, but whatever form they take, it is changes that make us happy or miserable."

Book Notes

Ch. 1: Supposedly Irrelevant Factors

- Author Richard Thaler is an economist and a professor at the University of Chicago School of Business.

- His area of specialty is behavioral economics.

- Misbehaving — When the behavior of humans deviates from the idealized model of behavior in economic theory.

- In other words, when people’s behavior doesn’t follow the expected behavior predicted by economic theories.

- Humans misbehave a lot, which can make many economic models very bad at predicting outcomes.

- Misbehaving was one of the factors that caused The Great Recession of 2007-08. Very few economists saw it coming.

- Ex. Thaler’s Students — When Thaler gave his first test, the average score was a 73/100 (73%). Despite being graded on a curve, students were unhappy. On the next test, he made it 137 total points and the average score was 96/137 (70%). The students were delighted. The appearance of a high 90s score, for some reason, made students happy even though the average score as a percentage came out lower than the first test.

- Two Core Components of the Economic Model of Behavior Theory

- Constrained Optimization — People will choose the best option(s) available to them given their budget.

- Equilibrium — Supply and demand drive prices in a competitive, free market.

- Optimization + Equilibrium = Economics

- The issue with the economic model of behavior — and specifically constrained optimization — is that there are so many options available to the average person. These millions of options make it very difficult to select the most optimal choice(s).

- But the economic model of behavior assumes that people always make the most optimal choice.

- Ex. Grocery Store — A family is faced with a ton of choices within their budget. It’s rare that they select the truly most optimal collection of foods on the trip.

- Economists have a big impact on public policy. Their predictions and findings are used frequently.

- Not good when many of their predictions are based on people optimizing.

- Behavioral Economics — Fuses theories of psychology and economics to predict economic behavior.

- An up-and-coming branch of economics that is being fueled by a younger generation of economists.

- It attempts to factor in real human behavior, rather than pretending that humans will act as robots.

- Thaler is one of the people who has made behavior economics a relevant branch. This book discusses his journey.

Ch. 2: The Endowment Effect

- Opportunity Cost — What you give up by engaging in a certain activity.

- Ex. Time — If I decide to go for a hike on a Sunday morning in October, my opportunity cost is watching NFL games, or reading, or lifting weights, etc.

- The Endowment Effect — People value things they already own more highly than things they could own but have not acquired yet.

- Framing — How things are framed and presented has a big influence on human behavior.

- Ex. Credit Card Charges — When credit cards were becoming big, credit card users and retailers entered a legal battle over whether merchants could charge different prices to cash and credit card customers. Credit card companies charge retailers for collecting the money, so many merchants wanted to charge more for a customer to use a credit card. As the case went through the legal system, the credit card companies decided it was OK for merchants to charge different prices, as long as they framed the higher credit card price as the ‘regular price’ and the lower cash price as a ‘discount.’ The opposite frame job would have been to say that the lower cash price was the ‘regular price’ and the higher credit card was an ‘additional surcharge.’ In both cases, the prices are the same for credit card use vs. cash use, but it is framed to the customer differently, and this framing has a huge impact human decision-making. If they have to pay the ‘additional surcharge’ to use their credit card, they may be less likely to use it. But if they just have to pass up on paying the cash ‘discount’ price in order to use their credit card, they are more likely to still use the credit card.

Ch. 3: The List

- Hindsight Bias — After the fact, we think we always knew the outcome was likely, if not certain.

- Managers at companies worry about this. They worry that if they start a project and it doesn’t go well, the CEO will conclude that whatever the cause of the failure was, it should have been anticipated ahead of time.

- Early on in his time as a graduate student at the University of Rochester, Thaler began to see frequent examples of human behavior not fitting traditional economic theories. It sparked his curiosity.

- He wrote down some of these examples in what he called The List.

- Thaler later stumbled on the work of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, who together wrote an important paper called Judgement Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases.

- The paper’s thesis was that humans have limited time and brainpower. As a result, we use simple rules of thumb (heuristics) to help us make judgements.

- These judgements lead to biases that influence our decision-making.

- The paper helped explain that errors found in economic models are not random, which was the assumption in traditional economics at the time.

- This paper was huge for Thaler. It helped him understand that errors in economic theory are caused by irrational human behavior.

- The paper’s thesis was that humans have limited time and brainpower. As a result, we use simple rules of thumb (heuristics) to help us make judgements.

Ch. 4: Value Theory

- 2000 — Thaler gets an early copy of Kahneman and Tversky’s iconic paper called Prospect Theory.

- The findings in this paper led to Kahneman winning a Nobel Prize in 2002. The findings:

- We experience life in terms of changes.

- We feel diminishing sensitivity to both gains and losses.

- Losses sting more than equivalently-sized gains feel good.

- The findings in this paper led to Kahneman winning a Nobel Prize in 2002. The findings:

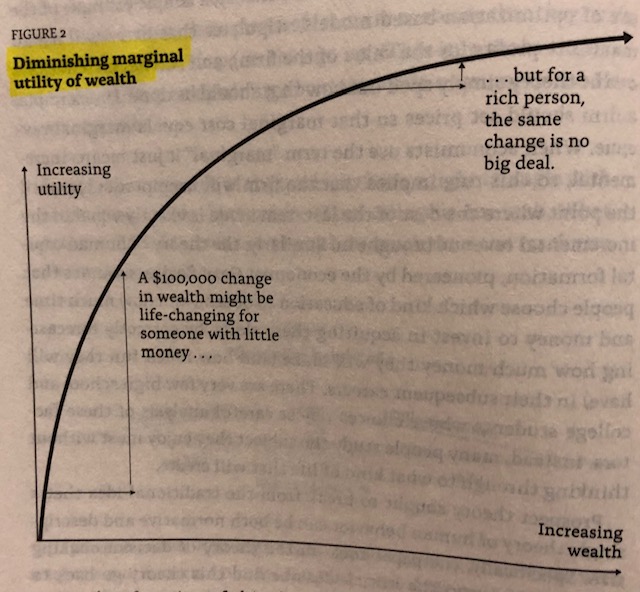

- Diminishing Sensitivity — Our happiness (or utility, as economists call it) increases as we get wealthier, but at a diminishing rate.

- As we make more money, every bump in wealth has less of an impact on our overall happiness.

- Ex. $100,000 to someone who really needs money is life-changing. But $100,000 to Bill Gates is hardly noticeable.

- 1778 — Daniel Bernoulli first introduced this concept, as well as a related idea called risk aversion. He helped create the following graph on diminishing marginal utility:

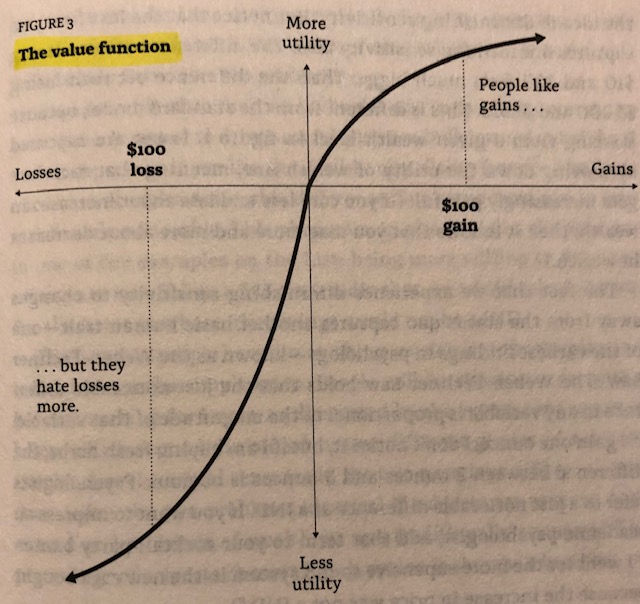

- Kahneman and Tversky elevated Bernoulli’s concept of diminishing sensitivity by focusing on changes in wealth vs. levels of wealth.

- They focused on changes in wealth because changes are the way humans experience life.

- Ex. Temperature — If you are in your office at one temperature and move into a different conference room to take a meeting and the temperature is different (hot or cold), you will notice that change.

- Quote (P. 31): “They can be changes from the status quo or changes from what was expected, but whatever form they take, it is changes that make us happy or miserable.”

- They focused on changes in wealth because changes are the way humans experience life.

- Loss Aversion — Losses hurt about twice as much as gains make you feel good.

- We feel losses more significantly than we feel gains.

- This is illustrated in the value function chart below. The decline line is twice as steep as the gain line.

- Loss aversion means we are scared to lose things. We don’t like to lose.

- This is the most powerful tool in behavioral economics.

- We feel losses more significantly than we feel gains.

Ch. 5: California Dreamin'

- 1977 — Thaler spent a year at Stanford University working with Kahneman and Tversky, who were there finishing up their Prospect Theory paper.

- It was during this time at Stanford that Thaler decided to go all in on behavioral economics.

Ch. 6: The Gauntlet

- 1978 — Thaler accepts a teaching position at Cornell.

- At Cornell, Thaler began to talk about behavioral economics at conferences. His talks were met with a lot of skepticism from traditional economists, most of whom didn’t believe in this stuff.

- He knew he had to begin to produce some actual research to back up his hunches.

- At Cornell, Thaler began to talk about behavioral economics at conferences. His talks were met with a lot of skepticism from traditional economists, most of whom didn’t believe in this stuff.

- Marginal Analysis — A firm striving to maximize profits will set price and output at the point where marginal cost equals marginal revenue.

- Applies to hiring as well — keep hiring workers until the cost of the last worker equals the increase in revenue that the worker produces.

- This is one of the traditional economic models.

- Most places don’t follow this model though. Most places try to sell as much of a product as possible and hire the required number of workers to meet that demand level.

- Two ingredients are needed to learn from experience:

- Frequent Practice

- Immediate Feedback

- Because learning takes practice, we are more likely to get things right at small stakes than at high stakes.

- Ex. We’re more likely to do a great job washing our car than buying a new car. We wash our car frequently. We don’t buy new cars often. Many people argue the opposite — the greater the stakes, the more incentive we have to take our time, make a greater effort, and get it right.

- Because learning takes practice, we are more likely to get things right at small stakes than at high stakes.

Ch. 7: Bargains and Rip-Offs

- Mental Accounting — A concept in behavioral economics that studies how people think about money.

- Most of Thaler’s work pertains to this subject.

- Basic Economic Theory of the Consumer — Financial expenditures don’t fully explain the cost of one item or activity. It’s also about opportunity costs.

- Ex. If you have a ticket to a basketball game that you spent $500 for, the cost of going to the game is not simply $500. You also should factor in what you COULD be doing with that time and money instead.

- We should think in terms of opportunity costs more often (and this is how traditional economics think), but the typical consumer does not think like this.

- Acquisition Utility — The surplus remaining after we measure the utility of the object gained and subtract the opportunity cost of what has to be given up.

- Utility is an economics term that means happiness.

- Object Utility — Opportunity Cost = Acquisition Utility

- This concept is called ‘consumer surplus’ by traditional economists.

- For traditional economists, this is the end of the story — a purchase will produce a surplus of utility if a consumer values something more than the marketplace.

- But humans also factor in the quality of the deal, which is what transaction utility measures.

- Transaction Utility — Difference between the price actually paid for the object and the price one would normally expect to pay (the reference price).

- Bargains and rip-offs.

- This concept has a lot to do with consumer expectations.

- One study found that people were willing to pay more for beer from a resort than from a regular convenience store.

- Beer at a hotel is expected to be more expensive by the consumer so they were willing to pay more for it from that location compared to what they were willing to pay for the same beer from a convenience store.

- People were willing to pay $5 for a beer from the resort (and felt it was a steal) because they expected it to be at least $7. Meanwhile, they were not willing to pay $5 for the same beer from the convenience store because they expected it to be no more than $4.

- Beer at a hotel is expected to be more expensive by the consumer so they were willing to pay more for it from that location compared to what they were willing to pay for the same beer from a convenience store.

- Because consumers think in line with the concept of Transaction Utility, sellers have an incentive to manipulate the perceived reference price and create an illusion of a ‘deal’ to entice buyers.

- Sellers will list an item’s ‘suggested retail price’ as a way to give a misleading reference price.

- Consumers then see the ‘suggested retail price’ and assume they are getting a good deal.

- In reality, items that are on sale a lot (like rugs and mattresses) usually don’t sell well and aren’t a ‘deal’ at all.

- Sellers will list an item’s ‘suggested retail price’ as a way to give a misleading reference price.

- Finding ‘deals’ has been shown to be an addictive consumer behavior.

- People love perceived deals.

- When places like Macy’s and JC Penney tried to stop using coupons in favor of just pricing everything fairly in 2012, it did not go over well with consumers. Sales and stock price plummeted.

- People like to feel like they are getting a deal. They like to feel Transaction Utility.

- JC Penney CEO Ned Johnson was later fired and the company returned to coupons.

- One 2012 study found that businesses that offered deals to consumers did better than those who didn’t when a Walmart was built in the town.

- Chapter Takeaway — For businesses, understand that the lure of a deal will attract customers. For consumers, don’t get tricked into buying something you’ll never use just to secure a good bargain. Often, the ‘bargain’ is a myth.

Ch. 8: Sunk Costs

- Sunk Costs — When an amount of money has been spent and cannot be retrieved.

- Ex. Gym Membership — If you buy a monthly membership and don’t go regularly.

- We tend to use products — even when we don’t necessarily want to — in order to justify our purchases. If we buy something and don’t use it, we feel like we’ve taken a big loss.

- Ex. Clothes — If you buy certain clothes and hardly ever wear them. The money has already been spent. There’s no point in trying to force yourself to wear them if you don’t want to, but we tend to do exactly that because we feel that we have to justify the purchase.

- Ex. Gym Membership — There was a study that showed people go to the gym more frequently right after being billed for the month, and their attendance drops off significantly as the month goes on. This illustrates the idea of sunk costs — people feel like they have to justify their monthly payment to themselves so they go to the gym a lot after being billed.

- Chapter Takeaway — We tend to justify our purchases by using the product or service, even when we don’t really want to. The better idea is to just accept that the money has been spent on the product or service already and using it against your will isn’t going to change that.

- Memberships (Amazon Prime, Costco, etc.) take advantage by requiring monthly or yearly payments for the membership. Users then feel compelled to use the membership and buy things at Amazon or Costco to justify the monthly or yearly purchase.

Ch. 9: Buckets and Budgets

- Most people approach budgets by thinking in terms of categories.

- Ex. Entertainment budget, food budget, clothes budget, ect.

- People will stick closely to the allotted budget for each category.

- Ex. Entertainment budget, food budget, clothes budget, ect.

- Money is Fungible — Another traditional economic theory that says there are no labels restricting where money can be spent.

- Ex. If you have extra money in your clothes budget because you haven’t bought clothes recently, it can easily go to entertainment.

- But that’s not how we behave!

- One study found that people increased the amount of money they spent on gasoline during The Great Recession of 2007-08.

- Gas prices decreased significantly during this time, but instead of spending the excess money in their gas budget on other things, the study found that many people spent the money by upgrading to Premium fuel.

- Ex. If you have extra money in your clothes budget because you haven’t bought clothes recently, it can easily go to entertainment.

- Chapter Takeaway — Setting up non-fungible budget buckets is a good way to live within your means. But sometimes it causes us to make weird decisions, like upgrading to Premium fuel during a recession.

Ch. 10: At the Poker Table

- House Money Effect — When people win additional money above their cost basis — by gambling or investing — they will tend to be more loose and take more risks with that cash.

- They feel like they are playing with ‘house money.’

- What fuels this behavior is that they feel, worst case scenario, they’ll go back to even.

- I have noticed this tendency in my own behavior.

- This tendency really shouldn’t be the case. You should feel the need to protect your gains.

- On the other hand, people who have lost money and have a chance to break-even, will be usually willing to take risks.

- Ex. Sports Gambling — Rather than accepting your losses, the tendency is to want to get back to even by putting bets on heavy favorites.

- Ex. Fund Managers — At the end of the year, many mutual fund managers have been known to take a lot of risks in the last quarter when their fund is trailing the S&P 500 Index, which the fund manager is usually measured against.

- Chapter Takeaway — People take more risks and are less risk averse when they are playing with gains, or ‘house money.’ Meanwhile, people who have lost money but have a chance to break-even will take more risks to try to get there.

Ch. 11: Willpower? No Problem

- Discounted Utility Model — States that consumption is worth more to you now than later.

- We all discount future consumption at some rate.

- Ex. If given the choice between a great dinner this week or one a year from now, most people will prefer the dinner sooner than later. If a dinner a year from now is only considered to be 90% as good as one right now, we are said to be discounting the future dinner at an annual rate of about 10%.

- Developed by one of the great economists ever, Paul Samuelson in 1937.

- It remains a highly used and a standard formulation today.

- We all discount future consumption at some rate.

- The Consumption Function — Shows how the spending of a household varies with its income.

- John Maynard Keynes, Milton Friedman, and Franco Modigliani each came up with models to try to explain how a household will spend money.

- Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC) — Keynes argued that a household will consume a fixed amount of some additional infusion of income (say, $1,000) depending on how wealthy it is. If the household is relatively poor, it would spend most of the $1,000. If the household was middle-class and above, the additional income would not affect consumption very much at all.

- Permanent Income Hypothesis — Friedman argued that households will consume the additional income over the course of a three-year period. So a middle-class and above family would spread the $1,000 spending over three years ($333).

- Life-Cycle Hypothesis — Modigliani argued that people would determine a plan when young about how to spend their consumption over their lifetime, including retirement. So, people would have a plan for how to spend lifetime income. They would allow this plan to dictate their spending habits over their lifetime. In this model, the additional $1,000 would be spread over a 40-year horizon ($25 per year would be consumed).

- All three of these models become more planned out and strict with each entry. Modigliani’s model assumes extreme self-control and intelligence, and humans are just not that way. That’s why these models are not the best predictors of behavior — they don’t factor in the human element.

- Quote (P. 98): “To understand the consumption behavior of households, we clearly need to get back to studying humans rather than econs. Humans do not have the brains of Einstein, nor do they have the self-control of a Buddhist monk. Rather, they have passions, treat various parts of wealth quite differently, and can be influenced by short run returns in the stock market.”

- John Maynard Keynes, Milton Friedman, and Franco Modigliani each came up with models to try to explain how a household will spend money.

- Chapter Takeaway — People value current pleasure more than future pleasure. And we all spend money differently. Many traditional economic models don’t do a great job of factoring in human behavior.

Ch. 12: The Planner and the Doer

- Commitment Strategy — When we prevent ourselves from making a poor decision by removing the option entirely.

- Ex. Food — If you have a bag of chips next to you, the best way to prevent yourself from overeating is to put the bag away in a cabinet. Eliminate the option to keep eating more chips.

- You could alternatively put a handful of chips in a bowl. In this scenario, you would be done when you ate your last chip out of the bowl.

- Ex. Food — If you have a bag of chips next to you, the best way to prevent yourself from overeating is to put the bag away in a cabinet. Eliminate the option to keep eating more chips.

- Planner-Doer Model — Created by Thaler, this model explains that we have two selves, a ‘planner’ and a ‘doer’ that are always butting heads with each other. It’s a model that attempts to explain the self-control problems humans have.

- Planner — Has good intentions and cares about the future. System 2.

- Doer — Only cares about the needs and impulses in the current moment. System 1.

- Self-control comes down to a conflict between these two selves — the planner is concerned with the future and the doer only cares about the satisfaction of the current moment.

- Quote (P. 108): “Another way to think about this is that employing willpower requires effort.”

- Rules and commitment strategies are how we keep ourselves in line. But these require effort.

- Hot-Cold Empathy Gaps — When we are in a ‘cold’, relaxed mood, we predict that we will exhibit self-control. But when the actual moment of self-control comes, we often give in to our ‘hot’ impulses.

- Ex. Diet — Bob says he will stick to his diet all week and eat healthy foods. But when a coworker suggests going out to get pizza on Wednesday night, Bob gives in and eats a ton of pizza and calories.

- Rules and commitment strategies are needed to prevent scenarios like this from occurring.

- Ex. Diet — Bob says he will stick to his diet all week and eat healthy foods. But when a coworker suggests going out to get pizza on Wednesday night, Bob gives in and eats a ton of pizza and calories.

- Chapter Takeaway — Self-control comes down to a conflict between what we want right now and what our ‘planner’ knows we need to actually do.

Ch. 13: Misbehaving in the Real World

- Thaler noticed some of the ideas discussed in previous chapters show up in real life.

- Greek Peak — Thaler helped the owners of Greek Peak Slopes in New York get out of debt by strategically raising prices and offering ‘deals’ to consumers.

- Thaler helped form pricing strategies and package deals that enticed customers to sign up for ski passes at the start of ski season.

- Thaler was targeting Transactional Utility. He wanted customers to feel like they were receiving a deal with some of these strategies.

- The focus was also on increasing the customer experience by making some enhancements to the ski resort. This justified the price increases.

- The strategies worked. Over a three-year period, the resort came out of debt.

- General Motors — The iconic car company was trying to sell more old inventory as new models came out every year. The company decided to offer the option of a rebate or a 2.9% loan on a new car. The prevailing car loan rate at the time was 10%.

- When the company offered the loan, sales went up like crazy. Getting a 2.9% loan compared to a 10% loan seemed like a great deal on the surface.

- In reality, the rebate actually was the better deal. Someone with The Wall Street Journalhad done the math and figured that out. But a relatively small discount towards a new purchase didn’t seem as great as a significant loan reduction.

- Transactional Utility was in play here as well.

- Greek Peak — Thaler helped the owners of Greek Peak Slopes in New York get out of debt by strategically raising prices and offering ‘deals’ to consumers.

- Chapter Takeaway — The ideas of behavioral economics can be observed everywhere.

Ch. 14: What Seems Fair

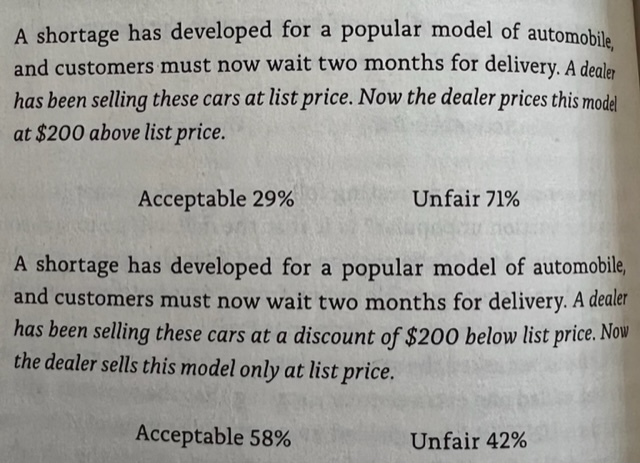

- How something is framed plays a big role in how ‘fair’ it comes across to a consumer.

- Ex. Dolls — One survey asked respondents whether it was ‘acceptable’ or ‘unacceptable’ for a store to auction off its last Cabbage Patch doll to the highest bidder after the store had already sold out of this hot product. 74% of respondents said it was ‘unacceptable’, while 26% said it was ‘acceptable.’

- When the same question was asked to respondents, but with an added line about how the proceeds of the auction will go to charity, 79% of respondents said the auction was ‘acceptable.’

- Ex. Dolls — One survey asked respondents whether it was ‘acceptable’ or ‘unacceptable’ for a store to auction off its last Cabbage Patch doll to the highest bidder after the store had already sold out of this hot product. 74% of respondents said it was ‘unacceptable’, while 26% said it was ‘acceptable.’

- Quote (P. 131): “Any firm should establish the highest price it intends to charge as the ‘regular’ price, with any deviations from that price called ‘sales’ or ‘discounts.’ Removing a discount is not nearly as objectionable as adding a surcharge.”

- Set a high reference point and then work down. The high reference point makes everything under it seem like a deal to the consumer.

- Ex. Cars — See picture

- Quote (P. 131): “Perceptions of fairness are related to the Endowment Effect.”

- The Endowment Effect states that we hate losing what we already have.

- The status quo is the reference point. Any changes to the status quo makes us feel like we’re being treated unfairly.

- Ex. Stone and Vine Italian Restaurant in Phoenix, AZ — This restaurant began to charge for bread that used to be free while you waited for your dinner. This annoyed some customers.

- The Endowment Effect is also why wages don’t really decrease during a recession. Theoretically, wages should fall in a recession because demand for goods and services drops. But wages and salaries typically don’t fall because that would make workers very angry. They are at their current wage (the reference point) and any drop is deemed unfair.

- Instead, companies choose to lay off surplus workers.

- Temporary spikes in demand are a bad time for a business to get greedy.

- Ex. iTunes — iTunes raised the price of Whitney Houston’s albums in the UK after her death in 2012. People were very, very mad.

- Ex. Coca-Cola — Tried to introduce ‘dynamic pricing’ with their vending machines. Warm areas of the country were going to have prices increase at the vending machines. Outrage ensued and the CEO was fired.

- Ex. Uber — The company was hiking rates significantly in New York during periods of crisis, like blizzards and snow storms. People were having to pay crazy prices to get a ride. The state eventually forced Uber to cap its crazy price increases during these times.

- Chapter Takeaway — To produce good, long-lasting partnerships with customers, a business shouldn’t significantly overcharge in periods of high demand, even if the customer is willing to pay a higher market price. When firms do this, customers see right through it and get a bad impression of the company. They don’t come back and they may also leave bad reviews.

Ch. 15: Fairness Games

- Thaler, Kahneman, and others created ‘fairness games’ to investigate how customers behaved when treated unfairly by companies.

- These games presented hypothetical situations to respondents, who had to choose their responses.

- Quote (P. 142): “There is clear evidence that people dislike unfair offers and are willing to take a financial hit to punish those who make them.”

- Chapter Takeaway — People don’t like unfair offers and are willing to sacrifice to punish companies that deploy them.

Ch. 16: Mugs

- 1990 — Thaler and Kahneman publish a paper on The Endowment Effect in which they used a series of experiments involving Cornell coffee mugs to definitively prove that people don’t like to give things up.

- Up to this point, there were many traditional economists who doubted the effect.

- They were of the opinion that people don’t have an emotional attachment to things and would buy and sell items based on how much they value the item from a monetary perspective.

- They were also of the opinion that it doesn’t matter if people are given things to own — they will be willing to give it up if the price is right.

- Up to this point, there were many traditional economists who doubted the effect.

- Mugs Experiment — Thaler and Kahneman used 22 students as subjects; 11 buyers and 11 sellers. Coffee mugs were given out to 11 of the 22 students at random.

- Economic theory predicts that there would be around 11 trades. In other words, about half of the sellers would be willing to sell freely in the open market if presented with a fair price by a buyer.

- Thaler and Kahneman were predicting a far fewer number of trades because they believed in The Endowment Effect, which states that losses hurt twice as much as gains and people don’t like to give things up.

- Because of this effect, Thaler and Kahneman predicted that the sellers would value their mugs at a much higher price than buyers, which would result in a low number of trades.

- The experiment was run 4 different times with the number of trades coming in at 4, 1, 2, and 2, respectively — all far fewer than 11.

- This was a landmark experiment in behavioral economics. It proved definitively that this effect was real.

- Economic theory predicts that there would be around 11 trades. In other words, about half of the sellers would be willing to sell freely in the open market if presented with a fair price by a buyer.

- Quote (P. 154): “The Endowment Effect experiments show that people have a tendency to stick with what they have, at least in part because of loss aversion. Once I have that mug, I think of it as mine. Giving it up would be a loss.”

- Ex. Salary — We will not accept pay decreases, even if they are justified for poor work. We are at a certain salary number and we will refuse to have that number fall.

- Status Quo Bias — People stick to what they have unless there is a good reason to switch.

- Chapter Takeaway — We don’t like to lose things that are already in our possession. This goes for money, items, people, life conditions, salary, and almost anything else you can imagine. We tend to get attached to things. Again, losses are twice as painful as gains are pleasurable. This experiment with mugs proved it.

Ch. 17: The Debate Begins

- 1985 — An economics conference was held at The University of Chicago to discuss traditional economics and behavioral economics.

- Each side had different economists speak and give their take. The idea was to spark discussion and decide if behavioral economics should be taken seriously.

- Neither side ‘won’ but there was a lot of good discussion that moved the needle. It was becoming clear that adding some psychology to economics was an activity worth pursuing.

- Chapter Takeaway — Behavioral economics was becoming prominent during this time. The traditional economists were having a hard time denying it.

Ch. 18: Anomalies

- Model of Scientific Revolutions —Paradigms change only when experts believe there are a large number of anomalies can’t be explained by the current paradigm, or current way of thinking.

- A scientific term that was introduced by Thomas Kuhn in his book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

- Essentially, changes to the status quote of thinking will not occur until there is enough evidence that proves the current way of thinking is wrong.

- Ex. Copernican Revolution — Placed the sun at the center of the solar system and proved that everything revolves around the sun. It replaced Ptolemaic thinking, which believed all the objects in our solar system revolved around Earth. This shift in belief only happened after enough scientists were able to prove it without a doubt in the 16th Century.

- A paradigm shift in the field of economics was slowly developing with the emergence of behavioral economics.

- The Journal of Economic Perspectives gave Thaler a platform to write about the various anomalies occurring in traditional economics.

- Thaler provided a list of anomalies every quarter. These were published in the journal.

- These articles successfully showed the economics profession that there are a lot of facts that don’t line up with traditional models.

- Ex. Finance — There is a weird ‘calendar’ effect present in the stock market. Stocks tend to go up on Fridays and down on Mondays. January is a good month to hold stocks, especially stocks of small companies. And the market is usually a good amount in the days leading up to a holiday.

- Confirmation Bias — We have a tendency to search for confirming rather than disconfirming evidence. Once we believe something, we only seek evidence or information to confirm it, even if they original hypotheses is wrong.

- Ex. Medical — If we believe something is wrong with our body, we scour the Internet looking for information to confirm our thinking.

- Chapter Takeaway — It takes a lot of unexplainable anomalies to change the standard way of thinking in anything, from pop culture to a field of study.

Ch. 19: Forming a Team

- 1992 — Thaler, Kahneman, and a few others assembled a ‘super team’ of economists to help them further explore and develop the field of behavioral economics.

- The group was called the Behavioral Economics Roundtable and was set up via the Russell Sage Foundation.

- 1994 — The Roundtable began hosting an annual behavioral economics summer camp in Berkeley, California. There have been 300 graduates of the camp.

- Some of the top economics students in the country attended this camp. Many have gone on to become leaders in the field.

Ch. 20: Narrow Framing on the Upper East Side

- Narrow Framing — We sometimes treat economic events or transactions individually rather than combining them. Driven by two biases:

- Bold Forecasts — Based on what Kahneman calls the ‘inside view’ and ‘outside view.’ We tend to make bold forecasts on projects when we are working in groups (inside view) and are surrounded by the optimism of the group. When we remove ourselves from the group and think independently (outside view), we develop a more realistic forecast.

- Ex. Deadlines — When we work on a project, we sometimes predict that we can get it done much sooner than what is actually realistic.

- Timid Choices — Based on Kahneman’s ‘loss aversion’ principle. Essentially, managers are loss averse regarding any outcomes that will be attributed to him/her. This means they will generally not take risks or stray away from how things have previously been done because they are concerned about the fallout if it doesn’t work out. This type of environment can lead to a lack of innovation, progress, experimentation, and problem-solving — key ingredients to the long-term success of any company.

- Ex. Medicine — Thaler worked with a large pharmaceutical company with the goal of getting patients to take their pills more regularly. A ‘text reminder’ solution was presented but shot down my management. It would have required a good investment of money to pull off, but management didn’t want to take the risk despite clear benefits.

- Hindsight Bias also factors in here. After a project fails, it’s easy for top-level leadership to forget that they were part of the decision and instead act as if the poor outcome was obvious.

- In most cases, timid choices are made because there is a culture of fear that starts with the leadership of the company. The best environment is one that encourages well-researched risks and doesn’t punish people if the risks don’t pay off.

- Bold Forecasts — Based on what Kahneman calls the ‘inside view’ and ‘outside view.’ We tend to make bold forecasts on projects when we are working in groups (inside view) and are surrounded by the optimism of the group. When we remove ourselves from the group and think independently (outside view), we develop a more realistic forecast.

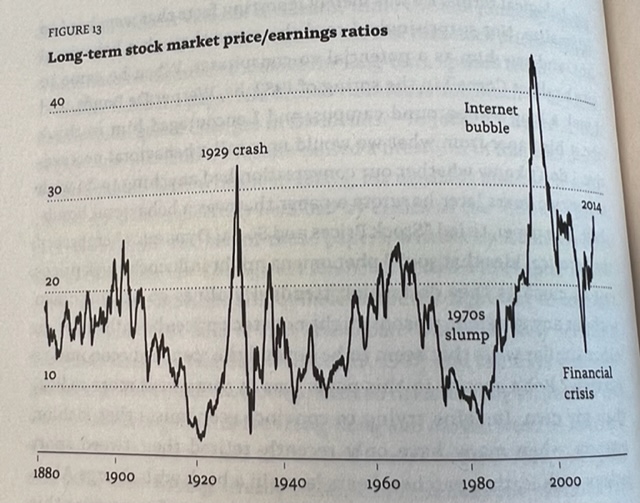

- Equity Premium — Difference in returns between stocks and some risk-free asset, such as short-term government bonds (TBills).

- 1889-1978 — The average risk premium was 6%.

- Stocks are riskier than government bonds, so investors demand a premium for taking on the additional risk.

- Equity Premium Puzzle — Thaler tried to explain why so many people would hold bonds when the expected return on stocks is expected to be 6% or higher.

- Myopic Loss Aversion — When we are loss averse AND evaluate outcomes too much. Thaler found that we sometimes take too much of a short-term view with our investments because we tend to look at our portfolio too often, which scares us out of stocks and steers us towards safer bonds.

- Quote (P. 197): “The more often people look at their portfolios, the less willing they will be to take on risk, because if you look more often, you will see more losses.”

- Quote (P. 198): “These experiments demonstrate that looking at the returns on your portfolio more often can make you less willing to take risk.”

- Ex. Thaler ran an experiment on employees at USC in which he showed two groups the 1-year and 30-year stock charts for a risky stock fund and a safe bond fund. The group that saw the 30-year charts for each fund put 90% of their fake money in stocks. The other group that saw the 1-year charts for each fund put only 41% of their fake money in stocks.

- Over a long time horizon, stocks are clearly the better play despite being a bit riskier in the short term. Over time, repeated risky plays usually go well.

- Ex. In 2010, retirement funds in Israel were forced to report the portfolio returns for the past year when a user first logged in to their account. Prior to this, the first return a user would see was for the past month. This regulatory change immediately led to investors putting more money in stocks.

- Myopic Loss Aversion — When we are loss averse AND evaluate outcomes too much. Thaler found that we sometimes take too much of a short-term view with our investments because we tend to look at our portfolio too often, which scares us out of stocks and steers us towards safer bonds.

- Chapter Takeaway — Risky plays should be commended, even if the results don’t go well. To accelerate progress and innovation, companies should encourage risk-taking and experimentation rather than create a culture of fear that stymies it. In the financial markets, the risks associated with stocks pay nice rewards over the long haul. To avoid our tendency for myopic loss aversion, try not to look at your portfolio very often.

Ch. 21: The Beauty Contest

- The Efficient Market Hypothesis — States that stock market prices move efficiently and reflect all possible public information. It assumes that nobody makes mistakes — and if they do, smart investors capitalize to balance the mistakes out — so all prices are an accurate representation of what the stock is worth. Traditional economists believe in this theory strongly because they assume everyone acts rationally. Introduced in 1970, there are two components:

- Rationality of Prices — Any asset will sell for its true ‘intrinsic value.’ If the rational valuation of a company is $100 million, then all shares will be accurately priced in the market and the company’s market cap (share price x number of shares) will be $100 million on the dot.

- Can’t Beat the Market — Because all publicly available information is reflected in current stock prices, it is impossible to reliably predict future prices and make a profit. Essentially, there’s no point in trying to beat the market.

- The Beauty Contest — Keynes used the analogy of a beauty contest to describe how fund managers pick stocks.

- In the 1930s, people could win a beauty contest by picking the six prettiest faces out of 100. The nature of the competition was that you had to pick the faces that you thought others would pick, not necessarily the ones that you thought were prettiest.

- It’s the same with stocks. You’re trying to buy stocks that you think other people will buy later.

- In the 1930s, people could win a beauty contest by picking the six prettiest faces out of 100. The nature of the competition was that you had to pick the faces that you thought others would pick, not necessarily the ones that you thought were prettiest.

- Quote (P. 215): “Buying a stock that the market does not fully appreciate today is fine, as long as the rest of the market comes around to your point of view sooner rather than later.”

- The stock market is a game of guessing what others are thinking. Everyone is trying to pick stocks that are undervalued. Fund managers are essentially trying to buy the stocks that they believe will be jumped on by the herd.

- Chapter Takeaway — The stock market is not some perfectly efficient machine, although most traditional economists believe that via the Efficient Market Hypotheses. In the end, you’re trying to pick stocks that you believe will be bought up at a later date by other investors. You do this to ride the upward price momentum.

Ch. 22: Does the Stock Market Overreact?

- P/E Ratio — First introduced by Benjamin Graham. The higher a stock’s P/E, the more an investor is paying for every $1 of profit and therefore the more overpriced it is. Low P/E ratios indicate good prices and good value.

- P/E = Market Price / EPS

- EPS = Total Net Income / Shares Outstanding

- It’s a multiple. “The stock is trading at __ times earnings.”

- A high P/E indicates that investors are anticipating good future growth rates and are willing to pay a premium for those anticipated earnings.

- High P/E = Optimism

- A low P/E indicates that investors are down on the stock. If you can find good companies trading at a low P/E ratio, you could have a good deal on your hands.

- Low P/E = Pessimism

- P/E = Market Price / EPS

- Overreaction Hypothesis (1985) — Thaler and his colleagues set out to show that high P/E ratios indicate that investors are overly optimistic and low P/E ratios indicate that investors are overly pessimistic. The goal was to show that investors overreact and there is always a ‘regression to the mean’ in these cases.

- Regression to the Mean — When something unusual happens that can’t be maintained. Future results will come back to normal.

- Ex. Basketball — A player scores 50 points in a game. His next game will likely feature a regression to the mean where he scores something like 15-20 points.

- The Study — Thaler monitored the stocks in the NY Stock Exchange for 3-5 years and picked two separate portfolios of ‘winners’ and ‘losers’. The hypothesis was that the ‘loser’ portfolio would then outperform the ‘winner’ portfolio in the following three year stretch because both groups of stocks would regress to the mean after overreaction by investors.

- Thaler found that this was true. The ‘loser’ portfolio outperformed the ‘winner’ portfolio by a large margin, indicating that investors tend to overreact and push the price of some stocks too high over time.

- The ‘loser’ portfolio also significantly outperformed the market as a whole.

- This finding was important because it was in direct conflict with the EMH, which states that all prices are accurate and nobody can ‘beat’ the market.

- Thaler found that this was true. The ‘loser’ portfolio outperformed the ‘winner’ portfolio by a large margin, indicating that investors tend to overreact and push the price of some stocks too high over time.

- Regression to the Mean — When something unusual happens that can’t be maintained. Future results will come back to normal.

Ch. 23: The Reaction to Overreaction

- Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) — States that the correct measurement of a stock’s risk is its correlation with the rest of the market, which is called Beta.

- Beta — If a stock has a Beta of 2.0, then when the market goes up or down by 10% the stock will on average go up or down by 20%.

- EMH defenders immediately disputed Thaler’s findings from the previous chapter by saying the ‘loser’ stocks were riskier and therefore should outperform.

- But it was the opposite — the ‘winner’ portfolio had a Beta of 1.37 while the ‘loser’ portfolio had a Beta of 1.03, meaning the ‘winner’ portfolio was actually riskier.

- Quote (P. 228): “To this day, there is no evidence that a portfolio of small firms or value firms is observably riskier than a portfolio of large growth stocks.”

Ch. 24: The Price is Not Right

- October 19, 1987 — Black Monday. Stock prices fell 20% in one day for no apparent reason.

- This event was further proof that the EMH was not accurate. The stock market dropped significantly without the occurrence of any big public news.

- 1984 — Robert Schiller of Yale published a paper that showed how stock prices are influenced by social dynamics, much like fashion.

- Quote (P. 233): “Value stocks, either those with very low price/earnings ratios or extreme past losers, predictably outperform the market.”

- This is because stocks with these characteristics regress to the mean. They bounce back. The previous chapter explained this.

- Quote (P. 234): “When the market diverges from its historical trends, eventually it reverts back to the mean.”

- 1970s — Stocks looked cheap and eventually recovered.

- 1990s — Stocks looked expensive and eventually crashed.

- Check the P/E ratio of the S&P 500. If it is especially high or low, a return to the mean is likely coming.

- Quote (P. 236): “When prices diverge strongly from historical levels, in either direction, there is some predictive value in these signals. And the further prices diverge from historic levels, the more seriously the signals should be taken.”

- Regression to the mean will even out a hot or cold spell out.

- Quote (P. 236): “Investors should be wary of pouring money into markets that are showing signs of being overheated, but also should not expect to be able to get rich by successfully timing the market.”

- Do not try to time the market. It’s too difficult to pull off consistently.

Ch. 25: The Battle of Closed-End Funds

- The Law of One Price — In an efficient market, the same asset cannot sell for two different prices. That would create an opportunity for arbitrage, meaning a way to make trades in different markets for a guaranteed profit with no risk. This law was at the heart of the EMH.

- Closed-End Fund — Type of mutual fund that issues a fixed number of shares through a single initial public offering (IPO) to raise capital for its initial investments. Its shares can then be bought and sold on a stock exchange but no new shares will be created and no new money will flow into the fund.

- Thaler wrote a paper showing how the Net Asset Value (total assets – total liabilities) of closed-end funds often differs from the fund’s share price in the market, creating two different prices. The fund’s shares will often trade at a premium or discount to the fund’s NAV.

- If the EMH Law of One Price was accurate, this would never happen. This was another big blow to the EMH.

- Thaler wrote a paper showing how the Net Asset Value (total assets – total liabilities) of closed-end funds often differs from the fund’s share price in the market, creating two different prices. The fund’s shares will often trade at a premium or discount to the fund’s NAV.

- Closed-End Fund — Type of mutual fund that issues a fixed number of shares through a single initial public offering (IPO) to raise capital for its initial investments. Its shares can then be bought and sold on a stock exchange but no new shares will be created and no new money will flow into the fund.

Ch. 26: Fruit Flies, Icebergs, and Negative Stock Prices

- There are examples of past discrepancies in the market that have contradicted the EMH.

- 3Com and Palm — A technology company called 3Com decided to break apart from one of its departments, Palm.

- Surprisingly, shares of Palm increased in price significantly while shares of 3Com dropped.

- 3Com and Palm — A technology company called 3Com decided to break apart from one of its departments, Palm.

Ch. 27: Law Schooling

- The Coase Theorem — In the absence of transaction costs, meaning that people can easily trade with one another, resources will flow to their highest valued use.

- A Behavioral Approach to Law and Economics — In this paper, Thaler and his colleagues proved the Coase Theorem wasn’t always right with their coffee mugs experiment (discussed earlier). The Coase Theorem predicts that half the mugs would be traded so the students who liked the mugs the most would get them. In the experiment, however, the trade volume was much lower because of the Endowment Effect.

Ch. 28: The Offices

- 2002 — The University of Chicago Booth School of Business had a ‘draft’ for offices. The department was preparing to open a new building in 2003.

Ch. 29: Football 🏈

- The NFL Draft — Thaler took a deep look at the history of the NFL Draft to investigate how organizations choose employees. Thaler’s hypothesis was that teams overvalue the right to pick early in the first round. This hypothesis was supported by five findings from the psychology of decision-making:

- People are Overconfident — People are likely to think their ability to evaluate the differences between two players is better than what it really is.

- Extreme Forecasting — Scouts and management too often predict that a player is going to be a superstar.

- The Winner’s Curse — When many bidders compete for the same object, the winner of the auction is often the bidder who most overvalues the object being sold. Usually, the winner overvalues the player.

- The False Consensus Effect — People tend to think that others share their preferences and thoughts. We project our thoughts onto others and assume they are thinking what we’re thinking. In the NFL Draft, when a team likes a player, they assume that every other team likes that player as much as they do. This can lead to desperation and teams can sometimes make unnecessary trades.

- Present Bias — Teams want to win now. When they feel like they are one player away from turning their fortunes around or becoming a Super Bowl contender, they can get desperate and overvalue early round picks.

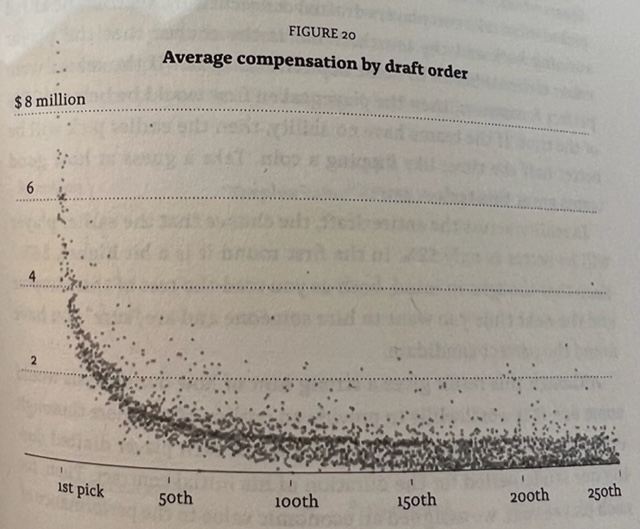

- Thaler found that high first round draft picks are really expensive in two ways:

- Picks — It costs A LOT to trade up and acquire a Top-5 pick.

- Ex. 2012 — Washington traded St. Louis its No. 6 pick to acquire the No. 2 pick. Washington also gave up its first and second round picks in the 2013 draft AND its first-round pick in the 2014 draft. All of this was in order to draft QB Robert Griffen III with the No. 2 pick.

- Money — A player selected in the Top-5 is paid a lot more than players selected later in the draft. The drop off is extreme. See chart:

- Picks — It costs A LOT to trade up and acquire a Top-5 pick.

- The question Thaler set out to answer was: Are these high draft picks worth it? The answer is: Usually not. It sort of depends on how good the teams are at evaluating talent.

- Quote (P. 284): “In reality, across the entire draft, the chance that the earlier player will be better is only 52%. In the first round it is a bit higher, 56%. Keep that thought in mind the next time you want to hire somebody and are ‘sure’ you have found the perfect candidate.”

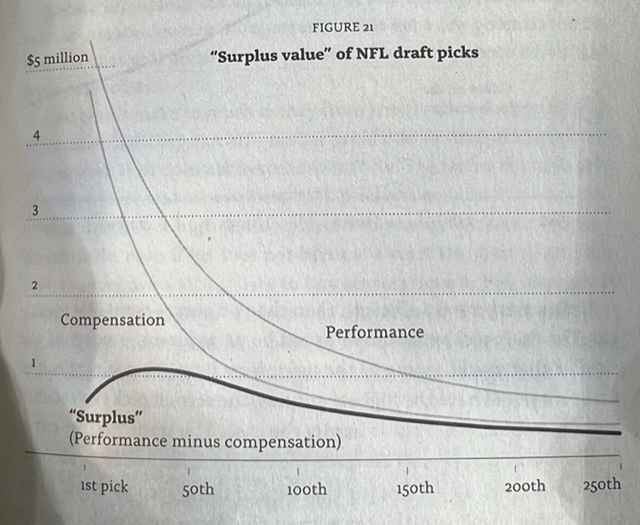

- Surplus Value — Thaler found a player’s surplus value to the team by subtracting the player’s compensation by the player’s performance value.

- He found that early round draft picks actually have negative surplus value compared to players picked later in the draft. Essentially, early picks are worth less than later picks.

- Ex. You can get more overall value by trading a high pick for several second-round picks.

- See Surplus Value chart:

- He found that early round draft picks actually have negative surplus value compared to players picked later in the draft. Essentially, early picks are worth less than later picks.

Ch. 30: Game Shows

- The Matthew Effect — Excessive credit for any idea will be attributed to the most well-recognized person associated with it.

- Path Dependence — Thaler and colleagues used the Dutch game show Deal or No Deal to confirm the validity of path dependence, which states that past events or decisions dictate future events or decisions.

- Traditional economic theories suggest that path dependence isn’t real. Every decision should be made based on the circumstances right in front of you in a vacuum. How a situation has developed up to that point should not matter.

- In Deal or No Deal, contestants on the show routinely made decisions based on how the game had developed to that point. This was exemplified via the game in two ways that Thaler had already wrote about years prior (discussed in previous chapters):

- The House Money Effect — When contestants were doing well in the game, they were likely to take more chances because they felt like they were playing with ‘house money.’ If they lost the money, no big deal. It wasn’t they’re money anyway. That’s the mindset with this effect.

- Break-Even Effect — When contestants were winning big and suddenly suffered a big blow in the game, many exhibited a tendency to try to get it all back by taking big risks.

- Big Peanuts Hypothesis — The idea that a certain amount of money can appear small or large depending on context.

- Ex. When offered a chance to save $10 on a $60 product by running across town to a different store, respondents were more likely to do it than if they were offered the same $10 off for a $250 product if they ran across town to a different store.

- Ex. In Deal or No Deal, a contestant named Frank started out hot and had a deal from the baker of $400,000 Euros. He turned it down and kept losing. At the very end of his run, he was offered $20,000 Euros from the baker and he chose to keep the suitcase he picked at the start of the show, which revealed $10 Euros. The hypothesis here is that Frank felt like he was offered a very small amount ($20,000 Euros) at the end compared to the $400,000 Euros he was offered earlier in the game and so decided to take an unnecessary risk by opting for his suitcase instead of taking the $20,000 Euros.

Ch. 31: Save More Tomorrow

- Retirement Problems — Around the world, people don’t save enough for retirement. Thaler identified three behavioral reasons for this in a presentation he gave to Fidelity on the late 1990s.

- Inertia — Surveys reveal that people plan to save more for retirement, but never get around to it. They procrastinate. The idea of filling out paperwork and sifting through information they don’t fully understand leads to inaction.

- Takeaway — You have to make it easy for people to sign up for and/or do something, otherwise they usually won’t do it. This lesson can be applied to all areas of life.

- Loss Aversion — As discussed earlier, we don’t like to lose things. We definitely don’t like to see our paycheck decrease, even if it’s due to saving for retirement.

- Self-Control — We have more self-control when it comes to the future than the present.

- Inertia — Surveys reveal that people plan to save more for retirement, but never get around to it. They procrastinate. The idea of filling out paperwork and sifting through information they don’t fully understand leads to inaction.

- Save More Program — An automatic enrollment plan designed by Thaler to negate these three behavioral issues and help people save more for retirement. Key features:

- Automatic Enrollment — Rather than having people have to sign up for the retirement plan, select a savings rate, and select investment options, automatic enrollment throws them into these things and they have to opt out to get out of the plan. In this way you’re making inertia work for you — it now takes effort to get out of the plan.

- Savings Rate Increases — If agreed upon, the employee would automatically increase his savings rate with each raise acquired. By tying increases in saving rate with increases in pay, the loss aversion component is negated.

- The Power of Suggestion (1999) — Paper written by Bridgette Martian that discussed the success of automatic enrollment retirement plans.

- Before automatic enrollment, only 49% of employees joined the plan during the first year of eligibility; after automatic enrollment, that number jumped to 86%. Only 14% opted out.

- Again, automatic enrollment is successful because it takes the effort out of the employee’s hands. Instead, it takes effort to opt out of the plan.

- By 2011, 56% of employers were using these automatic enrollment plans.

- Before automatic enrollment, only 49% of employees joined the plan during the first year of eligibility; after automatic enrollment, that number jumped to 86%. Only 14% opted out.

- Quote (P. 319): “A key lesson we learned, which confirmed a strongly held suspicion, was that participation rates depended strongly on the ease with which employees could learn about the program and sign up. Brian‘s set up for this was ideal. He showed each employee how dire his savings situation was, offered him an easy plan for starting down a better path, and then helped him fill out and return the necessary forms.”

- This is an important lesson, especially in the field of marketing. Many people will not put in the effort to sign up for something unless you make it very easy and convenient for them. You’re fighting against human nature.

Ch. 32: Going Public

- Nudge — A 2008 book written by Thaler and Cass Sunstein. The premise of the book was about how we can use libertarian paternalism in public policy to help ‘nudge’ people to make good decisions for themselves.

- People make predictable errors. If we can anticipate those errors, we can create policies that will help reduce the error rate.

- Paternalism — Trying to help people achieve their own goals.

- Nudge — Some small feature in the environment that attracts our attention and influences our behavior.

- Ex. Highway Bumps — Along the side of many of our highways are deep grooves/bumps in the road that are designed to make a ton of noise when driven on. These are in place to wake a driver up if they doze off and drift off the road.

- Ex. Natural Disasters — John Tierney of the New York Times had an idea of giving anybody that wanted to stay in town when a hurricane was approaching a permanent marker so they could mark their bodies with their social security number. That way, rescuers would be able to identify their body after the hurricane swept through town. This was designed to ‘nudge’ people to leave and approach higher ground.

- Default Options — Similar to automatic enrollment. When people are put inside something by default, they rarely take the steps necessary and make the proper effort to opt out.

- Ex. Organ Donors — In many countries, people are identified as organ donors by default. They have to actively opt-out in order to not be an organ donor. In these countries, the opt-out rate is extremely low. In countries where you have to opt-in to be an organ donor, the opt-in rates are very low.

- Takeaway — We are all very lazy and don’t act.

- Ex. Organ Donors — In many countries, people are identified as organ donors by default. They have to actively opt-out in order to not be an organ donor. In these countries, the opt-out rate is extremely low. In countries where you have to opt-in to be an organ donor, the opt-in rates are very low.

Ch. 33: Nudging in the UK

- 2009 — Thaler joins the ‘Behavioral Insights Team’ (BIT) with the United Kingdom government. This team advised David Cameron, who later became the Prime Minister in 2010.

- The team’s goal was simply to use the insights from behavioral science to improve the workings of the government.

- Her Majesty’s Revenues and Customs (HMRC) — This was the first group the BIT worked with. This department was responsible for collecting tax payments from citizens in the UK. The department was having trouble collecting from people and were looking for a solution.

- The Letter — If a person misses the deadline to send in their tax payment, the HMRC sends a letter asking for payment. The BIT helped the HMRC reshape that letter with a nudge. The nudge was based on the Dr. Robert Cialdini bible — If you want people to comply with some norm or rule, it is a good strategy to inform them (if true) that most other people comply.

- The Nudge — The letter was adjusted to include a statement that essentially stated that most people pay their taxes and the person receiving the letter was one of the few who hasn’t.

- Results — Over the next 23 days, the number of taxpayers who made their payments increased by 5%, which amounted to over $9 million in revenue to the British government.

- The Nudge — The letter was adjusted to include a statement that essentially stated that most people pay their taxes and the person receiving the letter was one of the few who hasn’t.

- The Letter — If a person misses the deadline to send in their tax payment, the HMRC sends a letter asking for payment. The BIT helped the HMRC reshape that letter with a nudge. The nudge was based on the Dr. Robert Cialdini bible — If you want people to comply with some norm or rule, it is a good strategy to inform them (if true) that most other people comply.

- Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) — The BIT worked with the DECC to develop a nudge designed to get people to insulate their attics. Too many people in the UK had not insulated their attics, citing “too much clutter” in their attics. Essentially, they didn’t insulate their attic because they didn’t want to clean it out.

- The Nudge — The BIT helped the DECC offer a bundled service where the people installing the insulation would also help the person clean out the attic for an additional cost.

- The Results — Nearly every family that chose to insulate their attics after this nudge was assembled selected one of the bundled options, indicating that the package deals were a successful in changing behavior. By helping them clean their attic, they were more likely to insulate their attic.

- The Nudge — The BIT helped the DECC offer a bundled service where the people installing the insulation would also help the person clean out the attic for an additional cost.

- Quote (P. 342): “Those looking for behavioral interventions that have a high probability of working should seek out other environments in which a one-time action can accomplish the job.”

- Again, you have to make it easy for people. Whenever you want someone to do something, you have to find ways to make it as easy as possible.

- Texting Nudge — Text reminders have proven to be very effective nudges.

- Ex. Medication — In Ghana, text reminders have been extremely effective in getting people to take their malaria medication.

- Ex. Education — A program named READY4K! sends parents daily text reminders containing tips for good parenting, including ways to help kids read and write. A study that evaluates the program found that the texts have led to “significant increases in parental involvement in literacy activities.”

- Ex. Education — At one school in the UK, half of the parents were sent text reminders that their child had a test coming up. A study that monitored the text program showed that the kids whose parents received the texts performed much better than the kids whose parents did not receive the texts.