Leonardo da Vinci

Walter Isaacson

GENRE: Biographies & Memoirs

GENRE: Biographies & Memoirs

PAGES: 624

PAGES: 624

COMPLETED: December 21, 2024

COMPLETED: December 21, 2024

RATING:

RATING:

Short Summary

Whether he was painting The Mona Lisa, dissecting a body, or trying to “describe the tongue of a woodpecker,” Leonardo da Vinci’s talent and curiosity knew no bounds. Walter Isaacson captures it all in this biography of one of history’s most fascinating people.

Key Takeaways

Favorite Quote

“He [Leonardo] was not graced with the type of brilliance that is completely unfathomable to us. Instead, he was self-taught and willed his way to his genius. So even though we may never be able to match his talents, we can learn from him and try to be more like him. His life offers a wealth of lessons.”

Introduction

- About the Book — This is a biography of Leonardo da Vinci, one of the great artists and scientists in history. As this book describes, Leonardo was a jack of all trades — he was a skilled artist, engineer, scientist, and inventor. His ability to excel in multiple different disciplines made him brilliant. To write this book, Walter Isaacson drew on more than 7,200 pages of notes left behind by Leonardo, along with scores of other literary works authored by historians around the globe. Many of Leonardo’s personal notes contained sketches and drawings that he later turned into full-blown masterpieces, like the world-famous Mona Lisa and The Last Supper.

- About the Author — Walter Isaacson is a renowned author who has written biographies on Albert Einstein, Steve Jobs, Benjamin Franklin, Elon Musk, and more. He has served as a professor of history at Tulane University, CEO of the Aspen Institute, chairman of CNN, and editor of Time magazine.

- Jack of All Trades & Captain Curiosity — Leonardo was a man of many talents, excelling in art, science, engineering, and more. What made him such a jack of all trades was his relentless thirst for knowledge. He is described as obsessively and oddly curious, always looking for new things to learn. He’s considered a genius but not because he was gifted unordinary skills and abilities. Rather, his relentlessly curious mind kept him pushing to learn and grow. The knowledge and skills he developed out of sheer will and dislike helped him accomplish great things in his life. For example, in his notebook he wrote reminders for himself to learn how to repair locks, canals, and mills, and to “describe the tongue of a woodpecker.”

- Quote (P. 1): “But in his own mind, he was just as much a man of science and engineering. With a passion that was both playful and obsessive, he pursued innovative studies of anatomy, fossils, birds, the heart, flying machines, optics, botany, geology, water flows, and weaponry.”

- Quote (P. 2): “Together they served his driving passion, which was nothing less than knowing everything there was to know about the world, including how we fit into it.”

- Quote (P. 3): “Yes, he [Leonardo] was a genius: wildly imaginative, passionately curious, and creative across multiple disciplines. But we should be wary of that word. . . Leonardo’s genius was a human one, wrought by his own will and ambition. It did not come from being the divine recipient, like Newton or Einstein, of a mind with so much processing power that we mere mortals cannot fathom it. Leonardo had almost no schooling and could barely read Latin or do long division. His genius was of the type we can understand, even take lessons from. It was based on skills we can aspire to improve in ourselves, such as curiosity and intense observation.”

- Quote (P. 5): “His notebooks are the greatest record of curiosity ever created, a wondrous guide to the person whom the eminent art historian Kenneth Clark called ‘the most relentlessly curious man in history’.”

- Chapter Takeaway — Leonardo was an extremely curious guy who was always pushing himself to learn and grow. Although he is known for his brilliant artwork, he was also a skilled scientist and engineer. His passion for learning helped him become great at many things.

Ch. 1: Childhood

- A Star Is Born — Leonardo was born April 15, 1452 in the small town of Vinci, about 17 miles from Florence, Italy. His name literally translates to “Leonardo from Vinci.” His father, Piero, was a successful notary. His mother, Caterina, was an impoverished 16-year-old from the Vinci area. The two had a fling in 1451, and Leonardo was born out of wedlock the next year. As a result, Leonardo split his childhood between two homes: Caterina lived on the outskirts of Vinci, while Piero resided in Florence. But by age five, Leonardo was primarily living with the da Vinci family home with his grandpa, Antonio. The da Vinci family had better opportunities for education and stability than Caterina’s situation.

Ch. 2: Apprentice

- Move to Florence — In 1464, at age 12, Leonardo moved to Florence to join his dad. Florence in the 1400s was one of the most beautiful and stimulating environments in the world. Its economy grew tremendously during this time period as art, technology, and commerce flourished. Creativity was everywhere. It was here that a young Leonardo took an apprenticeship and began to find his stride.

- Mirror Writing — Leonardo was a left-hander and became so annoyed by smearing the ink as he wrote from left to right that he taught himself to write and draw from right to left on a page. Each letter he wrote was facing backward. A friend of his called this “mirror writing.”

- Apprenticeship — At age 14, Leonardo took on an apprenticeship under Andrea del Verrochio, a versatile artist and engineer who operated one of the best workshops in Florence. The apprenticeship was the perfect launching pad for a young Leonardo. He held this apprenticeship until 1472, when he was age 20. Even after completing it, he stayed with the workshop for a number of years because he enjoyed the culture so much. Verrochio turned out to be a terrific mentor and friend for Leonardo as he discovered and honed his skills.

- Apprenticeship: What He Learned — During his years as an apprentice, Leonardo learned how to use light, shade, and shadows to make paintings look three dimensional, leverage basic geometry to create art, and manufacture the appearance of movement/motion in his paintings. The first — effectively using shading techniques to make parts of his paintings pop off the page and appear three dimensional — became one of his signatures as an artist. He also learned how to blur the edges of his shapes in order to create undefined features. This blurring technique, known as sfumato, had never been used before and became another Leonardo signature. In fact, most artists at the time purposely created very defined lines in their work. He used these techniques in nearly all of his paintings, including the Mona Lisa.

- Quote (P. 41): “The term sfumato derives from the Italian word for ‘smoke’, or more precisely the dissipation and gradual vanishing of smoke into the air. ‘Your shadows and lights should be blended without lines or borders in the manner of smoke losing itself in the air’, he wrote in a series of maxims for young painters. From the eyes of his angel in the Baptism of Christ to the smile of the Mona Lisa, the blurred and smoke-veiled edges allow a role for our own imagination.”

- Chapter Takeaway — Leonardo’s career began in the workshop of Andrea del Verrochio in Florence, where he was an apprentice and learned some of his signature moves while contributing to various paintings. Florence in the 1400s was one of the best places to be for creative thinkers and artists.

Ch. 3: On His Own

- Homosexuality — Leonardo was gay. Being homosexual wasn’t uncommon in Florence in the 1400s, but it was considered a sin by the church, and Leonardo was sometimes investigated for alleged sexual acts with other men. Unlike other great artists of that time period who were also gay, like Michelangelo, Leonardo didn’t seem bothered by his sexual tendencies. In many ways, he channeled into his work that feeling of being an outsider.

- Starting His Own Shop — Leonardo continued working at Andrea del Verrochio’s workshop for several years after his apprenticeship ended. But in 1477, he finally ventured out and started his own shop. Commercially, it was a failure. In the following five years, he received only three jobs — two of which he started and didn’t complete, and one of which he never started. Nevertheless, the two pieces of art he started but didn’t finish showed so much promise that they actually enhanced his reputation significantly. One of these was The Adoration of the Magi, considered “the most influential unfinished painting in the history of art.” Leonardo started this piece in 1481 at age 29.

- Chapter Takeaway — At age 30, Leonardo didn’t have a lot to show for his career. He completed his apprenticeship and later started his own shop, but he was still relatively unknown. The signs of brilliance were there, but he didn’t yet have any major successes under his belt. Sending the need for a change of scenery, he left Florence for Milan.

Ch. 4: Milan

- Leaving For Milan — In 1482, the year he turned 30, Leonardo left Florence for Milan, where he would spend the next 17 years of his life. Milan, with 125,000 citizens at the time, was about three times the size of Florence. Unlike Florence, Milan wasn’t crowded with master artists. This allowed Leonardo’s creative brilliance to stand out more than it was in Florence.

- The Job Application — Not long after he arrived in Milan, Leonardo wrote a long letter to Ludovico Sforza, who was also age 30 and basically ruled Milan at the time. Although not technically the Duke of Milan yet, Sforza was controlling and manipulating the real Duke, his nephew, and later officially took the role in 1494. In his letter to Sforza, Leonardo essentially asked for a job. His letter described his skills in engineering and military innovations before even mentioning his art talent. This was a strategic move, as Milan was a hub for military and political activity. It worked. Leonardo eventually was hired to work for Sforza.

- Great Vision — Although Leonardo liked to fantasize about architectural designs and military innovations, very few of them actually came to fruition. He drew in his notebooks mockups for extravagant crossbows, chariots, tanks, city layouts, and more, but most of these visions were simply ahead of his time and were not possible to execute. These designs were too ambitious for the time being was living in, which is a testament to his imagination and understanding of science and engineering. But his practical impact in these fields was minimal compared to the extraordinary contributions he made to the world of art.

- Chapter Takeaway — Leonardo was a visionary with an unbelievably creative mind. Many of the architectural and military-focused designs he drew in his notebooks were so advanced that they were impossible to execute during the time period he was living in. This is partly why his overall legacy is in art; a field where he had the resources and talent to execute most of his innovative visions.

Ch. 5: Leonardo's Notebooks

- Note-Taking Machine — In the early 1480s, not long after arriving in Milan, Leonardo began keeping detailed notebooks. These notebooks were packed with to-do lists, ideas, sketches, observations, random notes, and so much more. What’s interesting about his notes is that (i.) they contain his mirror writing, and (ii.) many of his pages contain notes on completely separate, unrelated topics. Early on, his notes were mostly centered around ideas that he considered useful for his art and engineering. As he became more interested in science, his notebooks began to include information on things like flight, water, anatomy, art, horses, mechanics, and geology. He was clearly an extremely curious person and wanted to know how and why things worked. The only thing missing from his notebooks are notes about his personal life. These notebooks seem to have been used exclusively for learning and growing.

- Quote (P. 106): “But in their content, Leonardo’s [notebooks] were like nothing the world had ever, or has ever, seen. His notebooks have been rightly called ‘the most astonishing testament to the powers of human observation and imagination ever set down on paper.’”

- Compiling Into Codices — All in all, we have compiled about 7,200 pages of Leonardo’s notebooks, but many historians believe that’s only about 25% of what he actually wrote. After his death, many of his notebooks were disassembled and the interesting pages were sold or reorganized into new “codices” by various collectors. For example, the Codex of Atlanticus consists of 2,238 pages from Leonardo’s notebooks and is held at Milan’s Biblioteca Ambrosiana. The Codex Arundel is held at the British Library and contains 570 pages of Leonardo’s writings assembled by an unknown collector in the 17th century. The Codex Leicester contains 72 pages of Leonardo’s notebooks focused on geology and water studies. This one was bought by Bill Gates in 1994 for $30M. Overall, there are 25 da Vinci codices held at places around the world.

- Chapter Takeaway — Leonardo was one of the most curious people who ever lived, always looking to learn and grow. One of the ways he kept track of everything he was learning was through his notebooks. His notebooks contained information on almost every topic except himself; he wrote down very few observations about his personal life. In the centuries since his death, collectors have packaged his notes on various topics into “codices” that are now held at places around the world.

Ch. 6: Court Entertainer

- Leonardo the Entertainer — In addition to dabbling in military engineering and architecture as outlined in the chapter above, Leonardo also enjoyed producing pageants, events, and shows for the Sforza court. When it came to leading these festivities, he worked on stage designs, costumes, scenery, music, choreography, and more — all of which he enjoyed. Just as we love halftime shows, concerts, and Broadway extravaganzas today, people in the 1400s enjoyed their shows and pageants, so Leonardo’s work in this area helped him gain notoriety and respect in Milan and in the Sforza court. Although his contributions here were nice, they aren’t what he is mostly remembered for today.

Ch. 7: Personal Life

- A Good Guy — Leonardo was known as a nice, smart, friendly guy who was kind to everyone he encountered. Unlike some troubled artists of the time period, like Michelangelo, Leonardo was social and very outgoing. He also had a deep love of animals and chose to be a vegetarian for most of his life. He had a lot of friends and often went out of his way to support them with clothes and shelter.

- Companion Salai — Leonardo had quite a few “companions” throughout his life, none more notable than Gian Giacomo Caprotti, who he called “Salai.” At age 10, Salai arrived in Milan in July 1490, when Leonardo was 38. Salai was essentially an assistant and lived with Leonardo. The two had a very close relationship, one that likely turned sexual at some point. Leonardo had an odd fascination with Salai for most his life and enjoyed drawing him in his notebooks.

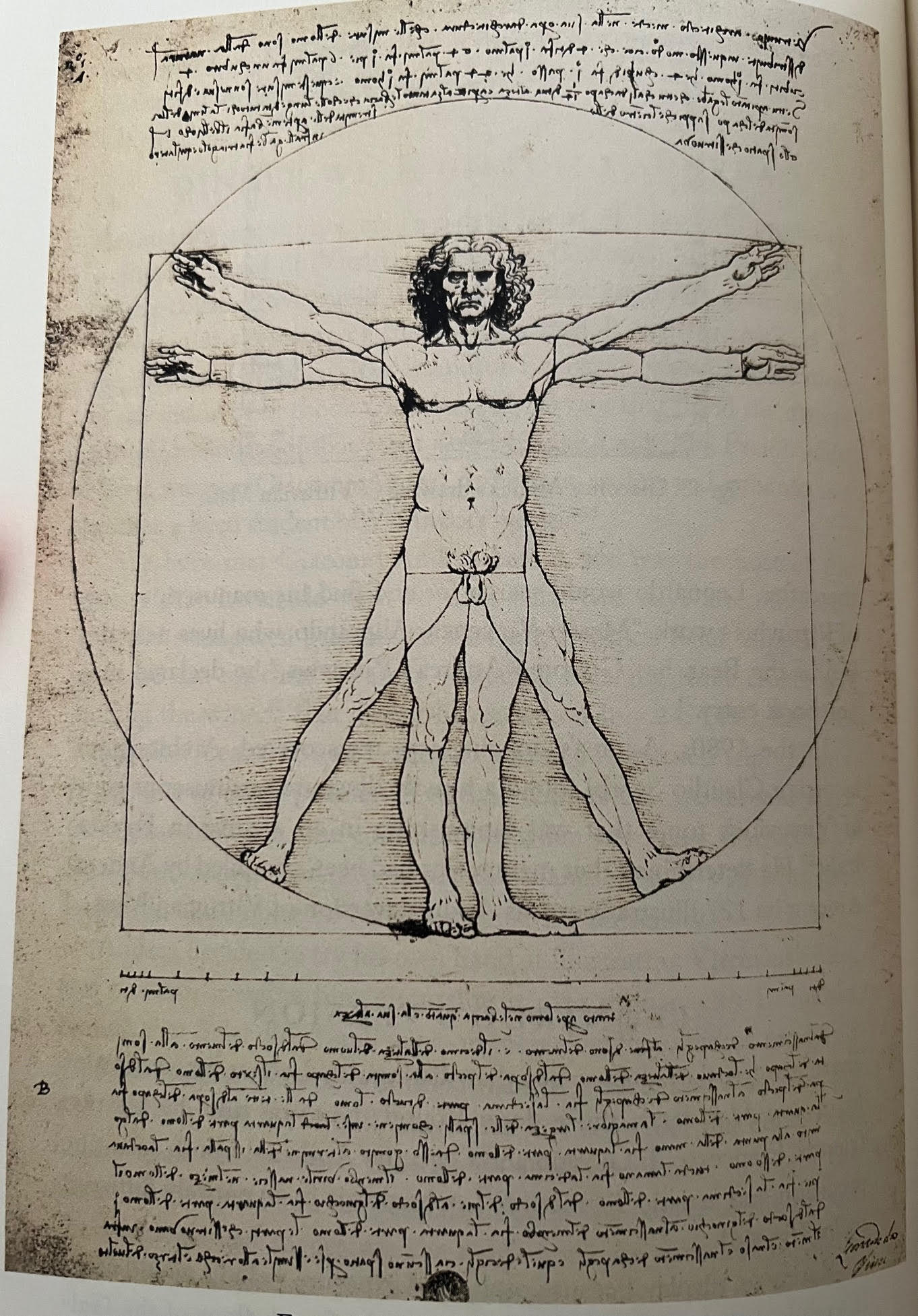

Ch. 8: Vitruvian Man

- Creating Vitruvian Man: Part 1 — Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man is one of the most famous drawings in history. It was inspired by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, an architect who served in the Roman army under Julius Caesar in 80 BC. Vitruvius, as he is known, designed artillery machines for the Roman army and created a 10-volume book on architecture called De Architecura. In this book, Vitruvius discussed the relationship between the microcosm of man and the macrocosm of the earth. He believed the world’s rules for harmony are derived from the human body. Vitruvius applied this analogy to the design of temples — he believed the human body should serve as a model for designing buildings, as if the body were laid out flat on its back on top of the floor plan. Doing so would help the architect achieve harmony and balance in the structure. This concept inspired later architects, including Leonardo, to visualize the idea by “putting a man in a circle and square,” as Isaacson describes.

- Creating Vitruvian Man: Part 2 — Around 1490, at age 38, Leonardo and his friends began studying Vitruvius and trying to draw a man inside of a squared circle. Curiously, Vitruvius never tried this himself. A few architects tried to draw this concept, but most of them didn’t get it quite right. Leonardo’s version is considered the best because of its scientific accuracy and artistic elegance. The proportions of the human body are perfect, and the man is perfectly aligned inside the square and circle, creating harmony and balance. Others who attempted this drawing were not able to achieve the same scientific and artistic precision.

- Creating Vitruvian Man: Part 3 — Vitruvian Man is simple in appearance but has a deep meaning: the circle represents the cosmos and eternity, while the square represents the physical world and human existence. By placing the human figure at the intersection of these shapes, Leonardo suggests that humanity is the link between the earthly and the divine — a central figure in the balance of the universe. Today, the original drawing is rarely on display because prolonged exposure to light would cause it to fade. It is locked up in a room on the fourth floor of the Galerie dell’Accademia in Venice and is only displayed on special occasions.

Ch. 9: The Horse Monument

- The Horse That Never Lived — In 1489, Leonardo was asked by Sforza to design and build a monument glorifying his father, the former Duke of Milan. Leonardo decided on an equestrian statue with the Duke sitting on top of a giant horse. The statue was to be 23-feet high. In preparation, Leonardo became obsessed with studying the anatomy of horses and making precise measurements for each body part. He even dissected horses to learn more about them. Leonardo succeeded in building a full-size clay model in 1493, but in 1494 the project was completely abandoned after the French invaded Italy, eventually conquering Milan in 1499. The bronze that was supposed to be used for the statue was instead used to make cannons to fight the French.

Ch. 10: Scientist

- Heavy Reader — Leonardo was an avid reader and learned much of what he knew through books and asking questions of experts. This helped make up for a lack of formal education. As mentioned toward the beginning of this book, he was an extremely curious guy. His reading included wide-ranging topics such as physics, music, health, architecture, and more. He wanted to know how the world worked, and books were one of the ways he sought knowledge.

- Quote (P. 172): “By 1492 Leonardo had close to forty volumes. A testament to his universal interests, they included books on military machinery, agriculture, music, surgery, health, Aristotelian science, Arabian physics, palmistry, and the lives of famous philosophers, as well as the poetry of Ovid and Petrarch, the fables of Aesop, some collections of bawdy doggerels and burlesques, and a fourteenth-century operetta from which he drew part of his bestiary. By 1504 he would be able to list seventy more books, including forty works of science, close to fifty of poetry and literature, ten on art and architecture, eight on religion, and three on math.”

- Quote (P. 173): “His [Leonardo] appetite for soaking up information from books was voracious and wide-ranging.”

- Curious Cat — Building on the point above, Leonardo was an extremely curious guy. He wanted to know how everything works, from how the tongue of a woodpecker functions and why the sky is blue to which nerve causes the eye to move so the motion of one eye moves the other. Leonardo’s notebooks were filled with reminders to learn certain things. We’d all be wise to mirror that approach. Read books. Ask questions. Always try to understand the world around you. Learning and the pursuit of knowledge is a great thing.

- Quote (P. 179): That’s important, because it means that we can, if we wish, not just marvel at him [Leonardo] but try to learn from him by pushing ourselves to look at things more curiously and intensely.”

Ch. 11: Birds and Flight

- Obsession With Flight — Leonardo was obsessed with flight. His notebooks are filled with words and drawings of birds and flying machines. His interest in flying machines began with his work on theatrical pageants that were popular in Italy at the time. One of the ways he sought to understand the mechanics of flight was through bird-watching. He eventually drew hundreds of designs and attempted to build winged-contraptions and gliders for the purpose of human flight. None of these worked, but he spent a lot of time trying. He was just completely fascinated with flight.

- How Birds Fly — Leonardo’s close observation of birds led him to notice that their wings have a unique shape: the tops are curved while the undersides are relatively flat. This design helps generate lift, which is the force that allows birds to stay aloft. As air flows over the curved top of the wing, it has to move faster, creating an area of lower pressure. Meanwhile, the air moving beneath the flatter underside flows more slowly since it doesn’t have a curve to contend with and therefore exerts greater pressure. The difference in pressure between the top and bottom of the wing lifts the bird into the air. Airplanes use a similar principle: their wings are designed with a curved top and flatter underside to create the same pressure differential, helping them stay in flight. However, birds have an advantage: their wings are flexible and can adjust in shape and angle during flight, allowing for incredible agility and efficiency.

Ch. 12: The Mechanical Arts

- Mechanical Visionary — At this point, it’s clear that Leonardo had a lot of interests. Another one of them was his fascination with engineering and invention. Leonardo was inspired by the parallels between art and mechanics. He designed a variety of innovative devices during his lifetime, including flying machines and hydraulic pumps. As he sought to understand mechanics, he often drew his ideas on paper in an attempt to make them practical. His sketches reveal a visionary understanding of mechanics, though many of his inventions remained conceptual due to technological limitations of his time. His studies in this area complemented his art, allowing him to apply principles of motion and physics to his paintings. Overall, he was a genius for his ability to blend art, science, and engineering in unprecedented ways.

Ch. 13: Math

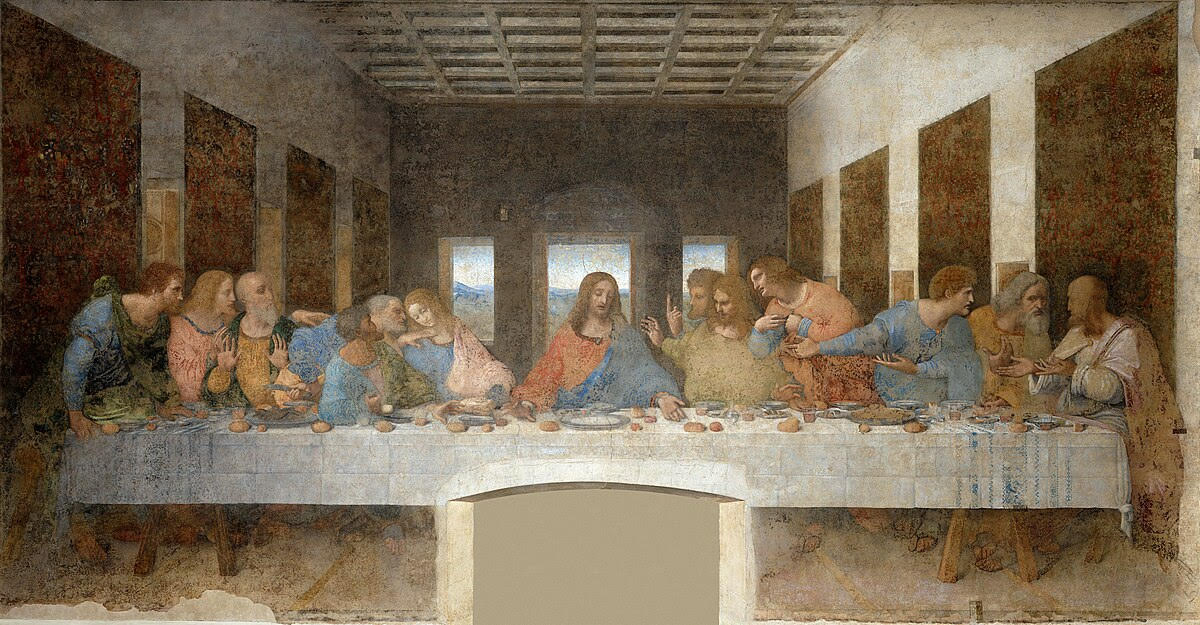

- Mathematician — Leonardo’s fascination with math made him a better artist. He studied geometry, ratios, and proportions, and integrated mathematical concepts into his creative process. He also intentionally applied math to his art, as seen in works like The Last Supper, where he used perspective and ratios to create depth and balance.

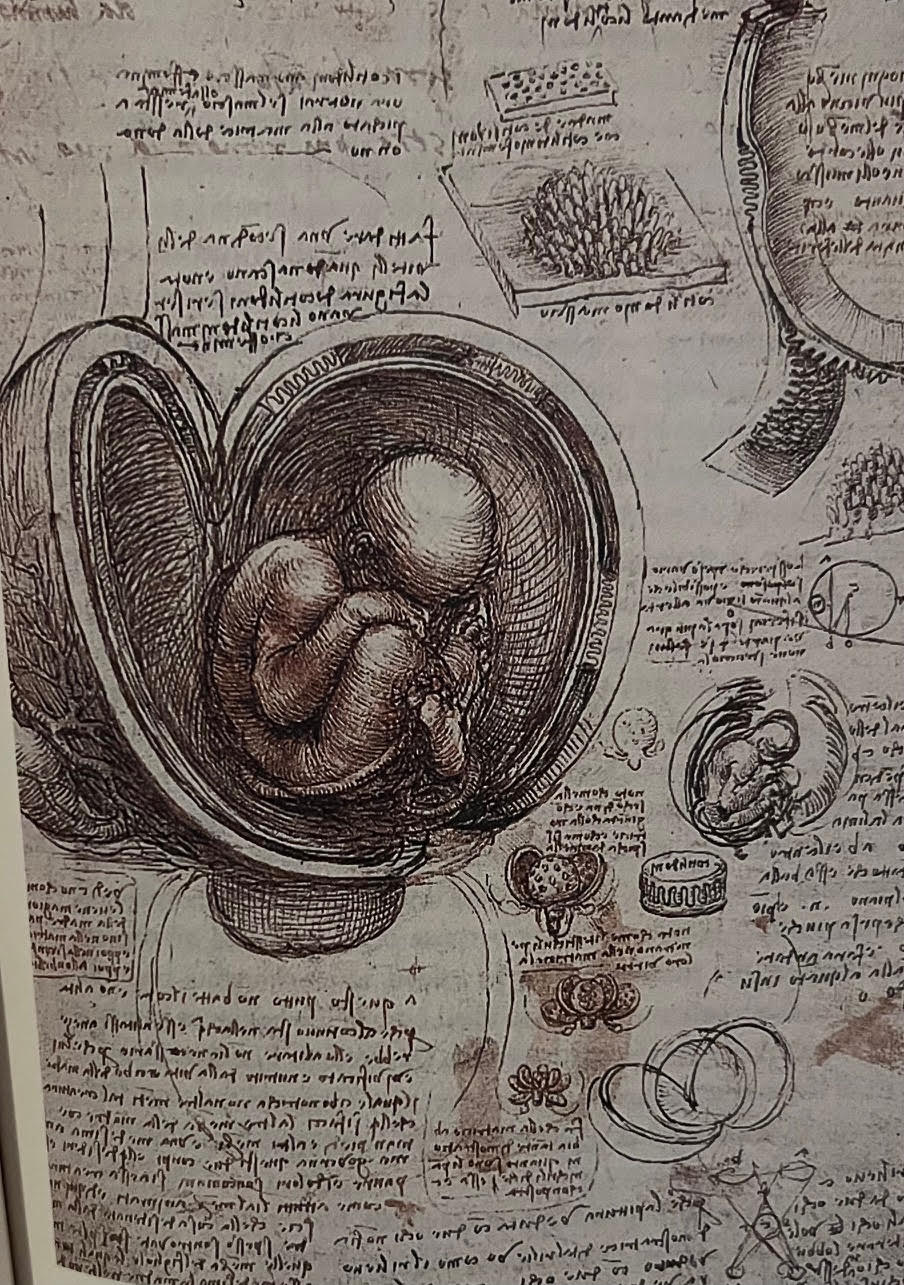

Ch. 14: The Nature of Man

- Another Interest: Anatomy — Yet another one of Leonardo’s interests was human anatomy. Pages and pages of his notebooks are filled with anatomical drawings as he tried to understand how the human body works. At first, he studied anatomy to become better at drawing and painting humans. But eventually, he became obsessed with knowing everything there was to know about the body and mind purely out of curiosity. He wanted to know which nerves controlled which muscles and the exact proportions of every part of the body. He dissected bodies, measured the length of people’s facial features, and recorded observations in his notebooks. These studies helped him depict humans in his work with extreme precision.

Ch. 15: Virgin of the Rocks

- Virgin of the Rocks — This chapter focuses on Virgin of the Rocks, one of Leonardo’s most iconic paintings. Commissioned for a church altar, the work demonstrates Leonardo’s mastery of light, shadow, and perspective to create a lifelike and spiritual scene. The chapter explores the symbolic elements of the painting, including the interplay between nature and divinity, as well as the innovative use of sfumato to blend forms seamlessly. It also explains why two versions of the painting were created.

Ch. 16: The Milan Portraits

- Leonardo’s Portraits — Leonardo drew and painted portraits throughout his lifetime, but many of them were done during his time in Milan serving in the Sforza court. Other than the Mona Lisa, Lady With an Ermine is considered one of his best works. This was a portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, who was a mistress of the Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan. It is believed that Sforza asked Leonardo to paint this portrait in 1489, at the height of their relationship. Another notable portrait was La Belle Ferronnière. This is believed to be a portrait of Lucrezia Crivelli, another of Sforza’s mistresses. Many of Leonardo’s portraits are considered brilliant because of his ability to use shading to make his figures appear three-dimensional and lifelike. He was a master of lighting and shading techniques.

Ch. 17: The Science of Art

- Tapping Into Science — Leonardo believed that painting was an art and a science. He believed that artists should strive to make their paintings lifelike by projecting motion and using various lighting and shading techniques to give off a three-dimensional look. In order to do this, he committed himself to the study of shadows, lighting, color, tone, perspective, optics, and the perception of movement. As with human anatomy, he first began studying these topics to improve his art, but he later immersed himself in the complexities of science for the pure joy of understanding. Below is some information on some of the scientific topics he studied obsessively:

- Lighting & Shadowing — As his career advanced, Leonardo began to understand that the use of shadows, not lines, was the secret to making figures in his paintings appear three-dimensional. As a result, he spent a ton of time studying and writing about shadows in his notebooks. Pages of his notebooks are dedicated to finding out what kind of shadows emerge when light strikes an object at specific angles. Once he determined the results, he used this knowledge strategically in his paintings.

- Quote (P. 266): “He [Leonardo] knew that the essence of good painting, and the key to making an object look three-dimensional, is getting the shadows right, and that’s why he spent more time studying and writing about shadows than he did on any other artistic topic.”

- Quote (P. 267): “Leonardo proceeded to write obsessively about shadows. A torrent of more than 15,000 words on the topic, which would fill 30 pages of a book, still survives, and that is probably less than half of what he originally wrote. His observations, charts, and diagrams became increasingly complex. Using his feel for proportional relations, he calculated the effects of light striking contoured objects at varying angles.”

- Sfumato — As he studied shadows, Leonardo began to understand that there was no such thing in nature as a precisely visible outline or border to an object. He instead insisted that all boundaries are blurred and used shadows and sfumato to define the shape of most of his objects. Sfumato, the practice of using hazy, blurred, smoky outlines rather than sharp lines, is a technique that he pioneered and mastered. The technique is used in most of his work, including his most famous painting, the Mona Lisa.

- Optics — Leonardo studied the science of the eyeball relentlessly. He was obsessed with understanding how the eye perceives light. He conducted detailed dissections of human and animal eyes, sketching their anatomy in his notebooks in order to uncover how light entered and was processed. He also theorized about the behavior of light rays, including how they reflect, refract, and converge. He used the knowledge he gained through these studies to enhance the realism in his art.

- Perspective — Leonardo’s study of optics contributed to his understanding of perspective. As he put it in one of his notebooks, “Painting is based on perspective, and perspective is nothing more than a thorough understanding of the function of the eye.” His notes on perspective are mixed with his notes on optics. Specifically, he explored linear perspective, studying how parallel lines appear to converge at a vanishing point, which he used to create depth and realism in his art. He also investigated aerial perspective, observing how air and mist causes colors and details to fade when we’re looking at an object way out in the distance. This aerial perspective is evident in paintings like The Last Supper and Mona Lisa.

- Lighting & Shadowing — As his career advanced, Leonardo began to understand that the use of shadows, not lines, was the secret to making figures in his paintings appear three-dimensional. As a result, he spent a ton of time studying and writing about shadows in his notebooks. Pages of his notebooks are dedicated to finding out what kind of shadows emerge when light strikes an object at specific angles. Once he determined the results, he used this knowledge strategically in his paintings.

- Chapter Takeaway — One of the major takeaways from this book is how well-studied Leonardo was. He was an extremely curious guy who was always looking for ways to improve his art through learning. His detailed scientific studies of color, shading, perspective, optics, and more helped him become one of history’s greatest artists.

Ch. 18: The Last Supper

- Setting the Table for The Last Supper — The Last Supper is one of Leonardo’s most iconic masterpieces. The assignment came from the Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza, who in 1494 wanted to build a holy mausoleum for himself and his family inside a church located in the heart of Milan. For the north wall of the dining hall, Sforza asked Leonardo to paint the Last Supper, one of the most popular scenes in religious art.

- Painting The Last Supper — The Last Supper depicts the moment just after Jesus tells his 12 apostles, “One of you will betray me,” capturing their shocked and emotional reactions. The painting, approximately 15 feet high and 29 feet wide, covers the north wall of the dining hall in the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan. It showcases everything that made Leonardo brilliant: dynamic motion, masterful lighting and shading, expressive faces, meticulous detail, and intelligent use of perspective. Completed between 1495 and 1498, it is considered one of Leonardo’s greatest masterpieces.

- Deterioration of The Last Supper — Because this was a large painting that needed to cover an entire wall, Leonardo used experimental techniques to execute the painting. Unfortunately, the techniques he tried did not lead to longevity. After just 20 years, the paint began to flake and wither away. By 1550, one of his early biographers reported that the painting was “ruined.” By 1652, the painting was so faint that the monks who lived in the church felt comfortable breaking a doorway through the bottom of the wall. Over the years, there have been six major attempts to restore the painting, many of which have only made the situation worse. Today, it still lives, but it’s hard to tell which parts of the painting are Leonardo’s original work and which parts are cover ups from the various restoration attempts.

Ch. 19: Personal Turmoil

- Leaving Milan — After completing The Last Supper in 1498, Leonardo hit a bit of a rough stretch where he had trouble getting consistent work. In the summer of 1499, the French, led by King Louis XII, took Milan, forcing Duke Sforza to flee. Leonardo got along well with the French, but he ultimately decided to head back home to Florence in 1500 after 17 years in Milan.

Ch. 20: Florence Again

- Back in Florence — Leonardo made Florence his home base for most of 1500 to 1506. In many ways, this period was the most productive of his life. In Florence, he began two of his greatest panel paintings, the Mona Lisa and Virgin and Child with Saint Anne. As an engineer, he found work consulting on buildings and serving the military goals of Cesare Borgia. And in his spare time, he made great progress in his mathematical and anatomical studies.

Ch. 21: Saint Anne

- Virgin and Child With Saint Anne — The Virgin and Child With Saint Anne is considered a masterpiece and one of Leonardo’s best pieces. It was likely commissioned by King Louis XII of France to honor his wife, Anne of Brittany. Completed in 1510 and displayed at the Louvre, this painting combines many elements of Leonardo’s artistic genius: a moment transformed into a narrative, physical motions that match mental emotions, brilliant depictions of the dance of light, delicate sfumato, and a landscape informed by geology and color perspective.

Ch. 22: Paintings Lost and Found

- Mystery Surrounding Leonardo’s Work — Many of Leonardo’s works have been lost over time due to their fragility, his experimental techniques, or the fact that he never signed his paintings. Works like Leda and the Swan survive only through copies or written descriptions. Some pieces have resurfaced after centuries, such as Salvator Mundi, which was rediscovered in the 21st century and became the most expensive painting ever sold at $450 million in 2017. Once in a while, a painting makes headlines for being a possible Leonardo.

Ch. 23: Cesare Borgia

- Working for Borgia — Leonardo began working for Cesare Borgia, the ruthless son of Pope Alexander VI, around 1502. Borgia was one of history’s most violent, devious, and brutal leaders. Acting as Borgia’s military engineer, he traveled across central Italy, inspecting fortresses and creating detailed maps to aid in military strategy. This role allowed Leonardo to merge his artistic skills with his fascination for engineering, producing some of the most advanced maps of his time. Despite Borgia’s notoriety, Leonardo admired the opportunity to apply his talents to real-world challenges, but their collaboration was short-lived, lasting less than a year.

Ch. 24: Hydraulic Engineer

- Interest in Water — Leonardo’s fascination with water led him to become a skilled hydraulic engineer, designing ambitious projects to control and harness its power. He envisioned systems for diverting rivers, creating canals, and preventing flooding. While serving Cesare Borgia, he analyzed the Arno River and assembled a plan to make it navigable, linking Florence to the sea. Like a lot of his ideas, his plans and visions in this area, including his plan for the Arno River, were centuries ahead of their time and therefore did not come to be. He was an unbelievable visionary in many areas of life, including water.

Ch. 25: Michelangelo and the Lost Battles

- Battle of Anghiari — In 1503, Leonardo received an assignment from Florence’s City Hall to paint a victorious battle won by Florence over Milan in 1440 (The Battle of Anghiari). The painting was to cover one-third of a 174-foot wall inside the Palazzo della Signoria in Florence. Based on drawings in his notebooks, it looked like it could have become one of his best paintings. The painting’s central scene featured a frenzy of soldiers attacking each other atop their horses. But, like many of his projects, Leonardo started but did not finish the assignment. We only know this painting through sketches and passages in Leonardo’s notebooks and copies painted by other artists.

- Michelangelo & Leonardo — While Leonardo was working on The Battle of Anghiari, Michelangelo, another one of history’s great artists, was asked to paint a similar battle on the other main wall of the Palazzo della Signoria. A rivalry ensued between the two artists. Michelangelo was almost half Leonardo’s age, and he had become Florence’s hot new artist while Leonardo was in Milan. As painters, Michelangelo and Leonardo were almost complete opposites. Michelangelo was a better sculptor than painter and liked to use sharp, defining lines and borders in his projects. Leonardo was a student of optics, shading, and perspective, which gave his paintings a more realistic, three dimensional feel. In 1504, Michelangelo finished his 17-foot-high statue of David that is considered one of the greatest sculptures ever carved. Like Leonardo, Michelangelo failed to finish his project in Florence; he instead left for Rome to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

- Quote (P. 375): “Michelangelo was good at delineating forms with the use of sharp lines, but he showed little skill with the subtleties of sfumato, shadings, refracted lights, soft visuals, or changing color perspectives.”

- Quote (P. 376): “Michelangelo’s painting has the sharp, delineated outlines that Leonardo, with his love of sfumato and blurred borders, scorned as a matter of philosophy, optics, mathematics, and aesthetics. To define objects, Michelangelo used lines rather than following Leonardo’s practice of using shadows, which is why Michelangelo’s look flat rather than three-dimensional. . . . It is as if he had looked at Leonardo’s method of creating a dusty and hazy battle scene blurred by motion, as well as the sfumatura in Leonardo’s other works, and decided to do just the opposite.”

Ch. 26: Return to Milan

- Back to Milan — In 1506, Leonardo again left Florence for Milan. He briefly returned to Florence a few years later to resolve a dispute with his half-brothers, but he spent the next seven years in Milan. At the time, Milan was under the control of France and King Louis XII, who had named Leonardo his “official painter and engineer.” Although he had a variety of reasons for leaving Florence again, Milan was simply a better place for his intellectual curiosities. In Milan, he enjoyed better opportunities to study the things he wanted to study, and he found fulfillment in his service to King Louis.

Ch. 27: Anatomy, Round Two

- Studying the Body — Leonardo was much more than a painter. He had a wide variety of interests and curiosities, and human anatomy was among the most important to him. From 1508-1513, he poured himself into his anatomical studies, dissecting bodies, drawing breathtaking illustrations of muscles and bones, and writing detailed passages about his findings. His drawing of a human fetus (below) is considered by some art historians to be one of the greatest works of art in the world. During this period, he made discoveries that were revolutionary for his time, but he never published any of his notes. Becoming famous and earning money through published work simply did not motivate him. As was the case with many of his studies, he wanted to know everything about the human body simply for the joy of learning.

- Quote (P. 400): “During this period of intense anatomical study, Leonardo made 240 drawings and wrote at least thirteen thousand words of text, illustrating and describing every bone, muscle group, and major organ in the human body for what would have been, if it had been published, his most historic scientific triumph.”

- Quote (P. 423): “During his frenzied years of work from 1508 to 1513, he seemed never to tire of it [his anatomical work] and kept digging deeper, even though it meant nights spent amid cadavers and the stench of decaying organs.”

- Quote (P. 423): “He [Leonardo] wanted to accumulate knowledge for its own sake, and for his own personal joy, rather than out of a desire to make a public name for himself as a scholar or to be part of the progress of history.”

- Discoveries Involving the Heart — Although he studied every part of the human body, Leonardo’s findings involving the heart were among the most important of his scientific career. At the time, there were many incorrect assumptions about the heart. Through his dissections, Leonardo was among the first to recognize that the heart, not the liver, was the center of the blood system. But his greatest achievement in his heart studies, and all of his anatomical work, was his discovery of the way the aortic valve works. Leonardo discovered that the aortic valve’s opening and closing is influenced by the swirling motion of blood as it flows through the heart, a phenomenon he replicated using glass models and water experiments. This insight into fluid dynamics was centuries ahead of its time and laid the foundation for modern cardiovascular science.

Ch. 28: The World and Its Water

- Water, Geology, and Astronomy — As mentioned many times throughout this book, Leonardo had a wide range of interests that he studied relentlessly. Water, geology, and astronomy were among them. His fascination with water extended beyond simply hydraulics to studying its role in shaping the natural world. He observed how rivers carve landscapes, how water cycles through evaporation and rain, and how ocean tides are influenced by the moon. His notebooks include hundreds of detailed drawings of turbulent currents and whirlpools. Leonardo studied Earth’s geology, correctly theorizing that shifting tectonic plates caused mountains to rise. He also studied astronomy closely, correctly finding that the moon’s light is a reflection of the Sun’s rays. He correctly hypothesized that the sky is blue due to particles in the air scattering the Sun’s light waves.

Ch. 29: Rome

- Time in Rome — In 1513, Leonardo left Milan for Rome, where he’d spend the next several years. Interestingly, he did not create a lot of art during this time. For as talented as he was at painting and drawing, the case could be made that Leonardo was more interested in science and engineering than he was art. His time in Rome was mostly spent pursuing his interests in anatomy, water systems, and engineering.

- Quote (P. 457): “Baldassare Castiglione, an author and courtier who knew Leonardo in Rome, described him as one ‘of the world’s finest painters, who despises the art for which he has so rare a talent and has set himself to learn philosophy [meaning the sciences].’”

Ch. 31: The Mona Lisa

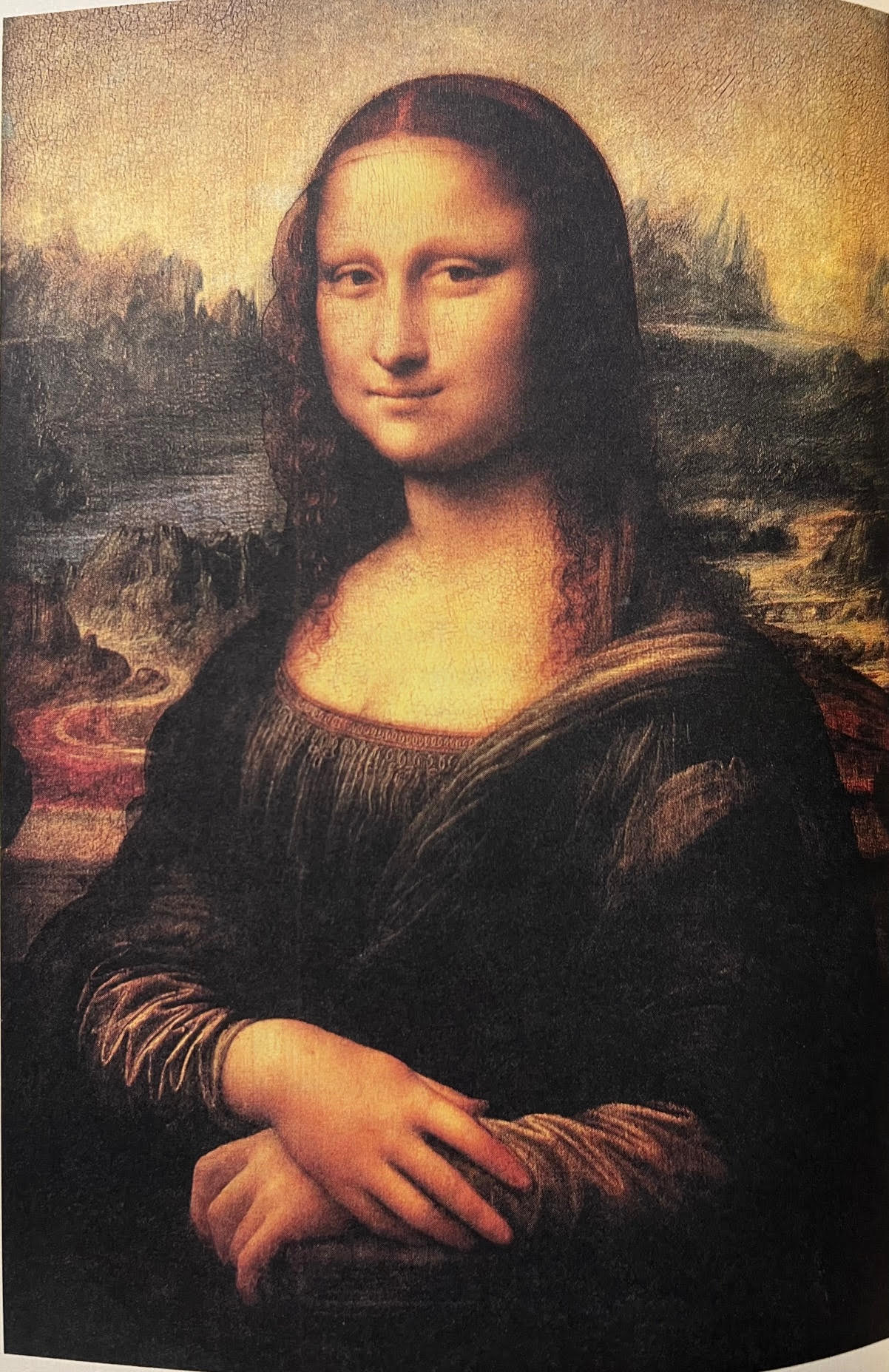

- The Mona Lisa — The Mona Lisa by Leonardo is among the most iconic paintings in the world. Leonardo began work on it in 1503, when he returned to Florence after serving Cesare Borgia. He carried the painting with him for the rest of his life, constantly adding small details and strokes of paint. It was never delivered to anybody, and it was in his studio when he died in 1519. Today, it is on display in the Louvre. The assignment was to paint 24-year-old Lisa del Giocondo, who was the wife of a famous and wealthy silk merchant. The painting is considered a masterpiece and a culmination of Leonardo’s studies of optics, shading, astrology, the environment, and perspective. Lisa’s slight smile is a prominent feature of the painting that has helped captivate audiences for centuries. Leonardo also painted the eyes in a way that makes it seem like Lisa is staring at you, no matter where you move.

Ch. 32: France

- France & Death — In 1516, Leonardo moved to France at the invitation of King Francis I, who admired him as both an artist and an intellectual. The king appointed him “First Painter, Engineer, and Architect to the King.” During his time in France, Leonardo focused on organizing his many notebooks, sketching architectural designs, and exploring engineering projects rather than creating new paintings. Although his health was declining, he remained intellectually active, discussing ideas with the king and his court. Leonardo passed away on May 2, 1519 at the age of 67.

Conclusion

- Trained Genius — Throughout the book, Isaacson makes the case that Leonardo was a trained genius rather than a prodigy who was blessed with unworldly talent. I agree with that assessment. Although he did possess incredible natural talent for drawing and writing, Leonardo was a student of life who built a wide-ranging skillset and knowledge base through intense study and observation. He was far more than a painter, with interests that included art, science, anatomy, astronomy, engineering, hydrology, flight, birds, optics, and much more. He studied many of these subjects to improve his painting skills, but his interest usually turned into an obsessive quest to quench his insatiable curiosity. He simply loved to learn and pushed himself to understand the world. We can all learn from his desire to learn as much as possible; every day should be spent trying to improve and grow.

- Quote (P. 519): “But none painted the Mona Lisa, much less did so at the same time as producing unsurpassed anatomy drawings based on multiple dissections, coming up with schemes to divert rivers, explaining the reflection of light from the earth to the moon, opening the still-beating heart of a butchered pig to show how ventricles work, designing musical instruments, choreographing pageants, using fossils to dispute the biblical account of the deluge, and then drawing the deluge. Leonardo was a genius, but more: he was the epitome of the universal mind, one who sought to understand all of creation, including how we fit into it.”

- Quote (P. 519): “He [Leonardo] was not graced with the type of brilliance that is completely unfathomable to us. Instead, he was self-taught and willed his way to his genius. So even though we may never be able to match his talents, we can learn from him and try to be more like him. His life offers a wealth of lessons.”

- Quote (P. 520): “Leonardo actually did have special talents, as did Einstein, but his distinguishing and most inspiring trait was his intense curiosity. He wanted to know what causes people to yawn, how they walk on ice in Flanders, methods for squaring a circle, what makes the aortic valve close, how light is processed in the eye and what that means for the perspective in a painting. He instructed himself to learn about the placenta of a calf, the jaw of a crocodile, the tongue of a woodpecker, the muscles of a face, the light of the moon, and the edges of shadows. Being relentlessly and randomly curious about everything around us is something that each of us can push ourselves to do, every waking hour, just as he did.”