Dopamine Nation

Anna Lembke

GENRE: Health & Fitness

GENRE: Health & Fitness

PAGES: 304

PAGES: 304

COMPLETED: July 2, 2023

COMPLETED: July 2, 2023

RATING:

RATING:

Short Summary

We’re living in a time of unprecedented access to high-reward, high-dopamine stimuli: drugs, food, streaming, social media, alcohol, gaming, texting, TikTok, and more. In Dopamine Nation, Dr. Anna Lembke explains why we need to keep dopamine in check and how to do it.

Key Takeaways

Favorite Quote

“The basic principle of exposure therapy is to expose people in escalating increments to the very thing — being in crowds, driving across bridges, flying in airplanes — that causes the uncomfortable emotion they're trying to flee, and in doing so, augment their ability to tolerate that activity. In time they may even come to enjoy it.”

Book Notes

Introduction

- Addicted Nation — Over time, we have transformed from a world of scarcity (where food literally had to be hunted down) to a world of overwhelming abundance. There are an incredible number of highly rewarding stimuli available to us today: drugs, food, news, gambling, shopping, gaming, texting, sexting, social media. The smartphone has fueled this transition. The result is a world filled with addiction.

- Dopamine — Dopamine is what leads to feelings of pleasure, satisfaction, and motivation. When you feel good that you have achieved something, it’s because you have a surge of dopamine in the brain. Scientists consider dopamine to be a kind of universal currency for measuring the addictive potential of any experience. The more dopamine in the brain’s reward pathway, the more addictive the experience.

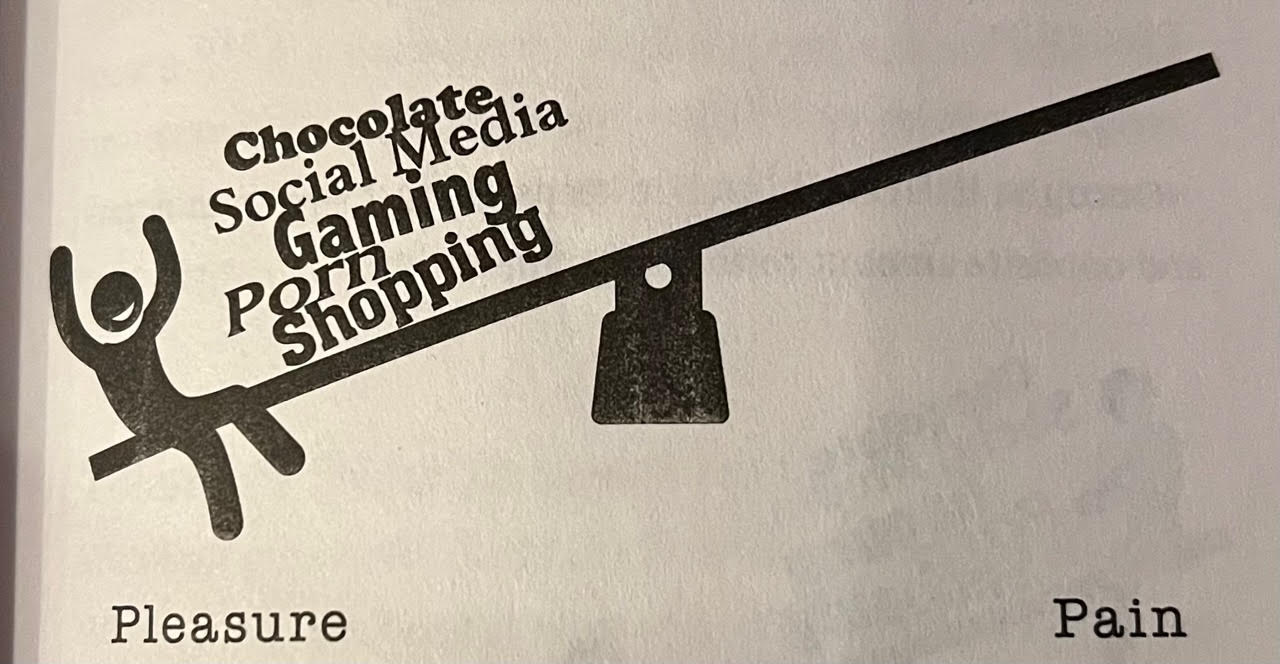

- Dopamine & Pain — In addition to the discovery of dopamine, one of the most remarkable neuroscientific findings in the past century is that the brain processes pleasure and pain in the same place. Further, pleasure and pain work like opposite sides of a balance; when you experience a moment of craving more of something, that moment of wanting is the brain’s pleasure balance being tipped to the side of pain.

Ch. 1: Our Machines

- Access Drives Addiction — One of the biggest risk factors for getting addicted to anything is easy access to that thing. When it’s easier to get the thing, we’re more likely to try it, which means we’re more likely to get addicted to it. The opioid addiction that has developed over the last century is a good example of this. The quadrupling of opioid prescribing (OxyContin, Vicodin, Fentanyl) in the United States between 1999-2012, combined with widespread distribution of those opioids to every corner of America, led to rising rates of opioid addiction and related deaths. Genetics and environment are also powerful drivers of addiction.

- Morphine, Heroin, and Fentanyl — In 1805, Friedrich Sertürner discovered the painkiller morphine — an opioid alkaloid 10 times more potent than its precursor opium. In an attempt to find a less addictive opioid painkiller to replace morphine, chemists came up with a brand-new compound, which they named heroin. Heroin turned out to be 2-5 times more potent than morphine. Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid, is 50-100 times more potent than morphine.

- Addictions Are Everywhere — Whether it’s opioids, cannabis, food, alcohol, or internet-related things like pornography, social media, gambling, and video games, we have created a world where addiction is everywhere. These addictions are also more easily accessible than ever before.

- Chapter Takeaway — Because so many dopamine-provoking items and activities are available to us, and so easily accessible, we’ve become a nation filled with addiction everywhere you look. Accessibility is the top driver of addiction — when something is easily accessible to you, you are more likely to try it and potentially abuse it.

Ch. 2: Our Machines

- Avoiding Pain — We are all running from pain. Whether it’s drugs, streaming services, music, food, alcohol, or anything else, many of us are abusing certain outlets to escape our own pain and discomfort. When raising kids, we’ve become more protective than ever, refusing to allow our children to face any form of adversity. All of this running from pain, rather than addressing the core issue, is ultimately causing us problems and making us more miserable. Anxiety and depression are up considerably since the 1980s despite huge improvements in technology and overall quality of life. We mask our pain and discomfort rather than facing it.

Ch. 3: Our Machines

- Dopamine Discovery — Dopamine was first discovered as a neurotransmitter in the human brain in 1957 by two scientists working independently: Arvid Carlsson of Lund, Sweden and Kathleen Montagu of London, England. It is known as the neurotransmitter most associated with motivation to get a reward and the pleasure of a reward. Dopamine is used to measure the addictive potential of any behavior or drug. The more dopamine a drug releases in the brain’s reward pathway, and the faster it releases dopamine, the more addictive the drug. High-dopamine substances and activities release more dopamine in our brain’s reward pathway.

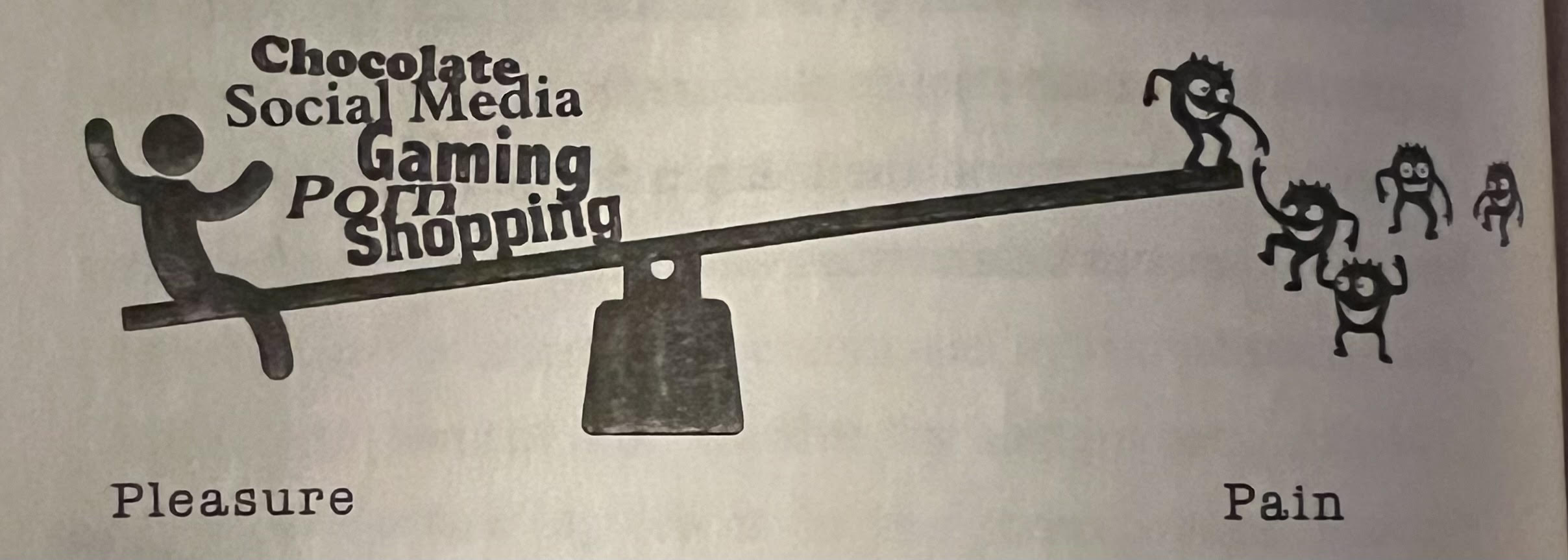

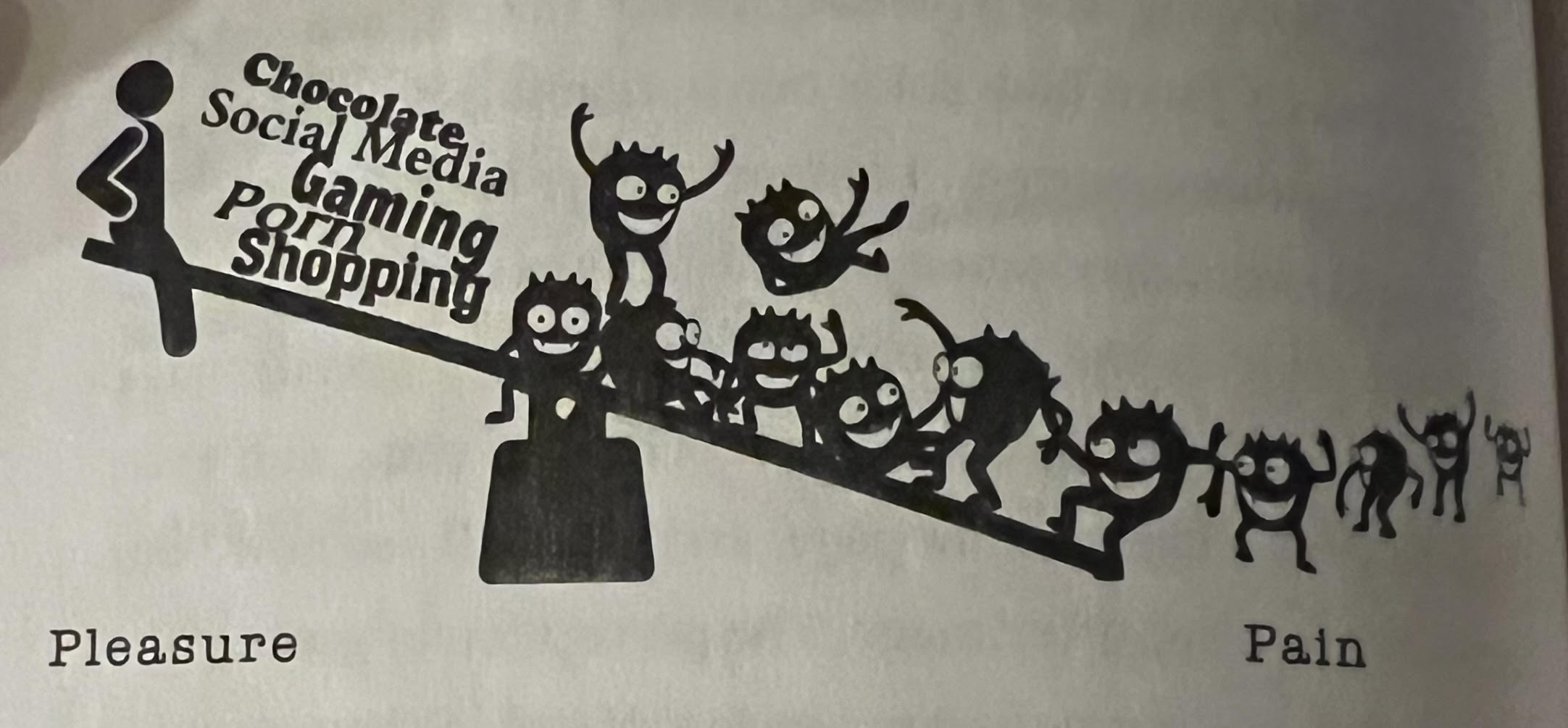

- Pleasure & Pain: A Balancing Act — Neuroscientists have determined that pleasure and pain are processed in overlapping brain regions and work like a balance beam. When we experience pleasure, dopamine is released in our reward pathway and the balance tips to the side of pleasure. But the balance wants to remain level, so every time it tips toward pleasure, self-regulating mechanisms kick into action to bring it level again. These are like little gremlins that stack up on the side of pain to bring the balance back to level, and then even further until it tips to the side of pain.

- Quote (P. 52): “In the 1970s, social scientists Richard Solomon and John Corbit called this reciprocal relationship between pleasure and pain the opponent-process theory: ‘Any prolonged or repeated departures from hedonic or affective neutrality… have a cost.’ That cost is an ‘after-reaction’ that is opposite in value to the stimulus. Or as the old saying goes, What goes up must come down.”

- Takeaway — When you do something that releases dopamine in the brain, you will naturally come back to balance, or even to the side of pain. This is why, when you eat fast food, it feels great at first (dopamine release), but later you feel crappy for doing it (the balance tipping back to level or to the side of pain). It’s the brain’s natural tendency to bring things back to even.

- Quote (P. 52): “In the 1970s, social scientists Richard Solomon and John Corbit called this reciprocal relationship between pleasure and pain the opponent-process theory: ‘Any prolonged or repeated departures from hedonic or affective neutrality… have a cost.’ That cost is an ‘after-reaction’ that is opposite in value to the stimulus. Or as the old saying goes, What goes up must come down.”

- Tolerance & Addiction — The more we indulge in something that releases dopamine in the brain and brings us pleasure, the more of a tolerance we build for the substance or activity. That is, with repetition, our gremlins get bigger, faster, and more numerous, and we need more of the substance or activity to get the same effect. Tolerance is an important factor in the development of addiction. After enough use or indulgence, the balance scale gets completely weighted to the side of pain because we don’t get the same big dopamine spike from the activity anymore. Our capacity to experience pleasure goes down and our vulnerability to pain goes up.

- Takeaway — The more you indulge in something that releases dopamine and brings you a lot of pleasure, the more you build up a tolerance for it. You end up needing more of it just to get the same dopamine release, and eventually you don’t get much of a dopamine release at all. In this state, the balance completely shifts to the side of pain. You are now addicted and you don’t even get much pleasure from the substance or activity. Instead, you just feel miserable in the form of anxiety, insomnia, irritability, withdrawal, etc. You now need the substance of activity just to feel balanced (normal).

- Anticipation Dopamine — In many cases, we actually get more of a dopamine release in the brain when we are anticipating a reward than we do when we actually experience the reward. This explains why, for example, we sometimes feel more pleasure looking forward to a big summer vacation than we do when we’re actually on the vacation. It also explains why dopamine levels in the brain will skyrocket once we actually get an anticipated reward (“we’re in Hawaii!”) and will take a huge plunge if we end up not getting the anticipated reward (trip is cancelled last second).

- Pavlov’s Dogs — The idea of anticipatory dopamine traces back to Ivan Pavlov, who won a Nobel Prize in 1904 for demonstrating that dogs reflexively salivate when presented with a slab of meat. When Pavlov paired the presentation of meat with the sound of a buzzer, he found that the dogs would salivate at the sound of a buzzer, even when there was no meat. The dogs were anticipating the meat (the reward) when they heard the buzzer (an environmental cue). This experiment showed that dopamine releases are often even stronger when we are anticipating a reward than when we actually get the reward.

- Chapter Takeaway — Things that lead to pleasure and a surge in dopamine also lead to pain. The more you engage in a certain activity or substance that gives you pleasure, the more of a tolerance you build, meaning you then have to engage in the activity or substance even more just to produce the same type of feeling.

Ch. 4: Dopamine Fasting

- Recovering From Addiction — When recovering from an addiction, most people go on a ‘dopamine fast.’ This usually involves abstaining from the drug or activity that they are addicted to in order to restore balance between pain and pleasure.

Ch. 5: Space, Time, and Meaning

- Self-binding — This is the idea of making things difficult on yourself to engage in a certain substance or activity that you’re addicted to. For example, if playing video games is a bad habit that you’re addicted to, you can unplug the console and put it in your closet after playing it. This will make it that much harder to find the motivation to play it the next day. It’s all about putting barriers in place to prevent you from being whisked away by emotion and desire.

- Quote (P. 92): “If we wait until we feel the compulsion to use, the reflexive pull of seeking pleasure and/or avoiding pain is nearly impossible to resist. In the throes of desire, there’s no deciding. But by creating tangible barriers between ourselves and our drug of choice, we press the pause button between desire and action.”

- Takeaway — When you are addicted to something and get a dopamine surge from engaging in it, emotion often takes over and reason goes out the window. Even when you know that what you’re doing is wrong, you still do it because you get overtaken by the surge in dopamine you get from doing the activity. This is why you have to put self-binding barriers in place to stop you from doing what you know you shouldn’t be doing. You can’t rely on yourself. If it’s time to read a book but you’re addicted to your phone, lock the phone in another room.

- Quote (P. 92): “If we wait until we feel the compulsion to use, the reflexive pull of seeking pleasure and/or avoiding pain is nearly impossible to resist. In the throes of desire, there’s no deciding. But by creating tangible barriers between ourselves and our drug of choice, we press the pause button between desire and action.”

- Physical Self-binding — This refers to creating physical barriers — like the video game example above — to prevent yourself from participating in a bad habit or activity. Simply make it difficult on yourself to do the thing you want to stop doing.

- Weight Loss Surgery — Weight loss surgeries like gastric banding, sleeve gastrectomy, and gastric bypass are designed to help patients lose weight from their frame. These surgeries effectively create a smaller stomach and/or bypass the part of the gut that absorbs calories. In a way, these are physical self-binding surgeries.

- Gastric Band Surgery — The gastric band puts a physical ring around the stomach, making it smaller without removing any part of the stomach or small intestine.

- Sleeve Gastrectomy Surgery — The sleeve gastrectomy surgically removes part of the stomach to make it smaller.

- Gastric Bypass Surgery — Gastric bypass surgery reroutes the small intestine around the stomach and duodenum, where nutrients are absorbed.

- Gastric Bypass & Alcohol — Many patients who get gastric bypass surgery become addicted to alcohol. This is likely because a food addiction is what drove them to become obese and require the surgery in the first place. Now that they have the weight off, they shift their addiction to alcohol to keep their new figure. Additionally, the surgery alters how alcohol is metabolized, increasing the rate of absorption. The absence of a normal-size stomach means alcohol is absorbed into the bloodstream almost instantaneously and avoids the first-pass metabolism that usually occurs in the stomach. As a result, patients get intoxicated faster and stay intoxicated longer on less alcohol. It’s like they are getting an alcohol IV.

- Overconsumption & Boredom — One variable contributing to the problem of overconsumption and dopamine is the growing amount of leisure time we have today, and the boredom that comes with it. As we’ve streamlined manufacturing, agriculture, domestic chores, and many other previously time-consuming, labor intensive jobs, we’ve unlocked more time for leisure. We have more time on our hands than ever before, and many people fill those hours with high-dopamine activities involving entertainment.

- Chapter Takeaway — It’s very difficult to resist the temptations of something you are addicted to. Put barriers in place to prevent yourself from doing something you know you shouldn’t be doing. Make it difficult to do the thing you know you shouldn’t be doing.

Ch. 6: A Broken Balance

- Opioids: How They Work — Opioids, sometimes called narcotics, are prescribed to help people who are in severe pain. Opioids attach to proteins called opioid receptors on nerve cells in the brain, spinal cord, gut, and other parts of the body. When this happens, the opioids block pain messages sent from the body through the spinal cord to the brain. Opioids deliver a high and help patients feel better, but they can be highly addictive, especially as you build up tolerance over time. Below are the various types of opioids. Heroin is a highly, highly addictive opioid that is illegal and has no medical benefit whatsoever.

- Codeine

- Fentanyl

- Hydrocodone

- Oxycodone

- Oxymorphone

- Morphine

- Heroin

- Problems With Medicating — Although medications to treat various mental and physical disorders are helpful tools, there are a few problems worth noting. The first is that any drug that induces feelings of pleasure (opioids) has the potential to be addictive. Second, it’s possible that some of these medications don’t work like they’re supposed to and could actually make you worse off in the long run. The evidence for psychotropic medications is not very robust, especially when looking at the long run. Many people have reported feeling worse in some way after long-term opioid, antidepressant, anti-anxiety drug use.

- Quote (P. 129): “Despite substantial increases in funding in four high-resourced countries (Australia, Canada, England, and the US) for psychiatric medications like antidepressants (Prozac), anxiolytics (Xanax), and hypnotics (Ambien), the prevalence of mood and anxiety symptoms in these countries has not decreased (1990 to 2015). These findings persist even when controlling for increases in risk factors for mental illness, such as poverty and trauma, and even when studying severe mental illness, such as schizophrenia.”

- Quote (P. 135): “Please don’t misunderstand me. These medications can be lifesaving tools and I’m grateful to have them in clinical practice. But there is a cost to medicating away every type of human suffering, and as we shall see, there is an alternative path that might work better: embracing pain.”

- Medication & Demographics — Psychiatric drugs and opioids are prescribed more often and in larger amounts to poor people than any other demographic. Americans on Medicaid, a federally funded health insurance program for the poorest and most vulnerable people, are prescribed opioid painkillers at twice the rate of non-Medicaid patients. Medicaid patients die from opioids at 3-6 times the rate of non-Medicaid patients.

- Quote (P. 133): “In medicating ourselves to adapt to the world, what kind of world are we settling for? Under the guise of treating pain and mental illness, are we rendering large segments of the population biochemically indifferent to intolerable circumstance? Worse yet, have psychotropic medications become a means of social control, especially of the poor, unemployed, and disenfranchised?”

- Chapter Takeaway — Medication to treat physical and mental problems can be very useful, especially in the short term. But over the long haul, attempting to “medicate problems away” isn’t the best approach. For one, some drugs have the potential to be addictive. Second, the drugs might actually be making you worse in various ways in the long run. Your best bet is to address the problem head on rather than masking it with medication. Ideally, medication is more of a bandaid to get you through a rough stretch rather than a permanent long-term solution.

Ch. 7: Pressing on the Pain Side

- Embracing Pain & Exposure Therapy — Rather than using medication as a bandaid, the best approach is to tackle the problem head on by facing it directly. Embrace pain. If you have anxiety about talking to strangers, for example, slowly start talking to more strangers. By consistently exposing yourself to your fears, you get better and better and begin to feel more comfortable over time. This is exposure therapy, and it’s perhaps the best strategy to overcoming a fear. Anxiety medication, in this case, is ultimately just a bandaid. You have to go in and address the issue at its core. Do the things that make you uncomfortable!

- Quote (P. 157): “The basic principle of exposure therapy is to expose people in escalating increments to the very thing — being in crowds, driving across bridges, flying in airplanes — that causes the uncomfortable emotion they’re trying to flee, and in doing so, augment their ability to tolerate that activity. In time they may even come to enjoy it.”

- Quote (P. 160): “Pain to treat pain. Anxiety to treat anxiety. This approach is counterintuitive, and exactly opposite to what we’ve been taught over the last 150 years about how to manage disease, distress, and discomfort.”

- Ice Baths — In the 1820s, a German farmer named Vincenz Priessnitz promoted the use of ice-cold water to cure all kinds of physical and psychological disorders. With the development of modern plumbing and heating, we now have access to hot showers and baths, but cold water used to be the only option back in the day.

- Ice Bath Comeback — Ice baths are making a comeback in the 21st century. Researchers have shown that immersing in ice cold water (around 50 degrees and below) produces elevations in monoamine neurotransmitters (e.g. dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin), the same neurotransmitters that regulate pleasure, motivation, mood, appetite, sleep, and alertness. These elevations typically continue for well after the cold water bath. The cold water also helps reduce swelling in the body. In this way, a morning ice bath can have a lot of great mental and physical health benefits.

- Exercise! — Exercise increases many of the neurotransmitters involved in positive mood regulation: dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, epinephrine, endocannabinoids, and endogenous opioid peptides (endorphins). It’s the No. 1 best thing you can do for your mental, physical, and emotional health.

- Quote (P. 152): “A key to well-being is for us to get off the couch and move our real bodies, not our virtual ones. As I tell my patients, just walking in your neighborhood for thirty minutes a day can make a difference. That’s because the evidence is indisputable: Exercise has a more profound and sustained positive effect on mood, anxiety, cognition, energy, and sleep than any pill I can prescribe.”

- Takeaway — You have to make exercise — cardio, weights, balance, and stability — a priority in your life. The benefits you get from doing it consistently are vast and wide-ranging. It’s a great investment of time.

- Quote (P. 152): “A key to well-being is for us to get off the couch and move our real bodies, not our virtual ones. As I tell my patients, just walking in your neighborhood for thirty minutes a day can make a difference. That’s because the evidence is indisputable: Exercise has a more profound and sustained positive effect on mood, anxiety, cognition, energy, and sleep than any pill I can prescribe.”

- Anhedonia — Anhedonia is the inability to experience pleasure from activities usually found enjoyable. In other words, it’s a lack of joy with daily life. This is seen a lot in skydivers, celebrities, and professional athletes; when these people no longer participate in the activities/career that delivered such unusual highs, they often experience anhedonia when they return back to a “normal” life. They were so accustomed to the thrills of their high-profile, thrill-seeking life.

- Workaholics — The “flow” of deep concentration often created while working is a drug in itself, releasing dopamine and creating its own high. People who are workaholics often experience this and can become addicted to it. It’s an escape. This kind of single-minded focus is heavily rewarded in many modern nations, but it’s also dangerous because it can prevent you from forming deep, intimate connections with friends and family. Ultimately, these relationships are far more important in life.

- Chapter Takeaway — Rather than relying on medication to mask various issues, you are better off putting in the time and effort to address a problem or fear directly. Get comfortable with being uncomfortable. Push yourself to do things that scare you. By consistently exposing yourself to your fears, you will build up a level of comfort to the point of not being afraid of them at all. It’s not easy — it takes a lot of work and courage.

Ch. 8: Radical Honesty

- Be Honest — Tell the truth and be honest with yourself and others. It’s one of the best character qualities you can develop. Honesty helps you become aware of your actions, develop deep connections with people, and keeps yourself accountable/prevents you from forming a victim mindset and blaming others.

- Quote (P. 182): “Telling the truth draws people in, especially when we’re willing to expose our own vulnerabilities. This is counterintuitive because we assume that unmasking the less desirable aspects of ourselves will drive people away. It logically makes sense that people would distance themselves when they learn about our character flaws and transgressions. In fact, the opposite happens. People come closer. They see in our brokenness their own vulnerability and humanity.”

- Prefrontal Cortex — The prefrontal cortex is the frontmost part of your brain, just behind the forehead, and is involved in decision-making, emotion regulation, and future planning, among many other complex processes. It’s also a key area involved in storytelling.

- Take Accountability — One of the great benefits of being honest with yourself is that it allows you to fully understand what you’re good at and what you need to improve. It also prevents you from blaming everyone and everything for your problems like most people. You’re able to better understand the role you’ve played in where you are in life and where you can improve to get better.

- Chapter Takeaway — Be honest! When you’re honest and forthcoming with people, they respect you and actually like you more, even if what you share with them seems bad.