Central Banking 101

Joseph Wang

GENRE: Business & Finance

GENRE: Business & Finance

PAGES: 225

PAGES: 225

COMPLETED: July 13, 2023

COMPLETED: July 13, 2023

RATING:

RATING:

Short Summary

Central banks like the Federal Reserve in the United States have a lot of power and influence over monetary policy, the stock market, and the economy as a whole. In Central Banking 101, Joseph Wang discusses the key functions of the Fed.

Key Takeaways

Favorite Quote

“As the price of a stock rises, it becomes a bigger part of an index and so more money needs to be allocated to it, reinforcing the upward momentum. In a market dominated by passive investment, companies with large market caps become even bigger. This is exactly what is seen in the incredible outperformance of large cap tech companies like Microsoft or Apple. Not coincidentally, the two companies happen to be members of all three major equity indexes: the Dow Jones, S&P 500, and Nasdaq.”

Book Notes

Ch. 1: Types of Money

- Types of Money — There are four main types of money to note. In a functional financial system, all four forms of money are freely convertible to each other. When that conversion breaks down, serious problems emerge. The four types of money include:

- Fiat Currency — This is the typical rectangular-shaped paper bill decorated with a historical figure. A $100 bill (or any bill) is issued by the Federal Reserve.

- Bank Deposits — A bank deposit is an “IOU” from a bank that can become worthless if the bank goes bankrupt. It’s the number you see in your bank account. Bank deposits can be seamlessly converted to fiat cash at a bank or an ATM. The government provides $250,000 in FDIC deposit insurance for bank account holders.

- Central Bank Reserves — This is a special type of money issued by the Fed that only commercial banks can hold. Much like a customer’s bank deposit is an “IOU” from a commercial bank, a central bank reserve is an “IOU” from the Fed. Commercial banks can convert their central bank reserves to fiat cash by calling up the Fed and asking for a shipment of currency. Commercial banks use central bank reserves when they pay each other or anyone else who has a Fed account, and they use fiat currency or bank deposits to pay everyone else. Banks cannot lend out their central bank reserves to customers.

- Treasuries — These are securities issued by the U.S. government. It’s basically a type of money that also pays interest. If you are a large institutional investor or an individual with a ton of money, you aren’t eligible to hold central bank reserves because you aren’t a bank and it wouldn’t make sense for you to put all of your money in a commercial bank because it would far exceed FDIC insurance limits. For these people/entities, treasuries are a good option to place your money.

- Bank Balance Sheets — For a bank, assets include things like loans handed out to customers and invested securities that generate cash flow. Liabilities include things like a customer’s bank deposit (because they owe the customer) and debt.

- Central Bank Reserves — Central bank reserves are created when the central bank buys financial assets or makes loans. The central bank is the only entity that can create central bank reserves, so the total amount of reserves in the financial system is completely determined by central bank actions. For example, when the Fed purchases $1 billion in U.S. Treasury securities, it creates $1 billion in central bank reserves to pay for them. That happens whether the seller of the Treasuries is a commercial bank or a nonbank. If the Fed bought the Treasury security from a commercial bank, then the commercial bank’s Treasury security asset is exchanged for central bank reserves.

- Quantitative Easing — This occurs when the Fed tries to influence market interest rates by buying longer-dated Treasuries. By buying these Treasuries from commercial banks, they give the banks reserves that they can then use to loan money to customers, which sparks the economy. The reverse happens when the Fed sells Treasuries to banks, which reduces the banks’ available money supply.

- Bank Deposits — Bank deposits are created when a commercial bank creates a loan or when it buys a financial asset. They are destroyed when the loan or asset is repaid. Since commercial banks create deposits out of thin air to cover their loans and asset purchases, they tend to have many more deposits than central bank reserves on their balance sheet. So when you see that a bank has a significant number of bank deposits, remember that it’s mostly an indication of how many loans are being made by the bank.

- Quote (P. 20): “Bank deposits are created when a commercial bank creates a loan or when it buys a financial asset. A common misconception is that a bank takes in deposits and then lends those deposits out to other people. Rather than lend out deposits, a bank simply creates bank deposits out of thin air when it makes a loan. This is very similar to the way a central bank acts when it creates central bank reserves. The central bank acts as a bank to commercial banks, and commercial banks act as a bank to nonbanks like individuals and corporations.”

- Banking Crisis — A banking crisis occurs when a bank has made too many bad loans and becomes insolvent. When that happens, a bank’s deposits may no longer be able to be converted to currency at their stated value (i.e. a $100 deposit can’t be converted to $100 in currency). Depositors will then panic and try to withdraw at the same time, which forces the bank to sell some of its Treasuries/other securities at a discount in order to give depositors their withdrawal amounts. All of this together sends the bank into a free fall and leads to a bank crisis.

- Treasuries — Treasuries are issued by the federal government and are the dominant form of money in the financial system because they are safe, liquid, and widely accepted. Treasuries are essentially money for large investors because they offer these individuals/institutions an easy way to store large amounts of money safely. Unlike the other three forms of money, Treasuries offer interest and also fluctuate in market price based on supply and demand, but you will not be affected if you hold them until maturity. It’s only when you sell before the maturity date that you are exposed to gains or losses based on market prices. Treasuries play a big role in the Fed’s monetary policy approach — the Fed buys and sells Treasuries to expand and restrict money supply in the economy.

- Fiat Currency — This is paper bills. Straight cash, homie. It’s printed and guaranteed by the government. Anybody can convert their bank deposits to currency at an ATM, so banks keep a good amount of currency in their vaults. If they need more, they convert their central bank reserves to cash by calling the Fed, which then sends armored vehicles loaded with currency to the bank.

- Interesting Fact — With 15 billion $100 dollar bills floating around the world, the $100 bill is the most common bill in circulation. There is over $2 trillion in currency circulating around the world, and that number continues to climb despite the popularity of electronic payments. From a dollar value perspective, around 80% of the $2 trillion in circulation is held in the form of $100 bills.

- U.S. Dollar Dominates Abroad — One of the reasons we rarely see $100 bills is because a good amount of them are held abroad. The reality is that the U.S. dollar is the most trusted and widely used form of currency in the world. Wealthy people in developing countries (e.g. Argentina) often prefer to store part of their wealth in the U.S. dollar because their home countries are often poorly managed and have double-digit inflation rates. In fact, some countries like El Salvador completely pass on their own monetary policy and use the U.S. dollar as their official currency. Drug cartels have also been found to hold massive amounts of U.S. dollars because they are easily transportable and hard to trace. All of this has made the U.S dollar the dominant form of currency in the world.

- Quote (P. 32): “Globally, (U.S.) dollar currency is held internationally as a store of value, like gold during the gold-standard era. We currently live in a dollar-standard world, where the U.S. dollar is widely accepted throughout the world and perceived to be safe. This led to a boom in offshore dollar banking, but also in offshore demand for dollar currency.”

- Takeaway — Many people and countries around the world trust and are highly dependent on the U.S. dollar. Our currency is the most used currency in the world for its overall safety and reliability.

- Quote (P. 32): “Globally, (U.S.) dollar currency is held internationally as a store of value, like gold during the gold-standard era. We currently live in a dollar-standard world, where the U.S. dollar is widely accepted throughout the world and perceived to be safe. This led to a boom in offshore dollar banking, but also in offshore demand for dollar currency.”

- Chapter Takeaway — There are four types of “money.” Everything is good when all four are working fluidly in the financial system. Problems arise when one or more of these is experiencing issues.

Ch. 2: The Money Creators

- Money Creators — There are three creators of money in our financial system: the Fed, commercial banks, and the Treasury. These three work together to create and move money in the economy. This chapter discusses the role of each entity.

- The Fed — The Fed has just two jobs: (a) full employment in the economy and (b) provide stable prices by managing inflation. The Fed’s inflation target is 2% annually, but there’s no set number that represents full employment in the economy. To meet its two goals, the Fed manipulates interest rates and prints money.

- r* (“r star”) — There is an interest rate that leads to perfect balance in the economy where we are neither expanding or contracting. When interest rates are below r*, the economy is expanding, inflation is rising, and unemployment is ticking lower. When interest rates are above r*, the economy is slowing, inflation is declining, and unemployment is ticking higher. The Fed employs a small army of economists to determine where the level of r* is at the moment, and then sets out to either lower or raise interest rates to achieve balance in the economy.

- Manipulating Interest Rates — When the economy is in trouble, the Fed will do everything possible to get interest rates down to promote economic growth and spending. To do this, the Fed first cuts its target overnight interest rates to zero so banks can borrow money for cheap. They will then buy lots of Treasury securities, which will drive up the price of the Treasuries and therefore lower their yields. When yields are down, interest rates in the market are down because the return on a risk-free security (a Treasury security) is down. By buying Treasuries from banks, the Fed is also forcing the banks to take in more money that they can then lend out to customers. This approach is called quantitative easing.

- Quote (P. 40): “QE essentially converts Treasuries into bank deposits and reserves, thus forcing commercial banks as a whole to hold more of their money in the form of central bank reserves, and it forces non-banks as a whole to hold more of their money in the form of bank deposits… Forced to trade in their Treasuries for bank deposits, nonbanks can trade their bank deposits for higher-yielding corporate debt or speculate on equity investments. Banks, who have more limited investment options due to regulation, may trade their reserves for higher-yielding Agency MBS (mortgage-backed securities). The portfolio rebalancing among nonbanks and banks pushes asset prices higher.”

- Takeaway — By buying Treasury securities and forcing banks to take on more money in the form of reserves, the Fed is basically lowering the price of Treasury securities and forcing banks and other big institutional investors to go out and buy stocks, which drives up the price of the stock market and other financial assets. The Fed is also encouraging banks to lend more money to customers, which drives up spending in the economy.

- Quote (P. 40): “QE essentially converts Treasuries into bank deposits and reserves, thus forcing commercial banks as a whole to hold more of their money in the form of central bank reserves, and it forces non-banks as a whole to hold more of their money in the form of bank deposits… Forced to trade in their Treasuries for bank deposits, nonbanks can trade their bank deposits for higher-yielding corporate debt or speculate on equity investments. Banks, who have more limited investment options due to regulation, may trade their reserves for higher-yielding Agency MBS (mortgage-backed securities). The portfolio rebalancing among nonbanks and banks pushes asset prices higher.”

- Commercial Banks — Banks create/make money by profiting off the spread between what they pay in interest to customers who deposit money at the bank and the interest rate they charge to customers who are lending money (e.g. mortgage loan). In this way, a bank’s assets are the loans it gives out and its liabilities are customer deposits. Retail customers and big institutional investors can deposit money at the bank, but banks prefer more retail customers because they can get away with paying these customers a lower interest rate — they are less likely to pull their money out and go elsewhere. Banks have to pay big institutions a higher interest rate because these institutions are more likely to go to a different bank if a better interest rate is available. Overall, there are two main issues a bank faces:

- Solvency — Solvency involves making sure the loans the bank gives out are high quality. Banks are highly leveraged — a bank only needs $5 of its own money to create $100 of loans. When things go well and a borrower is making regular loan payments, the bank can make interest on $100 of loans even if it only invested $5. But if the borrower defaults on the loan, then the bank takes a big loss because of how leveraged it is. If this happens a lot, the losses pile up and the bank can become insolvent and may have to file for bankruptcy. The highly leveraged nature of banks means they can earn a lot of money but can also go bankrupt quickly. This is why banks are careful about who they lend to.

- Liquidity — Liquidity means making sure the bank has enough money on hand. Banks have to make sure they have enough central bank reserves to settle payments with other banks (in case one bank needs to transfer a customer’s money to a different bank) while also having enough on hand to convert customer deposits to fiat currency (in case customers withdraw their money). This can be a problem for a bank that has little reserves or currency on hand and whose assets are illiquid, meaning they can’t be sold easily or quickly. In some of the bank failures of 2023, there were banks that didn’t have enough reserves and had too much money tied up in Treasuries that lost value when the Fed raised interest rates. When customers began to withdraw in a panic, these banks had to sell their Treasuries at deep losses to get enough money to pay customers who withdrew their money.

- The Treasury — The Treasury Department is the part of the U.S. government that collects taxes and issues Treasury securities. The Treasury doesn’t decide how much debt to issue — that is decided by the federal government’s deficit, which is a result of decisions by Congress. Through legislation, Congress determines the federal government’s spending (outflows) and its tax revenues (inflows), the difference is which is the deficit. The Treasury then issues short and long-term securities to fund the deficit. The Treasury issues trillions of dollars in securities every year to help fund the government deficit.

- Chapter Takeaway — Money is created and distributed in the financial system through the Fed, commercial banks, and the Treasury.

Ch. 3: Shadow Banks

- Shadow Banks — The term “shadow bank” sounds mysterious, but these are just non-commercial bank businesses that engage in banking-like activities. The basic business model of shadow banks is to use shorter-term loans to invest in longer-dated assets. This mismatch creates an opportunity for profit because longer-term interest rates are usually higher than shorter-term interest rates. The number of shadow banks has grown significantly over the years, to the point there they have become more common and influential than the traditional commercial banking system. Types of shadow banks include:

- Primary Dealers — Primary dealers are a group of dealers that have the privilege of trading directly with the Fed. They are the heart of the financial system, and the Fed conducts its monetary operations through primary dealers. For example, when the Fed is conducting quantitative easing by buying Treasuries it only buys from primary dealers. There are around 24 primary dealers, all affiliated with large foreign or domestic banks. Dealers are like supermarkets for financial products. A supermarket buys a whole assortment of goods from producers, stores them, and then sells them at a markup to consumers. In the same way, a dealer stands ready to buy a wide range of financial products like corporate bonds or U.S. Treasuries, then holds on to them until it can find other investors willing to buy the products. Dealers allow investors to buy and sell securities with ease; without them there would be no financial system.

- Money Market Mutual Funds — Think SPAXX! A money market fund is a special type of investment fund that invests only in short-term securities and allows investors to withdraw their money at any time and gain access to it basically immediately. Money market shares are basically like bank deposits that often pay a little more interest. Investors park their money in money market funds, get paid market interest rates (rather than near zero rates in bank savings accounts), and withdraw whenever they want. They are very liquid and are a great place to put money when you need it soon.

- Exchange Traded Funds (ETF) — ETFs are investment funds whose shares are traded on an exchange like a stock. An ETF takes an investor’s money and uses it to purchase assets such as stocks, bonds, or commodity futures that mirror a certain index. For example, an S&P 500 Index ETF would issue shares and use the proceeds to buy the stocks underlying the S&P 500 Index. The goal with ETFs is to replicate an index (like the S&P 500) so the fund moves in step with the index without a manager buying and selling securities (like a mutual fund).

- Mortgage REITS — Mortgage REITS are investment funds that invest in mortgage-backed securities, usually ones that are guaranteed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac. They are classic shadow banks that take out very short-term loans to invest in very long-term assets.

- Private Investment Funds — These are funds, such as hedge funds or private equity funds, that take investor money and invest in a broad spectrum of financial assets. They usually employ a very wide range of strategies, so it is difficult to generalize them. Many of these funds use fairly aggressive investing strategies.

- Chapter Takeaway — Shadow banks refer to funds and entities that are fairly well-known and are a big part of the financial system.

Ch. 4: The Eurodollar Market

- Eurodollars & The Bretton Woods Agreement — Eurodollars are U.S. dollars held outside the U.S. They are called Eurodollars because the first off-shore dollars appeared in Europe in 1956. Global demand for U.S. dollars grew for several reasons, including the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1944, which created a new monetary system by shifting the world from a gold standard to a U.S. dollar standard. Widespread use of the dollar also grew as the U.S. became more and more dominant.

- Why the U.S. Dollar? — There are offshore markets for euros, yen, and other currencies, but none come close to the size of the offshore U.S. dollar market. The amount of dollar borrowing by nonbanks residing outside the U.S. is around $13 trillion! There are a few reasons the U.S. dollar is the dominant currency around the world:

- Safety — The U.S. dollar is widely considered to be a safe haven. The U.S. dollar is backed by the world’s strongest military, largest economy, a functioning legal system, and a central bank (the Fed) that has kept inflation under control for decades. Many other countries struggle with this. Extremely high inflation and poor government management lead to chaos and instability in many other countries. Argentina, for example, has experienced consistent inflation in the 10-50% range in last years. As a result, many Argentinians hold their savings in U.S. dollars.

- Trade — Because if its safety and reliability, global trade basically operates on a U.S. dollar standard, where 50% of global trade is invoiced in dollars and 40% of international payments are made in dollars. The dollar is used in global trade even when neither party is American. When Japan imports oil from Saudi Arabia, for example, they pay in U.S. dollars. There is a very strong “network effect” for U.S. dollars; everyone accepts the dollar, so everyone holds them.

- Lower Cost — Foreigners sometimes like to borrow money in dollars because the interest rates on dollar loans or bonds are often lower than on their home currency.

- Liquidity — Capital markets using the dollar are the deepest and most liquid in the world. Because there are so many markets around the world using the dollar, it’s easier to access dollars than any other currency. This also opens up access to more investors who prefer to use the dollar.

- Easy to Store — Storing large sums of money risk-free is difficult, even for very wealthy people in the U.S. (FDIC insurance only covers so much). For big investors around the world, storing a lot of dollars is easier than trying to put away large sums of money in other forms of currency. A deep and liquid U.S. Treasury market means investors can easily store U.S. dollars risk-free. This is why China owns trillions of dollars in Treasuries (China is our biggest debtor) — they have no alternative. There is no other market deep enough to hold all that money reliability and without risk. So they park their money in Treasuries traded in U.S. dollars.

- Offshore Dollar Banking — To summarize, most of the world uses the U.S. dollar because of its safety and reliability. Recognizing this, global banks (not too many U.S. banks, interestingly) set up shop around the world and make loans using U.S. dollars. These banks can usually set fairly high interest rates because the big international institutions and companies that borrow dollars from these banks (there aren’t too many “everyday guy” international retail customers) don’t really have any great alternative options for their currency needs. These banks can go bankrupt quickly because the big companies and institutions that borrow from them do not have great insurance covering their money in the bank, meaning they will take their money out and run at the first sign of trouble. When this happens, these global banks get into trouble quickly.

- 2008 Financial Crisis & Banks — The 2008 financial crisis was centered on the banking system. Banks gave out bad loans to low-quality borrowers, who then defaulted on those loans and forced the banks to sell the homes at fire sale prices. When retail customers began to sense trouble, they started withdrawing money, forcing banks to sell other assets at a loss to pay withdrawing customers. This led asset prices around the country to fall, which fueled more panic. All of it was made worse by the fact that banks held very little in their reserves. Strict regulations are now in place to hold banks in check. Basel III was put in place to make banks safer by forcing them to hold high-quality liquid assets like Treasuries and encouraging them to loan money to high-quality borrowers.

- FDIC Fees — The government provides $250,000 in FDIC deposit insurance for bank account holders. The government funds this program by charging FDIC fees to banks. Banks are forced to pay these fees using a percentage of their total assets.

- Death by the Dollar — Because dollars are used by almost everyone around the world, the U.S. government, through its control of the U.S. banking system, has tremendous global power. Banks or individuals who are blacklisted from the dollar banking system are not able to send or receive dollars through commercial banks anywhere in the world. For a bank or any other big entity, this is basically a death sentence. Iran, which has been sanctioned by the U.S., now must sell its oil for payment in gold.

- U.S. Abandons the Gold Standard — In 1971, the U.S. abandoned the gold standard, a monetary system in which currency was backed by gold, to curb inflation and prevent foreign nations from overburdening the system by redeeming their dollars for gold. Though a lesser form of the gold standard continued until 1971, its death had started centuries before with the introduction of paper money — a more flexible instrument for our complex financial world. Today, the price of gold is determined by the demand for the metal.

- Chapter Takeaway — The U.S. dollar is by far the world’s dominant form of currency. It’s reliable, it’s safe, it’s trusted, and it’s backed by a global superpower (the U.S.). These are characteristics that we take for granted in the U.S., but they are luxuries to many people and countries abroad who deal with extremely high inflation and government instability. The U.S. banking system is very involved around the world, and the U.S. government — through its control of the U.S. banking system — has a lot of global power.

Ch. 5: Interest Rates

- Interest Rates — Interest rates are the building blocks of all asset prices in the market, and they are heavily influenced by the Fed. Mortgage rates, other loan interest rates, stocks, bonds, and many other things are influenced by moving interest rates, which can be thought of as the cost of borrowing money. When interest rates are low, it’s cheaper to borrow money when taking out a loan, bond yields are generally low (which leads people to invest in stocks, sending the stock market up), and people are spending more money in the economy. Things are good. When interest rates are high, people are less encouraged to take out a loan, bond yields are higher (leading more people to invest in these almost risk-free assets rather than the riskier stock market), and the public is generally spending less money in the economy.

- Interest Rates & Treasury Yields — The interest rate everyone looks at as a foundational starting point is Treasury yields. The returns on Treasuries are basically risk-free because they are backed by the government. Every other potential investment someone is considering will be based on the return offered by Treasuries. If you can get a 4% return on a Treasury security, you’re going to take that over a 5% return from a stock or real estate investment because it’s much safer. But if the gap is 2% vs. 7%, you’re going to go with the riskier 7% option because it offers much more upside on your money. In this way, Treasury yields are the basis on which all risky investments are judged.

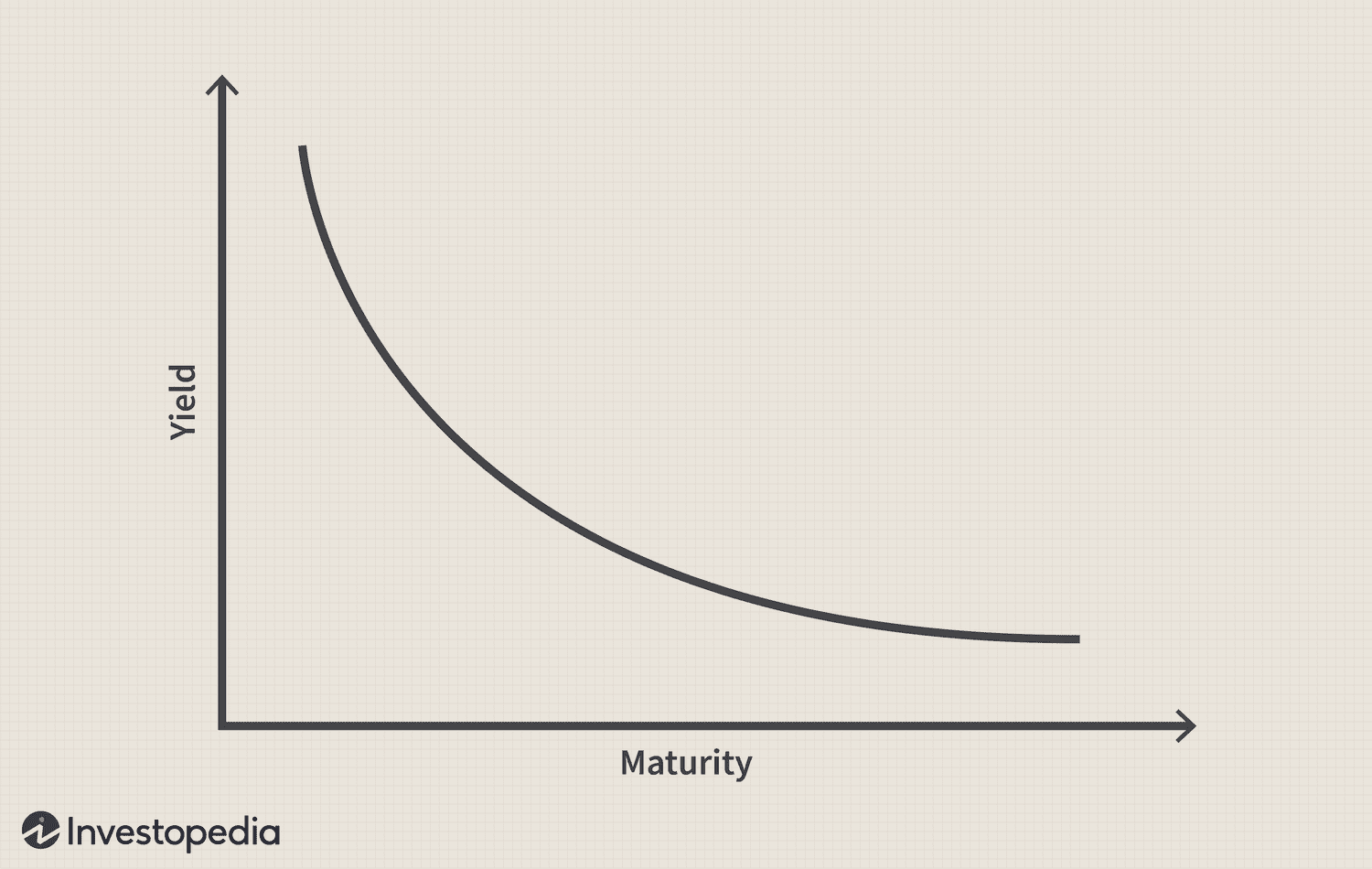

- The Fed & the Treasury Yield Curve — Through its Treasury buying and selling activity, the Fed has tremendous influence on these foundational Treasury yields, especially short-term Treasury offerings. The Treasury yield curve charts interest rates on all Treasury offerings, covering all of the various Treasury offerings with ranges of 1-30 years. The curve tends to be upward sloping, which means longer-dated Treasury bonds have higher yields than shorter-term offerings (because they require an investor to hold their money in the asset longer). If the slope is inverted, it usually means we could be heading for a recession (more on this in a later bullet). Overall, the Treasury yield curve offers a great way to tell what the market is thinking about the Fed’s next move, as well as the market’s expectation for economic growth and inflation.

- Short-term Interest Rates — The Fed has a lot of control over short-term interest rates, while long-term interest rates are driven more by market conditions. The Fed controls short-term interest rates in two ways that are connected to each other:

- Federal Funds Rate — This is the rate commercial banks pay to take out overnight loans for reserves. Put another way, the federal funds market is an interbank market where commercial banks borrow reserves from each other on an overnight basis, often to meet certain reserve requirements. Market participants use the federal funds rate as a basis for what 3-6-month interest rates will be. For example, if the Fed sets the federal funds rate at 1%, then the interest rate of any 3-month loan is going to be at least 1% otherwise the lender would just lend at 1% every night risk-free. It’s important to note that the federal funds market (overnight lending between banks to meet reserve requirements) has died down considerably. Quantitative easing and a regulation called Basel III have made it so banks have plenty of reserves on hand and generally don’t need to dip into the federal funds market to meet reserve requirements. This means the federal funds rate is a little less influential on overall interest rates in the market than it used to be.

- Reverse Repo Facility (RRP) — Because banks typically hold very high levels of reserves these days, the Fed controls the federal funds rate by adjusting the interest rate it offers on the Reverse Repo Facility (RRP) and the reserves banks hold in their Fed account. The RRP offers market participants (money market funds, primary dealers, commercial banks, etc.) the option of lending to the Fed at the RRP offering rate. This RRP rate puts a floor on what these entities would offer as an interest rate to the public. For example, if a bank can loan to the Fed at a 2% RRP interest rate, then it would never lend to the public at less than 2%. Through the RRP rate it pays on reserves, the Fed makes sure the federal funds rate stays within its target range. Prior to the financial crisis of 2008, the Fed did not pay interest on reserves.

- Federal Funds Rate, RRP, and Treasury Yields — Market participants use the overnight rate (federal funds rate, RRP) set by the Fed as a reference to value what the 1-week, 1-month, 2-month, etc. Treasury yield should be. Assuming the Fed is not expected to adjust its target federal funds range, market participants will expect these short-term risk-free rates on Treasuries to be slightly higher than the overnight risk-free rate; otherwise, the lenders would just lend overnight consecutively while preserving the option of pulling their money back any day they want. Longer-term Treasuries are far less affected by the federal funds and RRP rate.

- Quote (P. 110): “The Fed’s firm control over overnight rates allows it to exert control along the Treasury yield curve, though its influence declines rapidly as tenors increase.”

- Takeaway — My interpretation on all of this is that the federal funds and RRP rate set by the Fed sets a floor for yields on short-term Treasuries. Treasury yields must be a decent amount higher than the federal funds and RRP rates, otherwise market participants like commercial banks will just lend overnight to the Fed forever and always. With Treasury yields a decent amount higher, they will invest in those securities because they are also very safe. In this way, the Fed controls yields on short-term Treasury offerings.

- Quote (P. 110): “The Fed’s firm control over overnight rates allows it to exert control along the Treasury yield curve, though its influence declines rapidly as tenors increase.”

- Longer-term Interest Rates — While the Fed has a lot of control over short-term interest rates on Treasuries, long-term interest rates are more a result of the overall market and economic conditions. Expectations for the path of short-term interest rates (will they go up or down?), an additional premium (for locking your money into a long-term security), and economic conditions (e.g. supply and demand) are the key drivers of long-term interest rates on Treasuries.

- Path of Short-term Interest Rates & Eurodollar Futures — Eurodollar futures offer a good way of seeing what the market thinks short-term interest rates will be in the future. Of all the financial instruments, Eurodollar futures are the most reflective of economic fundamentals. Eurodollar traders know the Fed will react according to how the economy performs, so they focus on hard economic data even as other asset classes are stuck in moments of euphoria or fear. In other words, the people who determine Eurodollar futures study the Fed and the economy really closely and determine what they think the Fed will do regarding short-term interest rates. There are four major Eurodollar futures contracts in each calendar year that take the name of their month of expiry: March, June, September, and December. Eurodollars contracts are available for many years into the future, so a market participant can easily see what the market thinks short-term interest rates will be far into the future.

- Supply and Demand — Supply and demand is one of the economic factors that impacts long-term interest rates. The supply of Treasuries is determined by the federal government’s deficit. A bigger deficit usually, but not always, means more Treasuries. Demand is tough to gauge as well because Treasuries are purchased by investors around the world, with foreign demand in part determined by for foreign monetary policies and foreign trade policies. In recent years, negative rates in Japan and the Eurozone have increased demand for U.S. Treasuries, which continue to offer positive returns. China and Japan both hold over $1 trillion in U.S. Treasuries. Domestically, the Fed is the biggest purchaser of Treasuries.

- Shape of the Yield Curve — In addition to the level of yields, the shape of the Treasury yield curve (discussed in a previous bullet) is also an important watch point for investors. The yield curve can be used to gauge the market’s perception of the state of the economy. Market participants often focus on an inverted yield curve — one where longer-term yields (usually the 10-year Treasury) are lower than short-term yields (usually the 2-year Treasury or 3-month T-Bill) — as a sign that the economy will “soon be in recession.”

- Quote (P. 118): “Recall, longer-term rates are driven in part by the market’s expectation of the future path of short-term interest rates. When longer-term interest rates are lower than short-term interest, then the market is expecting the Fed to lower short-term rates soon. That imminent rate cut is already being reflected in the pricing of longer-dated Treasuries. The market thinks the Fed will cut rates soon because it perceives economic weakness that will prompt the Fed to take action. Participants in the bond market are very sophisticated and extremely sensitive to economic conditions, so their judgements are not to be taken lightly. In practice, the market will often, but not always, sniff out economic weakness before the Fed figures out what is happening.”

- Takeaway — When the Treasury yield curve is inverted, returns on longer-term Treasuries are lower than short-term Treasuries. This means the market believes the Fed will cut interest rate and has priced that in to long-term Treasuries (which is why their returns are low). Why would the market think the Fed is cutting rates soon and why is this considered a predictor of an upcoming recession? Because the bond market senses weakness in the economy and believes the Fed will need to cut interest rates to encourage spending and stimulate the economy.

- Quote (P. 118): “Recall, longer-term rates are driven in part by the market’s expectation of the future path of short-term interest rates. When longer-term interest rates are lower than short-term interest, then the market is expecting the Fed to lower short-term rates soon. That imminent rate cut is already being reflected in the pricing of longer-dated Treasuries. The market thinks the Fed will cut rates soon because it perceives economic weakness that will prompt the Fed to take action. Participants in the bond market are very sophisticated and extremely sensitive to economic conditions, so their judgements are not to be taken lightly. In practice, the market will often, but not always, sniff out economic weakness before the Fed figures out what is happening.”

- Chapter Takeaway — Interest rates have an impact on almost everything in the economy. They affect the stock and bond market, the real estate market, and they generally encourage or discourage consumer spending. The Fed controls interest rates by setting the federal funds and RRP rate and through its buying and selling of Treasuries from market participants like commercial banks. An inverted yield curve is a sign that a recession might be coming.

Ch. 6: Money Markets

- Money Markets — Money markets (not money market funds) are markets for short-term loans with maturities that range from overnight to a year. They are the plumbing of the financial system — they keep everything working but are largely out of sight. Money markets involve overnight swaps of vast amounts of money between banks and the U.S. government. The majority of money market transactions are wholesale transactions that take place between financial institutions and companies. Banks often borrow from money markets to fund longer-term asset purchases. When money markets break down, these banks can’t roll over their short-term debt and are forced to sell their assets to repay their money market loans.

- Money Markets: Secured — There are two types of money markets: secured and unsecured. Since the 2008 financial crisis, unsecured money markets — where nothing is put up as collateral for the loan — have become far less important. In secured money markets, a borrower puts up a financial asset as collateral for a short-term loan. There are two segments of secured money markets:

- Repurchase (Repo) Market — Repo loans are secured by securities such as Treasuries, corporate bonds, mortgage-backed securities, and equities. With repo transactions, a borrower “sells” a security to a lender while at the same time entering into an agreement to buy back the same security at a future date at a slightly higher price. The prices of these transactions will be lower than the market value of the underlying security to give the lender a little bit of a safety cushion. In practice, most repo transactions are overnight loans collateralized by safe assets like U.S. Treasuries. The repo market is enormous, with around $1 trillion in overnight loans made against Treasuries every day. Money market funds are the primary lenders in the repo market.

- Foreign Exchange (FX) Swap Market — The FX-swap market is a market for foreign currency loans. FX-swap transactions are like repo transactions, but instead of securities the collateral used is foreign currency. For example, a 3-month Euro-USD FX swap would be borrowing euros using U.S. dollars as collateral. Ultimately, the FX-swap market allows investors to obtain foreign currency and hedge out exchange risk. It’s a big market with daily volume around $3.2 trillion. Lenders of U.S. dollars in this market tend to be domestic commercial banks, U.S. investors who are looking to invest in foreign assets with foreign currency, and foreign central banks looking to earn a return on the U.S. dollars they hold in their reserves.

- Money Markets: Unsecured — Unsecured money markets are markets for short-term loans where the promise to repay is backed by nothing other than confidence in the borrower. These loans tend to offer higher interest rates than secured loans because of the higher risk involved. The largest segment of unsecured money markets is certificates of deposit (CDs), which are essentially deposits that cannot be withdrawn until they reach a preset maturity date. Commercial paper (CP) is also a big part of the unsecured money market world.

- Chapter Takeaway — Money markets are really important and an under-appreciated pillar of the financial system. They keep things running smoothly through their short-term debt offerings.

Ch. 7: Capital Markets

- Capital Markets — Capital markets are where borrowers (e.g. companies) go to borrow from investors rather than commercial banks. Capital markets can be thought of as having two components: equity and debt markets. Equity markets are where a company offers ownership stake in the company in exchange for funding. The investor’s money grows or shrinks based on the company’s stock price. Although they don’t say it outright, there is evidence that the Fed makes decisions based on the status of the stock market. Debt markets are where a company or government entity offers an “IOU” in change for an investment of money that will be repaid with interest at a later date (maturity date).

- Equity Markets — Equity markets (e.g. the stock market) are crazy. They’re the most widely talked about markets, but they are very emotional and are actually the least reflective of true economic conditions. When you buy a share of a company, you own part of that company. Investors usually use either fundamental or relative valuation approaches when looking at stocks. Fundamental valuation involves the discounted cash flow model where the investor forecasts future earnings and discounts them back to today using a discount rate. Relative valuation involves comparing a company’s fundamentals (including stock price) to other companies in the same industry.

- Quote (P. 148): “The difficulty with using valuation to predict the future price of a stock is that there are many ways of valuing a stock and it is not clear that one method is consistently better than others.”

- Rise of Passive Investing — The overall structure of equity markets has changed significantly over the past two decades due to the rise of passive investing. More and more Americans are investing in the stock market through their retirement plans at work rather than doing their own valuations and choosing their own stocks. These retirement plans often offer target date funds and index funds that don’t invest based on stock valuation analysis. These funds instead dump money into various stocks at regular intervals (every paycheck period) regardless of their price. Over the last two decades, flows from these passive investors have grown to become the driver of the equity market. This has several very, very important implications:

- Stocks Move Higher — Every week/paycheck period there is a constant flow of new money entering the stock market as employer retirement plans get additional money from employee paychecks to invest in various funds, even if valuations are considered to be sky high. This means the stock market is generally always climbing higher and higher over time.

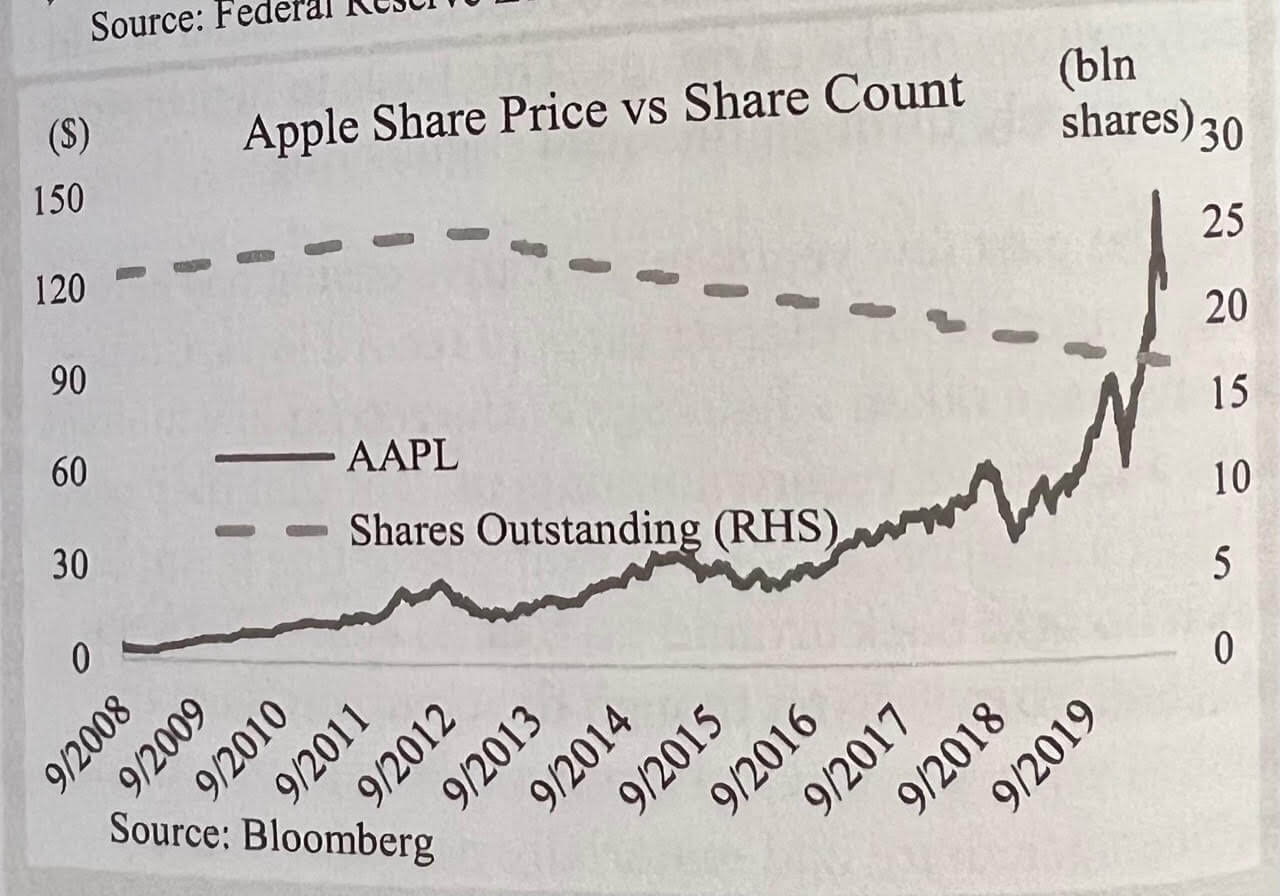

- Big Market Cap Stocks Thrive — Stocks with large market capitalizations benefit the most from this passive investing sequence because they are often included in index funds that seek to track big indexes like the S&P 500, and retirement plans pour most employee money into these relatively safe index funds. Additionally, the bigger a company’s market cap, the more money goes to that company when a retirement plan deposits more money into the index fund. All of this means high market cap stocks are going to move higher and higher. Apple is a perfect example of this because it’s included in all three of the major indexes: the Dow, the S&P 500, and the Nasdaq.

- Quote (P. 150): “As the price of a stock rises, it becomes a bigger part of an index and so more money needs to be allocated to it, reinforcing the upward momentum. In a market dominated by passive investment, companies with large market caps become even bigger. This is exactly what is seen in the incredible outperformance of large cap tech companies like Microsoft or Apple. Not coincidentally, the two companies happen to be members of all three major equity indexes: the Dow Jones, S&P 500, and Nasdaq.”

- Value Investing Is Broken — Value investing used to be the holy grail. Benjamin Graham and others were big proponents of value investing via stock analysis, but valuations have simply become less important today due to the huge amount of money flowing into the stock market from passive investing. Any stock not included in one of the major indices is at a big disadvantage. It doesn’t mean they can’t appreciate, but it’s just harder for them to do so compared to a company like Apple that is receiving huge flows from retirement plans at regular intervals (every employee paycheck).

- Quote (P. 150): “Cheap companies, which tend to be smaller companies, are largely absent from the major stock indices that receive passive investor flows. These value companies thus continue to underperform. The active investors that look for value cannot compete with the constant torrent of retirement money that drives major stock indices higher.”

- Takeaway — It’s almost not worth taking the time to research, locate, and invest in undervalued stocks. They are at a disadvantage compared to big market cap stocks that are receiving consistent investment inflows from retirement plans that are taking money from employee paychecks and pouring it into index funds that are designed to track the major indices. In the end, investing in big market cap stocks and ETFs that track the indices might be the best option.

- Quote (P. 150): “Cheap companies, which tend to be smaller companies, are largely absent from the major stock indices that receive passive investor flows. These value companies thus continue to underperform. The active investors that look for value cannot compete with the constant torrent of retirement money that drives major stock indices higher.”

- Equity Markets: Private Equity — The equity market is more than just the stocks listed on an exchange; non-publicly traded private equity is also part of it. Companies that turn to private equity decide to forgo an IPO that would take them public and allow them to raise money from a large pool of investors. Instead, they raise money through the private markets by offering equity for sale to accredited investors. These tend to be medium or small companies. They sell ownership interest in the company to institutional investors. Think Shark Tank! The people who pitch on Shark Tank are small-medium business owners who are looking to raise money from accredited investors (the sharks) via private equity.

- Liquidity Problems — One of the big problems with private equity is how illiquid it is. With publicly-traded companies, an investor can simply sell shares on an exchange in a matter of seconds. With private equity ownership, it’s hard to find somebody to buy your ownership interest once you have it. You would have to find another wiling investor, explain the investment, and hope that he buys it. It’s a lot more difficult, and it’s why many companies ultimately do go public.

- Debt Markets — Debt markets are less glamorous than equity markets, but are much bigger: if the debt market is a store, the equity market is an aisle. Debt markets are where companies and governments go to raise money via debt by issuing bonds. The debt market is more complex than the equity market because companies usually only have one kind of public stock but have several issues of debt. Some of it could be long-term, some short-term; some could be slotting rate, some fixed rate. There’s also unsecured and secured, as well as callable and noncallable, and more.

- Evaluating Bonds — Market participants usually evaluate bonds in terms of their yields vs. the yield of a Treasury security. For example, a 5-year bond issued by Microsoft would be evaluated by how much additional yield it offers over 5-year Treasuries because Treasuries are considered risk-free investments. The Microsoft bond would need to offer a decently better yield for an investor to consider the opportunity. A few risks of bonds include:

- Credit Risk — How likely is the company to go bankrupt and default? Credit ratings are the best signal for assessing this. Large investors rely on these ratings heavily. The higher a company is rated, the lower the interest rate they can offer on their bonds. The lower a company is rated, the more interest they must offer to convince investors to take the extra risk with their capital

- Liquidity Risk — This is the risk that you won’t be able to sell your bond before the maturity date very easily.

- The Bond Market: A Smart Market — The bond market is considered the “smarter” market vs. the equity markets because it is more sensitive to economic fundamental. Whereas the stock market swings wildly based on the public’s emotions, the bond market is more reflective of what’s actually going on in the economy. Deteriorations in a company’s fundamentals will quickly be reflected in the company’s bond prices, but not necessarily in its equity prices. There are three main segments of the bond market: Treasury securities, mortgage-backed securities, and corporate debt.

- Corporate Bonds — Corporate bonds are held by a wide range of investors, the largest of which are insurance companies, pension funds, mutual funds, and ETFs. Broadly speaking, the market is divided into an investment-grade universe (bonds rated BBB and above and a high-yield universe (bonds rated below BBB-, also known as junk bonds). According to S&P, around 85% of corporate bonds are investment grade and the rest are high yield. Corporate bond ETFs hold a diversified portfolio of corporate bonds but issue shares that are traded actively throughout the day like a stock.

- Fast Growth — In recent years, interest rates have been very low. This has led to an explosion of corporate bonds. Companies have been able to issue bonds and pay very little in interest on those bonds because of the low market interest rates. This is why so many of them have issued corporate bonds in the last few years, and it’s why the number of corporate bonds has gone up so much.

- Stock Buybacks & Low Interest Rates — One of the best ways a company can increase its stock price is to buy back its own stock in the open market. This move increases earnings per share and sends the stock price up right away. When interest rates are very low, companies can really have fun because they can issue bonds (debt) at a low rate (call it 3%) to raise money and then they can buy back their stock in the open market using those funds. By buying the stock back, the company is increasing investor returns as well.

- Quote (P. 167): “Over the past few years, quantitative easing has helped push longer-term interest rates to record lows. Corporations have taken advantage of the record low interest rates and issued record amounts of debt that they used to buy back stock. A notable example of this is Apple, which bought back around 20% of its shares between 2015 and 2019. Even though the company’s net income in 2019 was around the same level as in 2015, its earnings per share had materially risen due to the smaller number of shares outstanding. This financial engineering helped Apple’s share prices double over that 4-year period.”

- Agency Mortgage-Backed Securities — Agency MBS are mortgage-backed securities fully backed by the government. These are bonds that receive the cash flow generated by a pool of mortgage loans. The government can either guarantee the mortgage-backed securities or the mortgage loans underlying those securities. Agency MBS are the second largest market for bonds in the U.S. with over $8.5 trillion outstanding. The vast majority of Agency MBS are backed by single family home mortgages.

- Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac — Fannie and Freddie are the two giants of the mortgage bond market. Their job is to support the U.S. housing market by providing liquidity in the secondary mortgage market. They do this by buying mortgage loans and packaging them into securities that can be sold to investors. The loans underlying the securities are guaranteed by Fannie and Freddie, so investors don’t have to worry about any homeowner defaulting.

- 2008 Financial Crisis — Historically, mortgages were originated by commercial banks who held on to the mortgage loans for interest income. Fannie and Freddie offer commercial banks the additional option of selling the mortgage loan. This additional flexibility was designed to encourage commercial banks to make more mortgage loans since they always had the option of selling them to Fannie or Freddie in case they needed to raise money. This also, unfortunately, contributed to the 2008 financial crisis because banks were focused on lending to anybody that wanted a loan so they could package the mortgage and sell it to Fannie and Freddie. Those bad borrowers later defaulted on their loans en mass and led to a housing, banking, and stock market crash that crushed the economy.

- Treasury Securities — Treasury securities are the deepest and most liquid market in the world and the bedrock of the global financial system. Almost all U.S. dollar assets are priced off of Treasury yields, which are considered the risk-free benchmark. While retail investors hold bank deposits as money, institutional investors throughout the world hold Treasuries as money. Treasuries are issued by the U.S. government in regular auctions in a range of maturity dates, broadly divided into bills and coupons. With over $7 million of Treasuries held by foreigners, people from other countries supply a ton of U.S. debt, led by China and Japan.

- T-Bills — Treasury bills are short-term instruments debt that mature within 1 year and are issued at a discount, while coupons are issued on Treasury securities that have maturity dates in the range of 2-30 years. T-Bills are were many large investors, institutions, and countries (e.g. China) park huge amounts of money. This is because T-Bills are basically money that pays interest and is very safe as it is guaranteed by the U.S. government.

- Treasuries, Quantitative Easing, and the Fed — Nobody has bought more Treasuries since 2008 than the Fed. As discussed earlier in the book, the Fed buys Treasuries as part of its quantitative easing program. When the Fed buys Treasuries, it drives up the market price for these Treasuries, which in turn lowers the yield offered by the Treasuries. Because Treasuries are the standard that all other investments are compared to, when Treasuries are offering low interest rates, all other interest rates in the market must be lowered in response. These low interest rates lead to more people taking out loans and spending money in the economy. Also, by buying Treasuries from banks, the Fed is forcing the banks to take on more money in reserves in exchange, which encourages banks to lower interest rates so they can attract borrowers and lend the money out.

- Chapter Takeaway — Capital markets include both equity and debt. Equity is ownership interest in a company and includes public and private equity. Debt is issued by the government and corporations. The debt market is far bigger than the equity market. The Fed controls interest rates by buying and selling Treasury securities.

Ch. 8: Crisis Monetary Policy

- Crisis Management — One of the Fed’s big responsibilities in addition to monetary policy is to helps stop a crisis. The Fed does this by being a “lender of last resort.” Through its ‘discount window’, the Fed is able to lend money to banks in an emergency where the bank is on the brink of failing.

Ch. 9: How to Fed Watch

- Transparency — Everything the Fed does and says has huge impact on the stock market and economy. As a result, it doesn’t like to surprise the market. Through its various communications, the Fed does a good job of providing transparency so investors and market participants have an understanding of why it is doing. A few of the ways the Fed communicates, ranked in order of importance, includes:

- FOMC Statement

- FOMC Press Conference

- FOMC Minutes

- FOMC Dot Plot

- Fed Official Speeches

- Fed Interviews

- Desk Operating Statements

- Fed Balance Sheet

- Fed Surveys

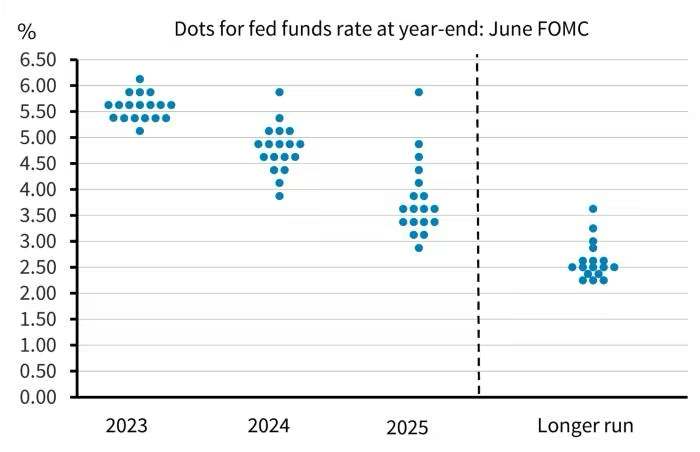

- FOMC Dot Plot — In 2012, the Fed began creating and publishing a “dot plot” to show where each Fed member projected the federal funds rate to be at the end of a certain year. The dot plot is very important and widely tracked because it gives insight into what the various Fed members are thinking regarding interest rates. This thinking is likely to influence the Fed’s monetary policy decisions in the future, which is why it’s an important document. The more consensus there is in the dot plot, the more strongly the market will price in upcoming Fed actions. For example, if most of the dots are around 3%, the majority of Fed members believe federal funds rates (and therefore interest rates) will be around 3% at the end of the specified year. It’s almost like a survey of Fed members.