100 Ways to Improve Your Writing

Gary Provost

GENRE: Business & Finance

GENRE: Business & Finance

PAGES: 176

PAGES: 176

COMPLETED: August 13, 2024

COMPLETED: August 13, 2024

RATING:

RATING:

Short Summary

Writing is hard. In 100 Ways to Improve Your Writing, renowned author Gary Provost offers valuable tips, tricks, and advice to help readers become polished writers.

Key Takeaways

Favorite Quote

“Do not write until you know why you are writing. What are your goals? Are you trying to make readers laugh? Are you trying to persuade them to buy a product? Are you trying to advise them? Are you trying to inform them so that they can make a decision? If you cannot answer the question ‘Why am I writing this?’ then you cannot wisely choose words, provide facts, include or exclude humor. You must know what job you want done before you can pick the tools to do it.”

Book Notes

Ch. 1: Nine Ways to Improve Your Writing When You're Not Writing

- Read! — One of the best ways to improve your writing is to read anything and everything you can get your hands on. Not only will the examples you take in help you pick up on how to use punctuation and write with correct grammar, but you will also learn the strategy behind persuasive and informative writing. You can multiply the benefit by reading books and articles that pertain to your job or the industry you work in. Reading this kind of material will expose you to the unique vocabulary, jargon, and terminology that people in your line of work like to use. Overall, reading is one of the very best ways you can improve your writing. Stephen King, a legendary writer in his own right, also praises the virtues of reading.

- Research — No matter what your assignment is, writing is a lot easier when you have done your research. Having lots of facts, stories, and data points to draw on will give you plenty of ammo to work with as you write. When you know your subject or topic like the back of your hand, all kinds of leads and angles will pour into your mind. This is a critical part of the writing process; make sure you do a great job of studying your subject. If you find yourself struggling to fill the page, you may need to go back and do more research.

- Quote (P. 12): “You cannot write securely on any subject unless you have gathered far more information than you will use.”

- Quote (P. 24): “Gather much more material than you will use. Just as high water pressure makes more water flow faster, the greater weight of material you have gathered will make the words flow faster.”

- Write In Your Head — A great way to get your writing project started (which is always difficult) or overcome periods of writer’s block is to “write in your head.” This involves thinking through the lead, structure, angles, and overall approach that you want to take to your project. This should be done away from the computer: In the car, in the shower, on the commute to work, while eating lunch. Writing in your head will help you get off to a good start when you do eventually sit down to work on your project.

- Quote (P. 14): “So if you have a writing job, write in your head. Clear up the inconsistencies while you’re brushing your teeth. Get your thoughts organized while you’re driving to work. Think of a slant during lunch. And most important, come up with a beginning, a lead, so that you won’t end up staring at your typewriter as if it had just arrived from another galaxy. If you have spent time writing in your head, you’ll have a head start. The writing will come easier, and you’ll finish sooner.”

- Chapter Takeaway — Read as much as you can. In addition to learning about subjects, you’ll train yourself to write better.

Ch. 2: Nine Ways to Overcome Writer's Block

- Outlines & Lists — Research isn’t the only element of a good pre-writing process. You should also create an outline, even if it’s only a short list of items you want to touch on. An outline will make your writing sessions easier by keeping you on track and giving you topics to hit as you go so you don’t have to continuously think about what to tackle next. I like lists. Long, complicated outlines can be confusing. I prefer to create a list of items I want to write about and organize them in a sequential order.

- Quote (P. 23): “But you should organize the material. Organizing will help lock in the logic of what you say, and it will speed the writing process.”

- Quote (P. 24): “But an outline is just a list of elements you want to put into your writing, and for any story or article you should make some sort of list, even if it’s just three words scribbled on a scrap of paper. Write some key words for the issues you want to cover, the facts you want to point to, the questions you want to pose. Glance at the list as you work. This will help you decide what to write next.”

- Know Your Audience — It is critical that you have a firm understanding of who you are writing to. Who is the intended reader? What is he like? What motivates him? What are his pain points? These are important questions. Not having a clear understanding of your intended reader will lead to content that misses the mark. Knowing your reader, and knowing the ‘why’ behind the piece (more on this in the next bullet), will dictate everything you do as you write.

- Know Your Why! — This may be the most important takeaway from this book, and it closely aligns with tips I’ve read in several other copywriting books. Every writing project MUST have a clear, well-defined purpose. WHY are you writing this? What is the goal? What are you trying to get the reader to do? These questions must be answered in a one or two sentence statement that will serve as the credo for the entire piece. Why is this so important? The purpose of the project will direct literally every piece of the content. Word choice, sentence structure, the call to action, the hook, the headline, quotes and testimonials, data points, the overall layout — all of these will be directly influenced by the purpose of the piece. Again, the purpose (the why) MUST be clearly defined. Once it is, put it at the top of the document and allow it to guide you as you write.

- Quote (P. 26): “Do not write until you know why you are writing. What are your goals? Are you trying to make readers laugh? Are you trying to persuade them to buy a product? Are you trying to advise them? Are you trying to inform them so that they can make a decision? If you cannot answer the question ‘Why am I writing this?’ then you cannot wisely choose words, provide facts, include or exclude humor. You must know what job you want done before you can pick the tools to do it.”

- Chapter Takeaway — Know your why! Take the time to craft a one or two sentence purpose statement for the writing project. This statement will serve as your guiding light and dictate everything you write. Put this purpose statement at the top of the document and refer to it often.

Ch. 3: Five Ways to Write a Strong Beginning

- Find an Angle — Finding an “angle” is one of the keys to effective copywriting. There needs to be one, and only one, central message that you’re trying to communicate. This is your “angle.” What point are you trying to make? What are you really trying to say about the topic? These are angles, and they are important for all of your writing projects, no longer how long or short. Without an angle, you will have a hard time writing anything. Typically the angle ties into your purpose statement for the project (discussed in the previous chapter).

- Quote (P. 31): “Do not try to write everything about your subject . . . Tie yourself to a specific idea about your subject, some aspect that is manageable. That aspect is called the angle.”

- Write a Strong Lead — In today’s distracted world, you have to get somebody’s attention very quickly if you have any shot of getting them to read. This goes for all forms of copy, whether it’s an article or a social media post. It’s true for email, too. The way to do this is with your headlines and the first few sentences of your copy. These need to be electric. They should be snappy, visual — and, above all, they should create curiosity in the reader. Curiosity is what gets the reader to continue down your “slippery slide.” There are a few strategies for writing strong leads. The commonality between all of them is curiosity — they all capture and hold attention using curiosity.

- Something to Care About — People care about themselves, first and foremost. If you give the reader information that affects him directly, you will get his attention right away. This is especially powerful when writing emails. The key with this one is not to wait. Get right to the point — pack that valuable information in the first sentence or two. This will get the reader to read on: Wait, this affects me HOW?! This can help me HOW?! As other copywriting books have also pointed out, people don’t care about you or your company. They care about themselves. How will what you’re saying affect the reader? How will it help him? These are the points that matter. Do not waste time talking about yourself.

- Tell a Story — Humans are programmed to enjoy stories. Tell a story in your first paragraph to draw the audience in and set up the rest of the copy. The story should have some kind of relevance to the key point (“angle”) that you’re trying to hit. Bonus points if the story is somehow relatable to the audience. When a reader can relate to the story, or person in your story, they enjoy it more.

- Ask Questions — Questions are irresistible. When’s the last time you saw a question and didn’t feel an urge to answer it? Exactly. Pose a question early in the copy to get the reader engaged. Continue to ask questions throughout the copy.

- Dynamic First Sentence — Your very first sentence should be short and dynamic. Short to help the reader build some momentum. Dynamic because it needs to get the reader’s attention.

- Bold Statement & Interesting Facts— Blitzing the reader right away with a bold statement will grab his attention. Similarly, you can use interesting facts to draw readers in and create curiosity.

- Good Rhythm — Vary your sentence length. Short. Medium. Long. This makes for a much more pleasant and enjoyable reading experience. It also allows the reader to continue to build momentum as they go.

- Vivid Mental Images — A strong lead will often place in the mind of the reader a vivid image. Paint a picture with your words. Use electric language. Use “like X” and “as X as X” and “as if X” to make connections and create your image. Try to make the reader “see” what you’re saying.

- Quote (P. 33): “A lead should be provocative. It should have energy, excitement, an implicit promise that something is going to happen or that some interesting information will be revealed. It should create curiosity, get the reader asking questions.”

- Quote (P. 33): “Your lead should give readers something to care about before it gives them dry background information. ‘Something to care about’ usually means one of two things. Either you give the readers information which affects them directly, or you give them a human being with whom they can identify.”

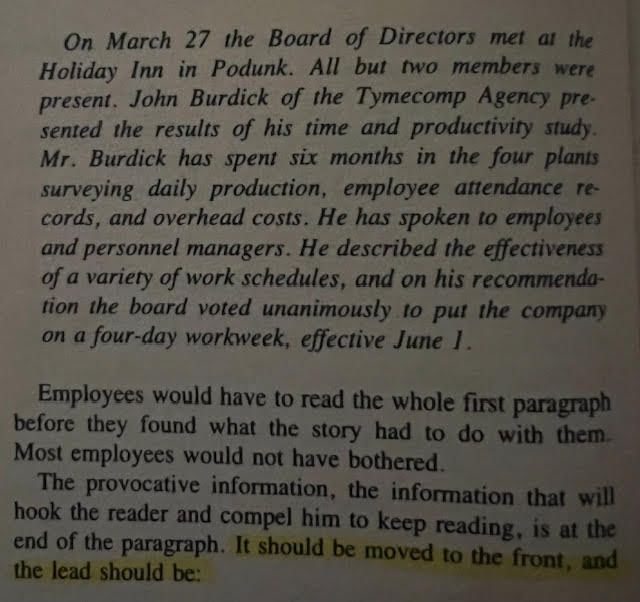

- Don’t Beat Around the Bush — Some writers take paragraphs and pages to get to their point. Don’t do this. Get to your point quickly. Be direct. Cut any information that isn’t serving a purpose. Same with your sentences — cut words that aren’t serving a purpose. Trim the fat. Don’t waste words. Structurally, the information that directly affects the reader should be toward the very front. Don’t beat around the bush, and don’t bury the lead. The photo below has a good example and explanation of this concept.

- Ex. Bad — I’m writing this memo because Sam Moroni has fled the country, and I need to replace him quickly.

- Ex. Good — Sam Moroni has fled the country, and I need to replace him quickly.

- Quote (P. 152): “Every word you write should be doing some work in the sentence. It should earn its keep by providing some portion of the total information you are trying to communicate. A word is unnecessary if it’s doing no work, if it’s doing work that doesn’t have to be done, or if it’s doing work that’s being done by another word or phrase nearby. Read what you have written and cross out every word that is not contributing information.”

- Chapter Takeaway — Learn how to write strong leads! These will help you get the reader’s attention, increasing the chances that your copy will be consumed.

Ch. 4: Nine Ways to Save Time and Energy

- Use Topic Sentences — A topic sentence acts sort of like a lead for every paragraph. It is usually the first sentence of the paragraph. It presents one idea or “angle,” and the rest of the paragraph is dedicated to supporting the statement. Topic sentences therefore help organize your thoughts and writing. If you can churn out a topic sentence, you will be well on your way to a strong paragraph.

- Quote (P. 44): “A topic sentence in a paragraph is a sentence containing the thought that is developed throughout the rest of the paragraph. The topic sentence is commonly the first sentence in a paragraph. Deciding what to put in a paragraph and what to leave out will be easier if you first write a topic sentence. For each paragraph ask, ‘What do I want to say here? What point do I want to make? What question do I want to present?’ Answer with a single general sentence. That is your topic sentence.”

- Keep Paragraphs Short — Throughout your copy, you have to be mindful of the reader’s patience and attention, and you should do everything possible to make things easy for them. One of the ways to accomplish this is by keeping your paragraphs short. Short paragraphs are easy on the eyes. They give the reader a break. They keep thoughts ordered and organized. The last thing you want to do is write paragraphs that are wordy and drawn-out.

- Don’t Explain When You Don’t Need To — I have a bad habit of this. If an explanation isn’t absolutely needed, don’t provide one. Not everything needs an explanation. If the point you’re making in an email, for example, isn’t critical, don’t feel the need to explain it. On the other hand, if what you’re referring to is of major importance, dive into the details. This goes back to the point about reducing wordiness.

- Be Direct — This is an area where I feel my writing could improve. I have a tendency to get wordy and over-explain things with filler words — words that don’t serve much of a purpose. I also tend to write with a passive voice. Focus on being direct by writing with more of an active voice (vs. passive voice). The active voice is more commanding. As you review your work, shave off words that simply float around and don’t seem to contribute to what you’re saying. Try to make your point in as few of words as possible.

- Ex. Bad — In preparing a list of professional people whose opinion I respect, you are one of the first that comes to mind. It is my objective to more fully utilize my management expertise than has heretofore been the case . . .

- Ex. Good — I’ve made a list of professional people whose opinion I respect, and your name is at the top of the list. I want to use my management skills more fully. But since I’ve been running a small apartment management agency for the last six years, I’m a little bit out of touch with the job market. I’d like your guidance and advice so that I can evaluate the market for my skills.

- Steal — It’s ok to steal content and inspiration that can help you with your writing project! Other copywriting books have echoed the same thought. Always be on the hunt for great writing, and don’t be afraid to mimic the style of an author you admire. This also goes for stealing stories and using them in your lead. The key takeaway here: always keep your eyes and ears open for inspiration that can enhance your writing.

- Quote (P. 51): “Be a literary pack rat. Brighten up your story with a metaphor you read in the Sunday paper. Make a point with an anecdote you heard at the barber shop. Let a character tell a joke you heard in a bar. But steal small, not big, and don’t steal from just one source. Someone once said that if you steal from one writer, it’s called plagiarism, but if you steal from several, it’s called research. So steal from everybody, but steal only a sentence or a phrase at a time.”

- Chapter Takeaway — My tendency is to write with a passive voice. Try writing with more of a commanding, active voice. And use topic sentences to help you write each of your paragraphs.

Ch. 5: Ten Ways to Develop Style

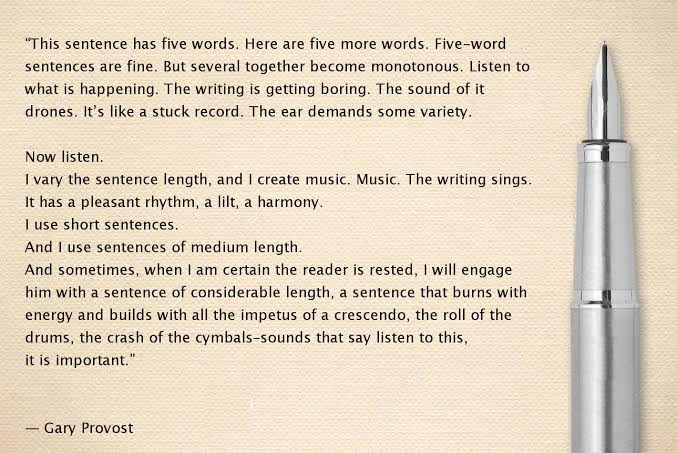

- Create Rhythm: Vary Sentence Length — This is another one of the big takeaways from this book. Varying your sentence length creates great rhythm in your writing. And rhythm significantly enhances the reading experience. Nobody likes to read a bunch of long sentences. Nobody. At the same time, nobody wants to read short sentences over and over. Be conscious of the length of your sentences, and mix them up as you go. Your reader will be very happy about it. You’ll help them build reading momentum, and the experience will be much more enjoyable overall. See the graphic below for an example and explanation from the author.

- Show, Don’t Tell — We are visual creatures. We like to be able to see things; it helps us better connect with and understand information. This is why video is the most popular and effective communication medium. This is also why, whenever possible, you need to try to create with your writing vivid mental images in the reader’s head. Use words to show the reader what you’re trying to say. Don’t tell them. Show them. Paint the picture. Set the scene. By using words to plant images in your reader’s mind, you will bring the information to life. The reader will enjoy the experience much more than if you simply talk at them (tell them). A few examples:

- Ex. Bad — Dear Jan, my new boyfriend, Arnold, is a terrific athlete. He is also incredibly smart, very sentimental, and sort of strange.

- Ex. Good — Dear Jan, my new boyfriend, Arnold, ran five miles to my cabin in the middle of that lightning storm last week. When he got here, he stood out in the rain and started shouting how he loves me in five different languages.

- Ex. Bad — Ms. Resnikoff has been loyal, hardworking, and helpful to the company. I think she deserves a promotion.

- Ex. Good — Ms. Resnikoff turned down two offers from Westinghouse last year. She worked fourteen-hour weekends, and she saved the Renaldo account even after it was discovered that the rabbit warehouse was empty. She deserves a promotion.

- Chapter Takeaway — Vary your sentence length to create rhythm in your writing. The author does this very well throughout the book. When appropriate, use your words to paint a picture in the mind of your reader. Humans are visual creatures; creating mental images with your words will allow the reader to better connect with what you’re trying to communicate.

Ch. 6: Twelve Ways to Give Your Words Power

- Use Short Words — Short words are generally better than long words. Stop is stronger than discontinue. And rape is more powerful than sexual assault. Try to stick with shorter words — they click with the reader and are easier to absorb. Similarly, avoid using unfamiliar words. It’s fun to show off your vocabulary, but your fancy words lack power because your audience won’t know what they mean. Generally speaking, short words are words most people know.

- Quote (P. 73): “Short words tend to be more powerful and less pretentious than longer words.”

- Quote (P. 74): “Familiar words have power. By avoiding very long words, you avoid most of the words that your reader doesn’t know.”

- Use Dense Words — Use dense words. These are words that can communicate what you want to say in one word rather than several. Impossible to imagine is inconceivable; something new is novel; people they didn’t know are strangers. The editing process is where you can make good use of this tip. As you review your work, inspect your sentences and look for areas where you can replace two or three words with one dense word. In general, the fewer words you use to communicate an idea, the more impact you will have. Using dense words is one of the ways you can reduce the number of words you use.

- Quote (P. 74): “A dense word is a word that crowds a lot of meaning into a small space. The fewer words you use to express an idea, the more impact that idea will have. When you revise, look for opportunities to cross out several words and insert one.”

- Use Active Verbs — This is a really good tip. Verbs are the engine of your writing. Active verbs are verbs that do something. They communicate action and motion. Inactive verbs are verbs that simply are something. These are verbs of being like is, was, will be, etc. Pay close attention to your verb selection. By choosing active verbs, you can electrify your writing and create vivid images in your reader’s mind. This is once again a great technique to implement into your editing process; go through your copy and look for passive, weak verbs. Replace these verbs with strong, active verbs. This will bring your writing to life.

- Quote (P. 75): “Active verbs do something. Inactive verbs are something. You will gain power over readers if you change verbs of being such as is, was, and will be to verbs of motion and action.”

- Ex. Bad — A grandfather clock was in one corner, and three books were on top of it. As Samson enters the police station, a burly sergeant is behind the desk, and three rookies are around the corner talking shop, ignoring the murder suspect who is near the open window at the back of the room.

- Ex. Good — A grandfather clock towered in one corner, and three books lay on top of it. As Samson enters the police station, a burly sergeant stands behind the front desk, and three rookies hang around the water cooler talking shop, ignoring the murder suspect who edges near the open window at the back of the room.

- Use Strong Verbs — Similar to the previous point, use strong, precise active verbs. Again, verbs are the engine of your writing. Simply by taking the time to choose great verbs that communicate action and motion, you can inject a lot of life into your writing. To help with this, focus on choosing very precise verbs: turn look into stare, peek, gaze, or gawk; turn throw into toss, flip, or hurl. Doing this will also help you eliminate adverbs, which are basically just adjectives with “-ly” at the end that attempt to strengthen the weak verb you are really trying to use. Adverbs are terrible and should be avoided. Stephen King agrees with this. When you choose strong verbs, you eliminate the need for adverbs. The key point here: go back and look at all of your verbs. Look for opportunities to replace weak verbs with strong ones.

- Quote (P. 76): “Verbs, words of action, are the primary source of energy in your sentences. They are the executives; they should be in charge.”

- Quote (P. 76): “If you choose strong verbs and choose them wisely, they will work harder for you than any other part of speech. Strong verbs will reduce the number of words in your sentences by eliminating many adverbs. And, more important, strong verbs will pack your paragraphs with the energy, the excitement, and the sense of motion that readers crave. Sharpen a verb’s meaning by being precise.“

- Quote (P. 76): “Inspect adverbs carefully and always be suspicious. What are those little buggers up to? Are they trying to cover up for a lazy verb? Most adverbs are just adjectives with “-ly” tacked on the end and the majority of them should be shoveled into a truck and hauled off to the junkyard.”

- Ex. Bad — I stood on the stairs and watched as he got back a bit and forcefully pushed his foot against the door. The door opened up with a screechy metallic sound. Currie went inside. I went quickly down to the doorway to see what would happen. The old lady was on the other side of her kitchen dialing the phone and staring angrily into the air. She pointed the phone receiver at Currie, as if she could shoot him with it.

- Ex. Good — I stood on the stairs and watched as he reared back and slammed his foot against the door. The door flew open with the screech of wrenching metal hinges. Currie rushed inside. I ran down to the doorway to see what would happen. The old lady was on the other side of her kitchen dialing the phone and scowling at the air. She aimed the phone receiver at Currie, as if she could shoot him with it.

- Use Specific Nouns — The overall point about being precise with your word selection continues with your noun selection. Just like with your verbs, you want to be conscious of the nouns you’re using. Specific nouns have power. By using specific, dense nouns, you help your reader “see” what you’re trying to say. Did a man walk into the room, or did a priest walk into the room? A priest walking into the room is easier to see in the mind. Is it a large house, or does it qualify as a mansion? Is it a fast car, or a Jaguar? Is it a black dog, or a Doberman? Take every opportunity to use specific nouns; they help bring your writing to life. This is another good tip to incorporate into your editing process.

- Quote (P. 78): “Good writing requires the use of strong nouns. A strong noun is one that is precise and densely packed with information.”

- Quote (P. 79): “When you take out a general word and put in a specific one, you usually improve your writing.”

- Use the Active Voice — You should aim to use the active voice (Subject → Verb → Object) the majority of the time. Compared to the passive voice (Object → Verb → (by Subject), which tends to be weak, the active voice is more direct, uses fewer words, and generally keeps the reader more engaged. It’s a little confusing, but the best way I can describe the active voice is that it states that the subject of the sentence (i.e. person, place, etc.) did something vs. something happened to the subject. As a result, the active voice tends to avoid passive words like was, were, etc. when describing events. A few examples:

- Ex. Passive — Dutch drawings and prints are what this book is about

- Ex. Active — This book is about Dutch drawings and prints

- Ex. Passive — The light bulb was screwed in crookedly by the electrician

- Ex. Active — The electrician screwed in the light bulb crookedly

- Quote (P. 80): “Generally the active voice makes for more interesting reading, and it is the active voice that you should cultivate as your normal writing habit.”

- Use Positive Language — Try to use positive language most of the time. By “positive language,” we’re talking about describing what did happen vs. what didn’t happen, or what is going on vs. what isn’t going on. “Negative language” is used when you describe what didn’t happen. Again, positive language is describing the actual outcome of a situation. It’s more direct, whereas negative language is sort of beating around the bush of what actually happened. Examples will provide the best explanation:

- Ex. Negative — The safe was not closed

- Ex. Positive — The safe was open

- Ex. Negative — Ronaldo’s plan to breed giant rabbits did not succeed

- Ex. Positive — Ronaldo’s plan to breed giant rabbits failed

- Ex. Negative — Martha was not sober when she arrived home

- Ex. Positive — Martha was drunk when she arrived home

- Quote (P. 82): “Usually what matters is what did happen, what does exist, and who is involved [in the situation]. So develop the habit of stating information in a positive manner.”

- Use Negative Language — Although you primarily want to stick with positive language when writing, there are instances where the ambiguity of negative language is more appropriate. Again, negative language kind of beats around the bush and describes what didn’t happen vs. what did happen. The example below provides a nice example where the negative language is more appropriate:

- Ex. Negative — Russian athletes did not come to the LA Olympics

- Ex. Positive — Russian athletes were in Russia during the LA Olympics

- Be Specific — The theme of this chapter is to be specific with your word choice, with an emphasis on verbs and nouns. Really, though, this rule goes for all of your words. The more descriptive you can be, the more clearly your reader will see in his mind what you are trying to communicate. There’s obviously a limit to this, but use as much detail as you can when describing things. Try to avoid being overly general and wide-sweeping.

- Ex. Bad — He drives a fast truck

- Ex. Good — He drives a Tesla Cybertruck

- Ex. Bad — Recently, there was a death in my family

- Ex. Good — My aunt died on March 5

- Ex. Bad — My son James is having a tough time with two subjects

- Ex. Good — My son James is flunking science and math

- Use Statistics & Facts — Writers need to back up their claims. This is where statistics and data are clutch. By using statistics to support your writing, you both prove what you’re stating and establish credibility with the reader. The key here is to avoid overloading your writing with a bunch of data points. Pick your spots. Statistics should be sprinkled like pepper, not smeared like butter. When it comes to the use of facts, you want to use these to build your whatever case you’re presenting. Don’t just blast your own conclusion and opinion in the reader’s face. Present the facts in a way that will guide the reader toward the conclusion you want him to reach.

- Emphatic Words Go Last — The words you most want to communicate should be placed at the end of a sentence. People tend to remember the last bit of your message or sentence. This seems like a great tip for email correspondence. For example, if you are sending something to an executive for review and want to emphasize a deadline, write: Please review this report by the submission deadline on June 6. What you don’t want to do is this: The submission deadline is coming up on June 6, please review the report and let me know your thoughts. The due date is what you’re trying to emphasize; by putting it toward the front of the sentence, you risk having it float right through the reader’s mind.

- Quote (P. 87): “Emphatic words are those words you want the reader to pay special attention to. They contain the information you are most anxious to communicate. You can acquire that extra attention for those words by placing them at the end of the sentence.”

- Quote (P. 87): “This is a lesson best learned by ear. Listen to how the impact of a sentence moves to whatever information happens to be at the end.”

- Chapter Takeaway — Word selection is critical. It’s how you create vivid mental images in your reader’s head. By selecting very specific verbs and nouns, you can bring your writing to life. The best way to approach word selection is to incorporate it into your editing process. Go through your copy and replace weak verbs and nouns with stronger, more specific ones. Pick ones that are active and actionable. Doing this will ignite your sentences and likely help you reduce the number of words you’re using.

Ch. 7: Eleven Ways to Make People Like What You Write

- Connect With Your Reader — The odds of your reader doing what you want him to do go up when he likes you. Therefore, you need to find a way to connect with your reader. Pinpointing a common enemy (i.e. a pain point) and placing yourself on the reader’s side is one way to do this. Show the reader how your product will help them overcome the pain point. Being vulnerable (e.g. admitting mistakes, sharing a personal story, etc.) is another way. Highlighting commonalities between you and the reader is also a good strategy (people like people who are similar to them). Humor is yet another strategy. It’s all about connecting with the reader on a human level.

- Quote (P. 91): “Readers will like you if you seem to understand who they are and what their world is like.”

- Quote (P. 92): “Readers will like you if you show that you are human.”

- Write About People — People find other people fascinating. Try to incorporate people into anything you write. This applies even if you’re writing about a product. Don’t simply write about the product’s features. You will bore people to death if you do that. Instead, write about the product’s features in a way that shows how the reader stands to gain from acquiring these products. Write about how the product is going to help them accomplish their goals. Another example: if you’re writing a brochure to attract new members to your church, write about the people who attend the church regularly. Don’t write about the steeple and organ.

- Quote (P. 92): “People is the one subject that everybody cares about. What do other people think? How do they act? What makes them angry, happy, enthusiastic? How will they vote in the next election? How can I get them to fall in love with me, buy my product, support my plan? These are the questions readers ask.”

- Quote (P. 93): “Don’t write about the new bookkeeping system. Write about how the new bookkeeping system will affect people.”

- State Your Opinion — This is not always possible to do as a copywriter in a corporate setting. But whenever possible, try to incorporate your opinion into your writing. By doing so, you give the reader something to think about, whether or not they agree with your view on things. And when you get the reader thinking and talking to others, your writing has been successful. Writing that lacks an opinion is generally a bit boring. There’s simply not as much substance there, and that’s not always a bad thing in a setting like the corporate environment where you represent a company. But giving an opinion certainly does liven things up.

- Use Anecdotes — An anecdote is a little story or incident that makes a point about your subject. These are a terrific way to start an article or almost any kind of writing project (I recently used an anecdote to begin our Collaborative Success content piece at Cambridge, and I used anecdotes all the time at the newspaper). Anecdotes are usually very interesting and help hook the reader right off the bat. You can also use anecdotes in the body of your project to keep your reader engaged and entertained. Ideally, your anecdote should make the point that you’re trying to get across. It should support the overall claim you’re trying to make in the piece.

- Quote (P. 96): “Anecdotes are great reader pleasers. They are written like fiction, often contain dialogue, and reduce a large issue to a comprehensible size by making it personal. Anecdotes crystallize a general idea in a specific way.”

- Quote (P. 96): “Writing a short, colorful anecdote is one of the most compelling ways to begin an article, query letter, or business proposal, and a couple of well-placed anecdotes in your longer stories will break the lock of formality and win your reader’s affection as well as his or her attention.”

- Use Examples — When it comes to offering value to the reader, examples pack a punch. Examples help clarify and cement what you’re trying to say. As an avid reader, I can attest to the power of examples. They are delightful and welcomed. But why? Sometimes it can be difficult to understand what the writer is getting at; examples help clarify the point in a short, concise way. As a reader, I’m always relieved when the author offers an example after explaining a difficult concept.

- Quote (P. 97): “They [examples] do a lot of work, and they impress readers. Examples are used to back up your statements. They clarify your generalizations and help to prove that you are right. Finally, they show the reader what, exactly, it is that you’re talking about.”

- Use Quotes — Quotes, whether from Muhammad Ali or the farmer you interviewed for your story, are a great way to support your claim. They should be used sparingly and strategically. In addition to supporting your points, quotes are always a welcomed sight for readers. They help break up the writing and offer a little bit of entertainment value. In general, they make the copy less intimidating for the reader. Bonus points if your quote is from a highly credible source (e.g. an expert in the field you’re writing about).

- Nail Your Headline — The headline and lead are arguably the two most important features of any writing project. These need to be strong in order to hook the reader. Good headlines convey information about the article in a way that is attention-grabbing and makes the reader curious. This often means they are bold or provocative. A few examples:

- Ex. Bad — Investigative Techniques and Conclusions Concerning the Proposal to Extend Client Services

- Ex. Good — Results of the Client Survey

- Ex. Bad — How Sports Enriched my Religious Life

- Ex. Good — A Christian Looks at Baseball

- Ex. Bad — Tips on an Important Purchase

- Ex. Good — Six Ways to Save Money Buying a House

- Chapter Takeaway — There’s a lot you can do to spice up your writing. Mix in quotes, anecdotes, examples, etc. These complimentary pieces not only support the overall point you’re trying to make, but they also provide a bit of entertainment value for the reader. They make the reading experience more enjoyable. Sprinkle these in across all of your writing projects.

Ch. 8: Ten Ways to Avoid Grammatical Errors

- Respect the Rules of Grammar — Grammar is a lost art today. It’s important to have a strong command of grammatical rules so you can come across to the reader as competent. You lose the reader’s respect the second you write something like the company lost it’s way rather than the company lost its way. Below are a few rules to keep in mind:

- Don’t Change Tenses — Once you’ve established a tense (e.g. past, present, future), stick with it throughout the sentence or statement. Don’t switch up your tense mid-sentence. Be consistent.

- Ex. Bad — We were going over to Tad’s house to see his daughter, Riley. When we arrived, Molly says, “The baby just fell asleep, so you can’t see her.”

- Ex. Good — We were going over to Tad’s house to see his daughter, Riley. When we arrived, Molly said, “The baby just fell asleep, so you can’t see her.”

- Ex. Bad — You have been late for work; your work is of poor quality; and you don’t seem to care about this company.

- Ex. Good — You are late for work; your work is of poor quality; and you don’t seem to care about the company.

- Avoid Splitting Infinitives — Try not to break up an infinitive (i.e. the “to-verb” sequence). Sometimes you will have to, but try to avoid it.

- Ex. Bad — She wanted to quickly run the race

- Ex. Good — She wanted to run the race quickly

- Ex. Bad — Dave wanted to really make it big as a singer

- Ex. Good — Dave really wanted to make it big as a singer

- Ex. Bad — If we were to carefully examine the problem, we could figure out a solution

- Ex. Good — If we were to examine the problem carefully, we could figure out a solution

- Who vs. Whom — Many people cannot remember the difference between who and whom. (Who is nominative case, and whom is objective case, as in “Who is going to the prom with you, and with whom did she go last year?”)

- Lay vs. Lie — Almost everybody gets confused about lay and lie. (And with good reason. Lay means to put something down, and lie means to recline, but the past tense of lie is, would you believe, lay.)

- Don’t Change Tenses — Once you’ve established a tense (e.g. past, present, future), stick with it throughout the sentence or statement. Don’t switch up your tense mid-sentence. Be consistent.

- Chapter Takeaway — Strive for perfect grammar, but understand that it’s hard to follow every rule and it’s more important to write well. If your ideas are coming across clearly, it’s OK if you commit a few grammatical sins.

Ch. 9: Six Ways to Avoid Punctuation Errors

- Using Commas — Commas are tricky. They are used in a variety of situations, and it’s not always easy to tell when one is needed or not. In many cases, it feels like commas are used subjectively and at the writer’s discretion. A few tips I took away from this section regarding commas include the following:

- Restrictive and Unrestrictive Elements — Restrictive words and clauses must be part of the sentence in order for the sentence to retain its intended meaning. Sentences with restrictive elements do not need commas. Unrestrictive clauses and words can be removed from a sentence, and the sentence will still make sense. These unrestrictive elements do need commas. Take a look at the examples below. Notice that there are commas around nonrestrictive elements of a sentence. You could remove the words inside the commas and the sentence will still make perfect sense. This is why commas are needed.

- Ex. Restrictive — A dance like the limbo requires a broomstick or pole

- Ex. Unrestrictive — Some dances, like the limbo, require broomsticks and poles

- Ex. Restrictive — My friend Pat goes to law school

- Ex. Unrestrictive — One of my friends, Pat, goes to law school

- Introductory Words — Introductory words that start a sentence (e.g. Yes, No, But) need a comma. For example: Yes, I did take the money. It would be incorrect to write: Yes I did take the money. Another correct one: Now, if you take the bus, you’ll save money. The incorrect version would be: Now if you take the up bus, you’ll save money.

- Listen for Pauses — When deciding whether a sentence you have written needs a comma, read the sentence out loud. Is a pause needed for clarity? Read the sentence without the pause quickly, if you’re still not certain. If the sentence makes perfect sense to you read at breakneck speed, do not use a comma. Below is a tricky example. In this case, you need the pause in order to make it clear that she fainted. A comma is therefore used. If you read it out loud quickly, it becomes clear that a comma is needed. Another way to think of it: If you added a “she” in front of “fainted,” you would have two sentences that could stand on their own, which would require a comma. In this case the “she” is implied, even though it’s not there on paper. You can therefore safely add a comma.

- Ex. Incorrect — She was frightened when he kissed her and fainted.

- Ex. Correct — She was frightened when he kissed her, and fainted.

- Restrictive and Unrestrictive Elements — Restrictive words and clauses must be part of the sentence in order for the sentence to retain its intended meaning. Sentences with restrictive elements do not need commas. Unrestrictive clauses and words can be removed from a sentence, and the sentence will still make sense. These unrestrictive elements do need commas. Take a look at the examples below. Notice that there are commas around nonrestrictive elements of a sentence. You could remove the words inside the commas and the sentence will still make perfect sense. This is why commas are needed.